What is this mini-series about?

There are many great workshops on different aspects of adjudication in debating (e.g. the ones given by Olivia Sundberg, Yair Har-Oz, Daan Welling and Omer Nevo). However, I think one aspect of judging is neither very prominent nor very well-illustrated so far and that is probabilistic judging. The core thesis is that arguments are not just true or false, bought or not bought in their entirety, but they are “bought to some degree” or the judges are “convinced to some extend”, i.e. arguments are assigned probabilities or probability distributions. What I want to do in this mini-series are two things: a) Set up a basic framework of probabilistic judging and b) integrate and illustrate multiple facets of debating within that framework. This part deals with the evaluation of one argument in a vacuum, part II deals with direct interaction, i.e. rebuttal and extensions, and part III attempts to weigh arguments that are made along different metrics. To be very clear, I do NOT say that this is the ultimately correct way to judge a debate, I want to a) further the discourse on how arguments should be evaluated and b) illustrate how I think about probabilistic judging and give other people, who have thought less or different about the issue, a possibility to learn or improve their and my view.

I want to make this post as understandable as possible such that people who are very new to debating also get a chance to understand it. Given that I have a Machine Learning and Probability Theory background I might find concepts intuitive that you are new to. If such a situation occurs I would be grateful for feedback. If you, on the other hand, understand what I am saying but disagree with the content, I would also be interested in your criticism and possible solutions.

Motivation:

We don’t think about the world in a binary fashion. Our weather apps usually don’t say “It will rain” but “It will rain with a probability of 70 percent”. When we say something like “I am probably coming to the party” you express a probabilistic statement, i.e. you don’t say “I’m definitely coming” or “I’m definitely not coming” but rather “I am more likely to come than not”. Our decision making also works with probabilistic assessments. When the weather app says it will rain with 70 percent probability you might think: “well that is too much of a risk and I therefore do not go outside” or “I’m willing to take the risk”. These kind of assessments not only happen on a small level in our daily lives but also in the decision making of governments and companies. If the experts say there is a 5 percent chance of a nuclear attack on the country the government will not reply “We will just round this 5 percent to 0 percent and do nothing”. If a company predicts that there is a 40 percent probability that a part of their supply chain will fail, they will likely think of alternative strategies even though it is less likely to happen than not. The reason for these decisions is because the actors in question used an expected value, i.e. the probability of an event multiplied with its harm/benefit. The expected damage of a nuclear scenario with 5 percent is still very large and a scenario where your supply chains brake with 40 percent might have catastrophical results for the company.

But just assigning probabilities to an event does not tell the entire story, i.e. there can be a difference between two scenarios with the same assigned probability. We would, for example, say that around 50 percent of the outcomes of a repeated unbiased coin toss are tail and might also say that the probability of the stock market rising tomorrow is peaked around 0.5. The difference is in the uncertainty that we have about these numbers. While we are very confident that a number close to 50 percent is the correct one when it comes to coin tosses we were very uncertain about the actual state of the stock market. To include this estimate of uncertainty we can use probability distributions. To include this estimate of uncertainty we can use probability distributions. If that feels a bit overwhelming at first, I can totally understand. The basic message that I want to get out there is that the world is not binary, our decision making is not binary and therefore debating and adjudication should not be either - they should be probabilistic.

Part I: evaluating one argument

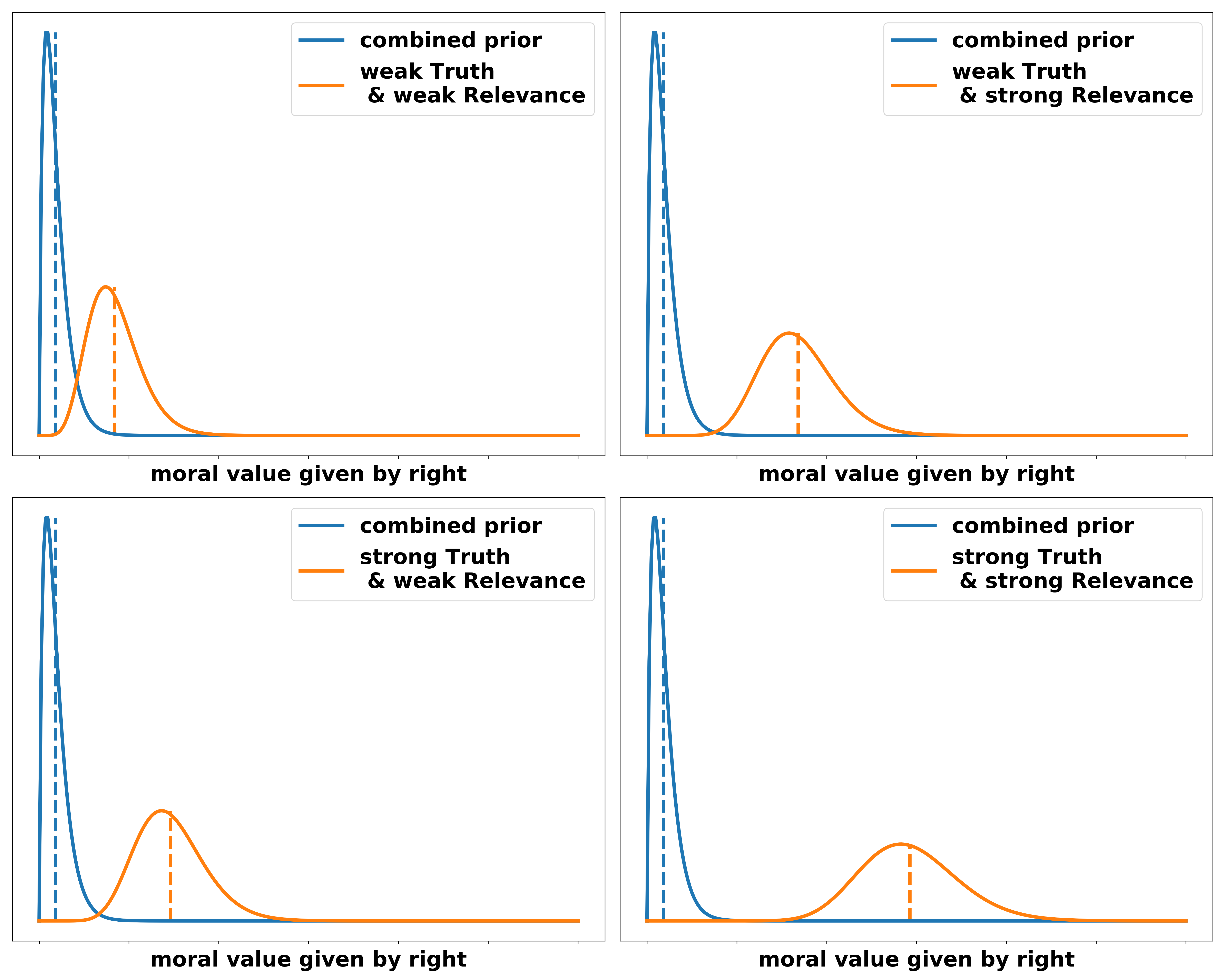

In this part I want to focus on evaluating one argument in a vacuum. That means we ignore most of the things happening in a usual debate. We ignore all other teams, all extensions, all rebuttal, all framings, etc. We only consider exactly one argument. The two necessary conditions for an argument to be persuasive are a) the argument is true and b) the argument is relevant. If you are convinced that an argument is true with high probability but not relevant you very likely do not care a lot about it. If you are convinced that something is important but not that it is true, you are not convinced by it either.

The fundamentals of Probabilistic Inference

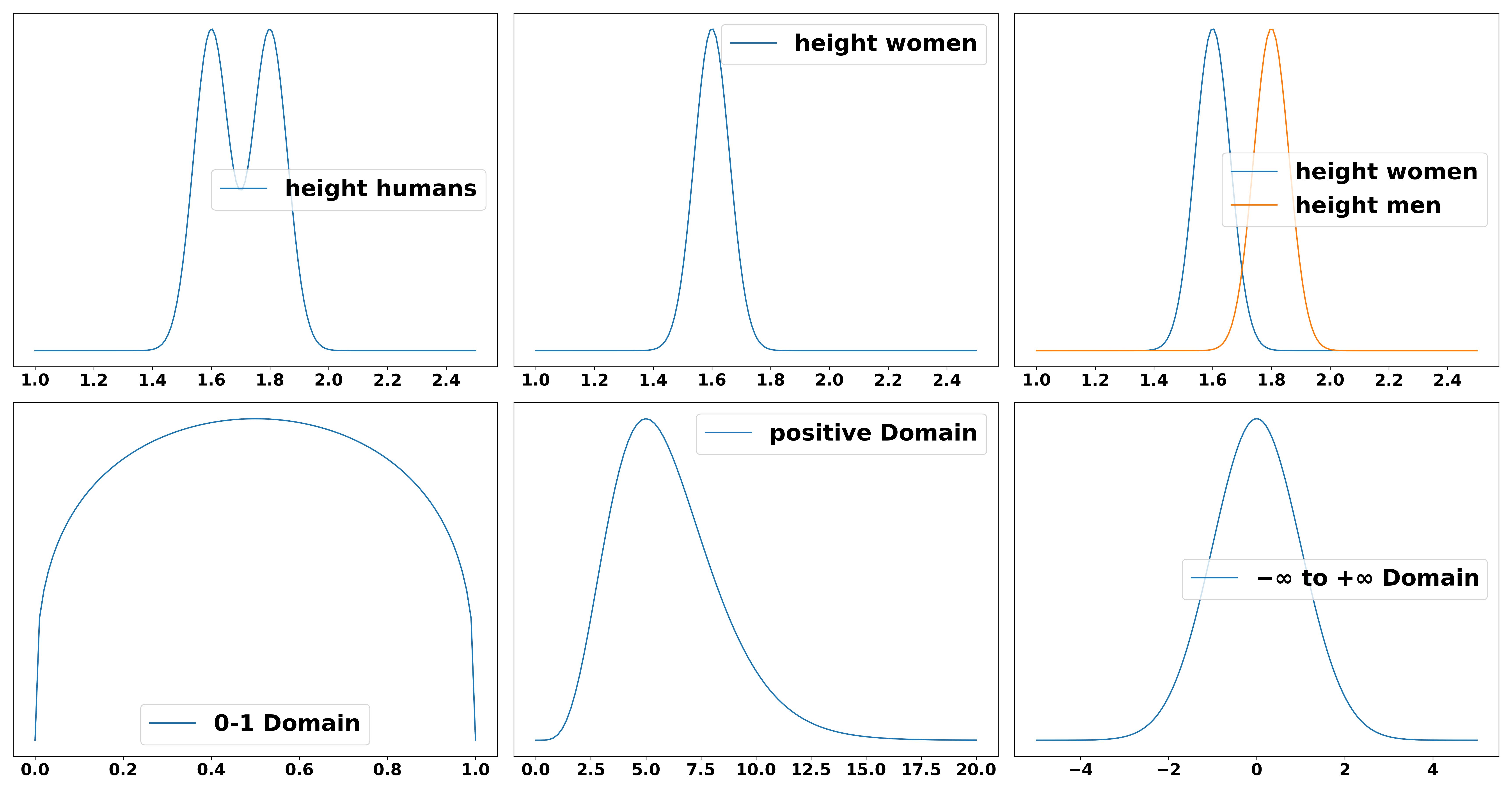

A probability distribution denotes the probability \(p(h)\) of a variable \(h\) taking a certain value, for example the probability of a human to have a certain height. It is more likely that a person is 1.8 m tall than that they are 1.0 m or 3.0 m tall. It is also possible to condition that variable on another variable, i.e. we could look at the probability distribution of height conditioned on the gender \(g\) of a person \(p(h \vert g)\). Even though this is not true in reality, assume for simplicity that there are only two genders. The distribution of the height of all people can now be explained by the two conditional distributions \(p(h \vert g=female)\) and \(p(h \vert g=male)\). Distributions can be defined on different domains. A distribution over probabilities, for example, can only range from 0 to 1 since probabilities below 0 or above 1 are just not defined. The distribution over the height of humans could technically be infinitely large but never below 0. The distribution over the amount of money on your bank account could in theory be everywhere between minus and plus infinity, i.e. you can have anything between infinite debt and infinite amounts of money (disregarding some real world constraints). To understand what probability distributions, conditionals and domains mean, consider the following figure.

Distributions can be used to illustrate a fact about the world as shown in the example of height. However, they can also be used to update our beliefs given new data. Let’s say, for example, your current belief is that human height is distributed around the two peaks of 1.60 and 1.70 meters as shown in the above figure. Now you receive new information: The data that we have based that belief on are ten years old and the decrease in human malnourishment has led to an average growth of humans of 5 cm. Therefore you update your belief to a new distribution that is centered around the peaks at 1.65 m and 1.75 m respectively. There could also be other updates for this believe, e.g. it might be found that the women whose height was measured during the initial measurements were selected from a particular group in society and therefore bias your result. For example, only German women were measured because the study was conducted in Germany. Since German women on average are slightly taller than the global average your updated distribution would include this fact and change the peak for women from 1.60 m to 1.55 m. This notion of updating our beliefs can be expressed via the fundamental rule of probabilistic inference: Bayes rule.

\[\underbrace{p(X\vert Y)}_{\text{posterior}} \propto \underbrace{p(Y\vert X)}_{\text{likelihood}} \underbrace{p(X)}_{\text{prior}}\]We have a certain prior belief about a state in the world, we get new data (here referred to as likelihood) and update this belief to yield a posterior. The posterior asks: “what is our belief about variable X after having seen data Y”, i.e. what is our updated belief?

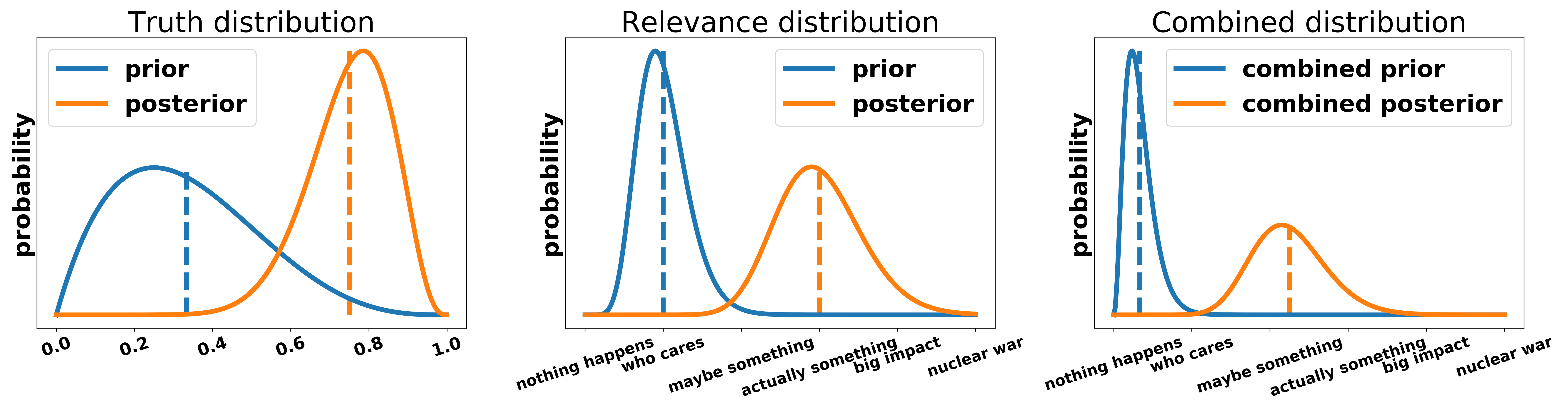

I think persuasion can easily be integrated into this model. As already motivated in the introduction there are two necessary conditions for an argument to be persuasive: it must be true and relevant. The truth distribution lies between 0 and 1 and describes how likely an argument happens in reality. The relevance distribution describes how much of a moral value is lost or gained if that argument leads to the claimed outcome. This moral value can include anything that humans generally like or dislike, e.g. suffering/happiness, freedom, equality, democracy, etc. I want to make very explicit that this framework can be used with any kind of moral metric and NOT restricted to utilitarian arguments.

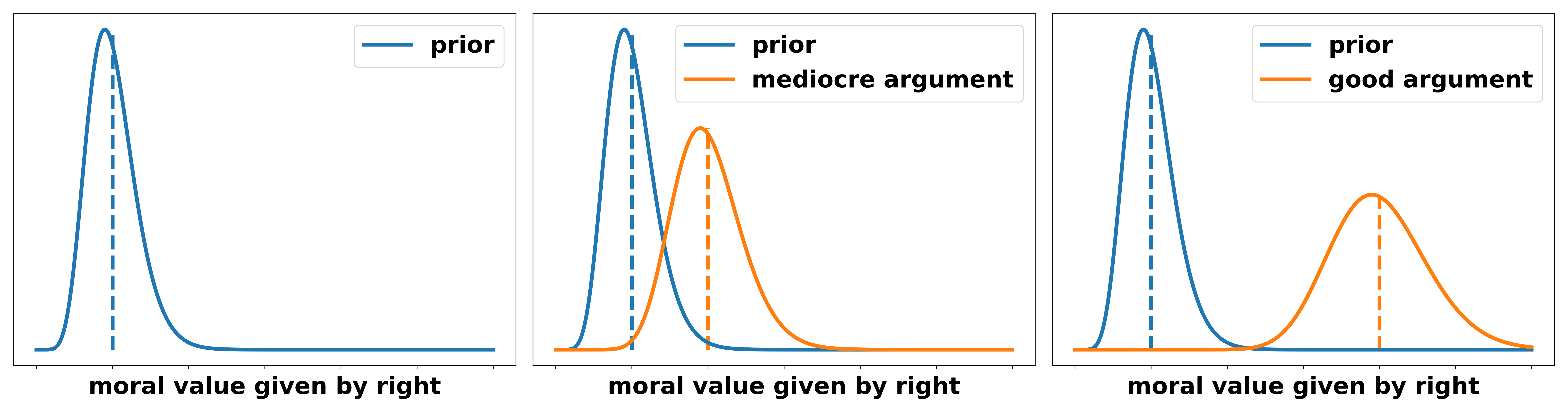

An adjudicator has the prior believe of the average intelligent voter/global citizen (AIV). This prior exists for truth and relevance and is updated through the speakers contributions. The updates should be proportional to the strength of the presented arguments, i.e. a very strong argument must lead to larger updates than a weak one. The final weighing of an argument can either be done by considering the entire distribution or by its expected value (the vertical line in the figures). To summarize: I posit that for every argument there is a distribution over the truth of the argument \(p_{\text{truth}}\) and a distribution over its relevance \(p_\text{relevance}\). Both of these distributions follow Bayes rule, i.e. the adjudicator has a prior believe about them and updates them according to the arguments made in the debate. The two distributions are combined to yield a distribution over the entire argument.

To make this abstract notion more clear, we apply it to a motion with two different arguments.

Example Motion: UBI

Assume the motion is “THW introduce a universal basic income (UBI)”. The model introduced by the goverment is simple: ‘Cut all social benefits, tax the rich and introduce a 1000 dollar per month payment for every person that has citizenship. People without citizenship still get all benefits they have previously received. Parents get the money for their children until their 18th birthday.’ In the following I want to discuss two arguments, a utilitarian calculus and a principle right, that could both be made by a government team. Additionally, I want to illustrate how the prior to posterior distribution shift could be viewed for different possible mechanisms and impacts of the respective argument.

Argument I: a utilitarian calculus

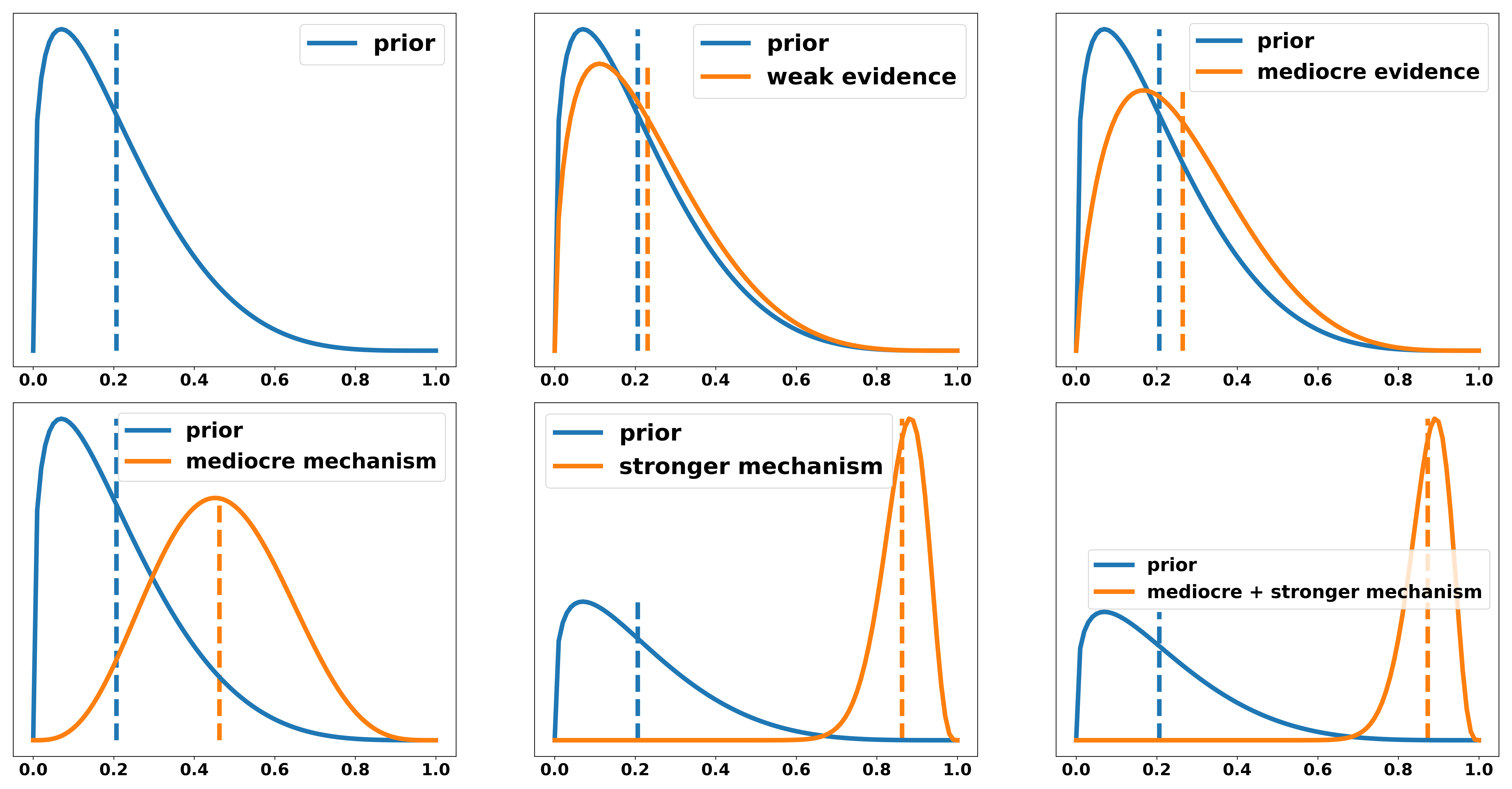

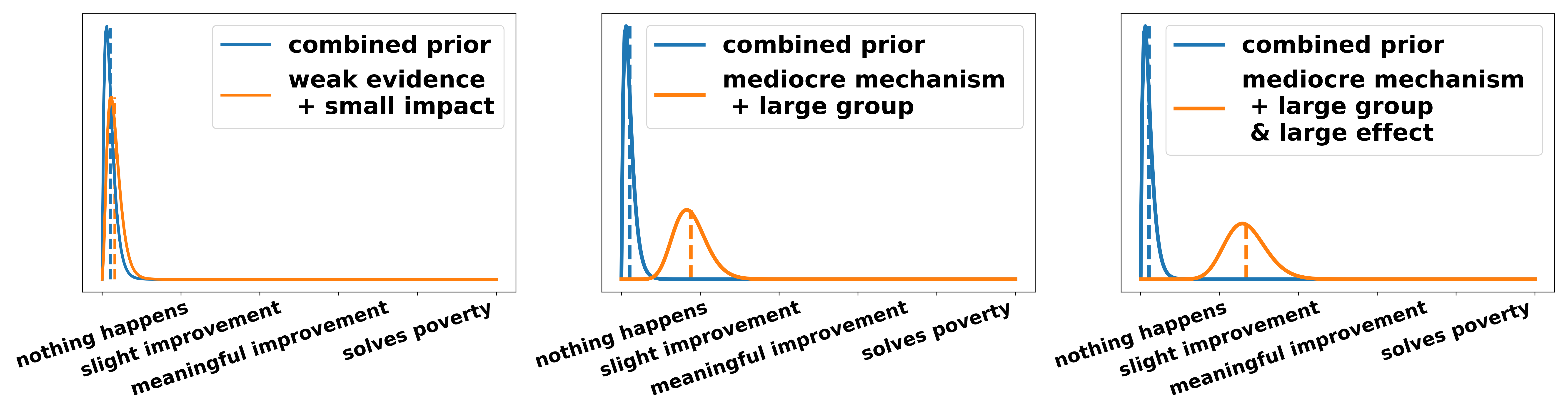

The government claims: “Introducing a UBI improves peoples lives.” To evaluate the overall persuasiveness of this argument consider different scenarios for the distribution of the truth value of this statement. In increasing strength we have

- An emotional story of a friend that could buy themselves a new car. We will call this weak evidence.

- Someone pointing out that this has been tested in small scales in some countries with some positive results. However, they do not explain why this experimental setting is transferable to larger society. We will call this mediocre evidence.

- A weak mechanism: money is nice for people since it allows them to buy goods they like and need.

- A strong mechanism: For a large group of people it removes the fear and uncertainty of low and unsteady income, i.e. not knowing whether they will be able to pay the rent or go to college.

- The weak and strong mechanism are both explained to support the thesis.

Note, that I do not say mechanism 4 is necessarily stronger than mechanism 3. Let’s for the purpose of this example assume that it had been explained more persuasively (e.g. better analysis, more depth, etc.).

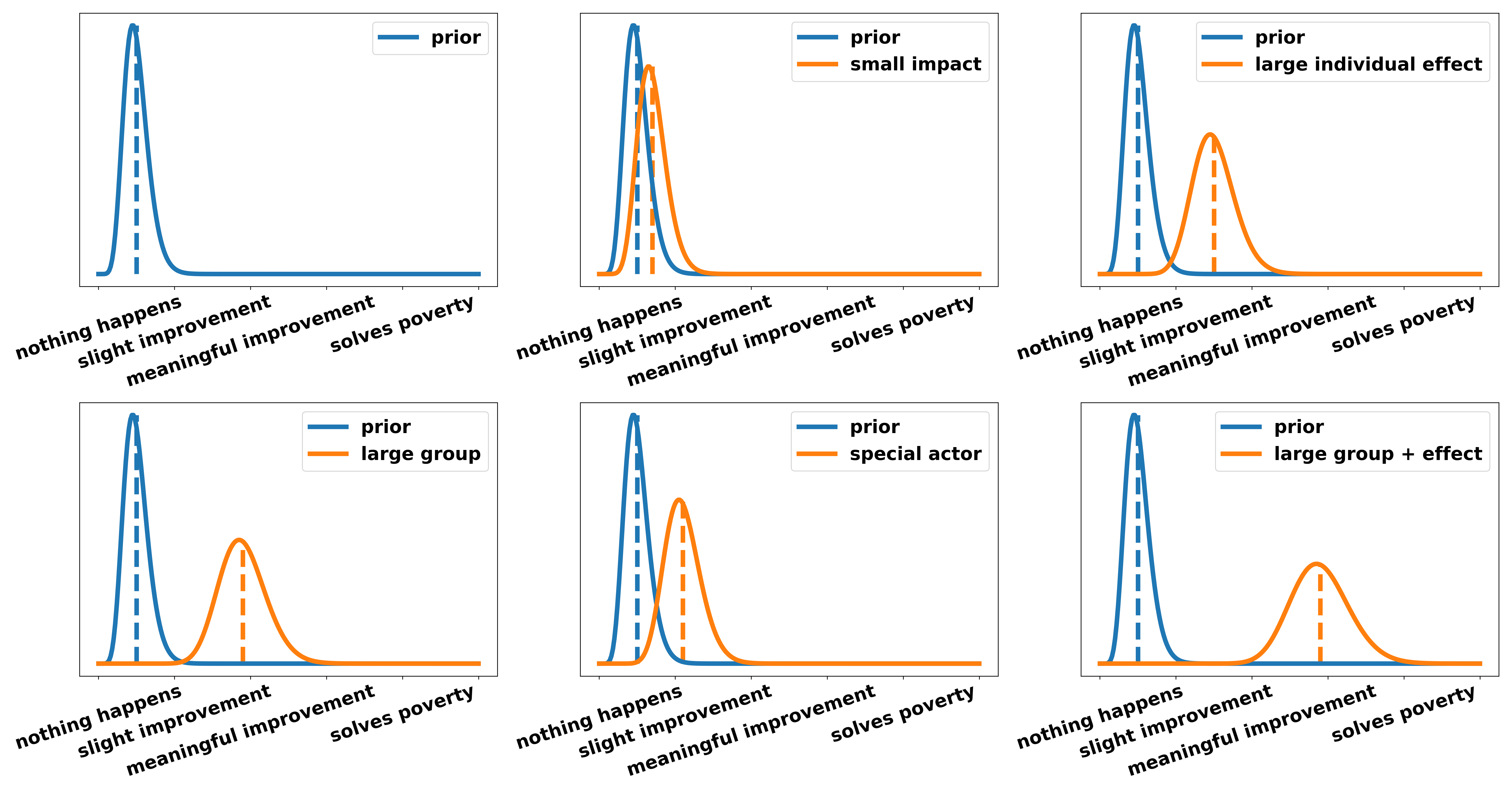

Now, let’s assume any number of reasons why the UBI improves people’s lives have been presented and we are now left with the question: “Why should we care about this?”. This is the second part of the argument, namely: relevance. In the following, we look at the relevance created by different lines of argumentation under the assumption the mechanism leading to this effect has been shown to be 100 percent true. Again in increasing order, we have:

- A small amount of people is helped. For example, with UBI middle-class families can afford an additional holiday per year. This is nice for them and increases their happiness marginally (small impact).

- The individual effect of a UBI is very large. The fear and uncertainty accompanying a low and unsteady income is huge. Not knowing whether you are able to pay the rent for the next month or the tuition for your children is a heavy emotional burden. There is good psychological evidence showing that this “nagging in the back of your head” has an equivalent effect on your psyche as not having slept the last night. Alleviating people of that burden has large individual effects.

- A large amount of people is helped. A UBI with accompanying rich tax is essentially a way of redistribution. Therefore around 90 percent of society gain something while only 10 percent lose out. Therefore a large group is helped (large group).

- An especially important actor is harmed/helped. The individual effects described in 2) hit the most vulnerable groups especially hard. Single parents, low-income families, people in disenfranchised communities (i.e. people of color or immigrants) are disproportionally affected by this uncertainty because they earn less on average and have smaller financial safety nets. Since they never chose to be born within these explicit circumstances but ended up in them through the lottery of birth we should care about these actors more.

- Any combination of the above. For example, a large group and a strong individual effect (large group and large effect).

Now we have to combine the two posterior distributions over truth and relevance. If we only considered one of the two it would be rational to either only argue claims that are uncontroversial, such as “this motion helps at least one individual a little bit”, or claims that have gigantic effects, such as “This motion will lead to a nuclear world war”. To illustrate how different distributions over truth and relevance interact I chose three distributions over the truth part and three over the relevance part and show some combinations of them.

Argument II: a principle right

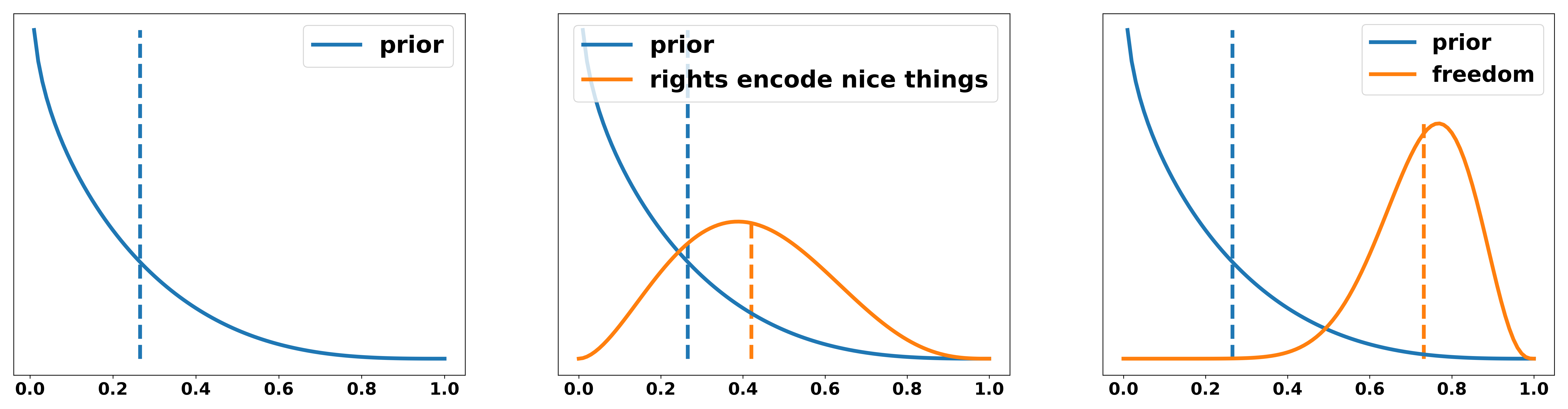

The probabilistic framework is independent of the moral system that an argument is based on. To illustrate this fact, I want to give the following statement as a non-utilitarian example: “a UBI is a principle right that every person deserves to have”. Different reasons for why this argument is true are shown in increasing persuasiveness:

- Rights encode things that are nice. Having more money is nice. Therefore UBI should be a principle right.

- UBI is directly linked to your right to make free decisions. Without the certainty of receiving money unconditionally, you always have to either work (often in bad conditions for a minimum wage) or you have to fulfill all conditions to get unemployment benefits. Even though they are supposed to be a safety net they often require lots of bureaucracy or are linked to your will to seek work. This means you are not able to make the decision not to work to educate yourself or any other reason. Therefore, not having an unconditional source of income is equivalent to taking away your ability to make completely free decisions.

We can again illustrate the degree to which these arguments change our belief in the following:

The probability distribution over relevance can equivalently be applied to a rights-based argument. We essentially ask the question: “how much more of a moral value would be granted to individuals if UBI existed” or, given that in rights argumentations we often frame rights as something that you have just by existing, we could ask: “how much of a moral value is infringed upon if individuals do not have that right by law”. Again, two examples for illustration:

- By not having a UBI an individuals access to happiness is reduced to some extend. Not having free money implies not being able to buy certain goods that would make you more happy, i.e. video games, a new bike, more expensive clothing or food, etc.

- By not having a UBI individuals access to free choices is reduced to a large extend. The choices that people are unable to make due to money constraints have long-term consequences that restrict their freedom even further. If, for example, someone has less wealthy parents and is therefore unable to pay for their education (even if education is formally free in many western countries, you still need to pay for rent and food) this person can’t take the opportunity to study. This is an obvious short-term restriction on their freedom. If they didn’t study they might not be able to access a lot of jobs they could have otherwise gotten and, on average, also earn less money. This further restricts their freedom and to some extend the freedom of their children to make similar decisions. A UBI solves this and therefore gives more long-term freedom to individuals.

Now we combine the distributions over truth and relevance to get a full distribution over the argument.

In the following I want to discuss some of the choices I made and questions that the probabilistic framework naturally poses.

What about the priors?

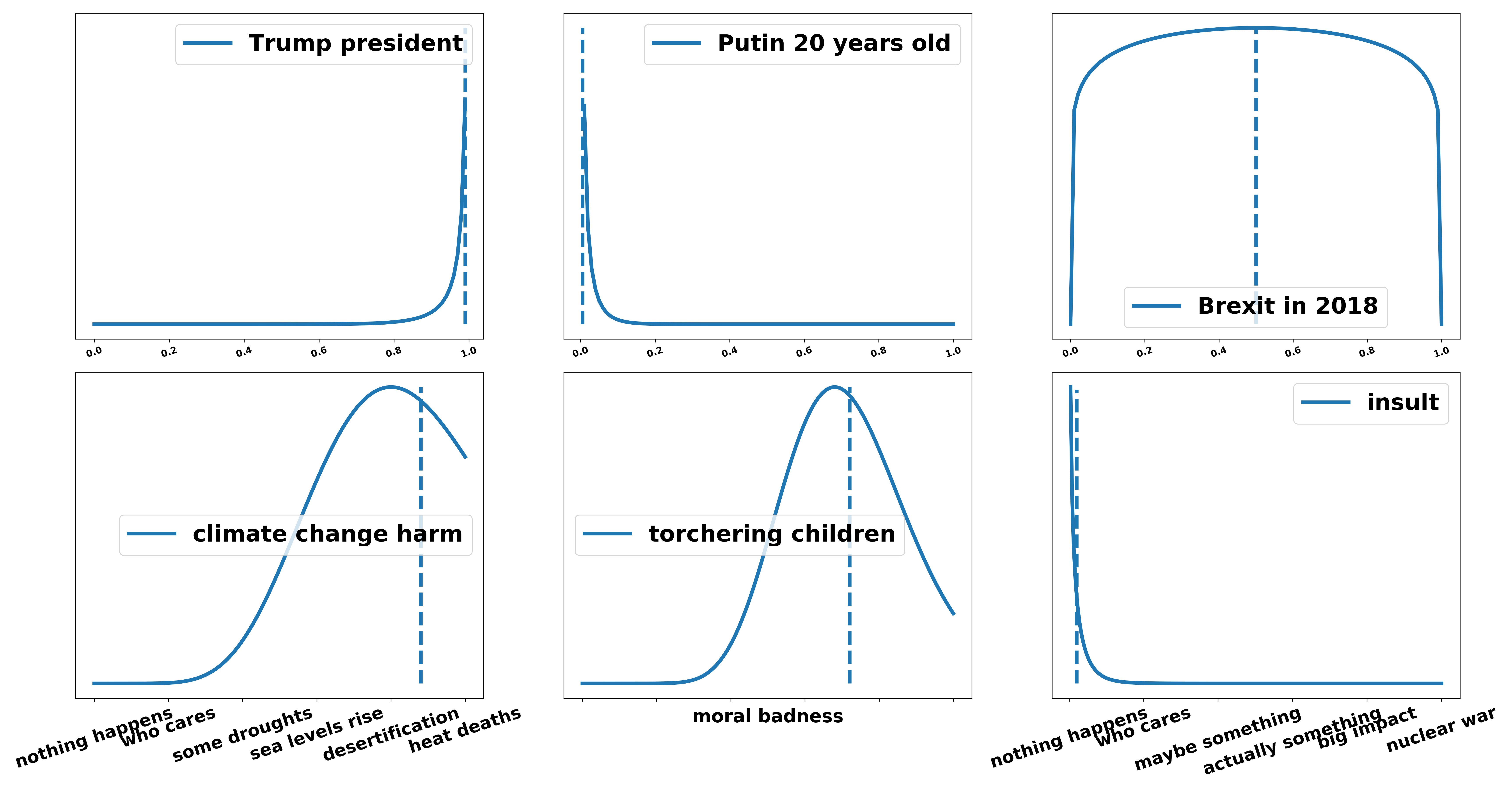

A criticism of Bayesian inference is: “Your posterior depends on the prior and if you choose the prior in specific ways you can produce whatever results you want. Therefore Bayesian Inference does not work.” While this is true in some (but not most) real life applications that it is hard to choose a prior that makes sense we could also choose a prior that just says “I actually really don’t know. All options are equally likely.” However, in debating, there is a simple way to choose the priors that we already agree on. In every judging manual you will find that the “Average intelligent globally informed Citizen” or “Average Informed Voter” (AIV) is the basis of adjudication. Stefan Torges addressed this problem in his 2017 article (article in German) on the debating website AchteMinute and I extend and illustrate his line of argumentation. It is clear that the AIV has prior knowledge. For example if I asked you what your belief about the statement “Donald Trump is currently (January 2020) the president of the United States”, then you would be very sure that this is a true and not a false statement. Maybe there would be some lingering uncertainty because he could have been impeached while you were asleep but you would, in general, be very certain. For the statement “Putin is 20 years old in 2020” your distribution would very much lean to the false end. If you were to assess the statement “Brexit will happen” in 2018 the past AIV would have very high uncertainty over the truth of the statement, probably including all possibilities from false to true. This also holds for the relevance of a given statement. For example, the prior distribution over “the harms of human made climate change” is definitely rather large (possibly with a wider range of options) or the prior distribution over “the wrongness of torturing children for fun” is definitely at the high end of badness. The negative effects of one minor insult are rather small and so is the AIVs respective prior.

All the knowledge that the AIV has should be seen as prior knowledge. There is obviously not a list of things that the AIV knows and therefore this question can not be definitively answered but at least we have a clear way of solving disagreements during adjudication.

However, I must point out that debating is a game that implies rules for how the priors are distributed. First, prior knowledge must align with the reality of the AIV, i.e. they know basic facts about the world but are not specialists in any particular field. They know the presidents of most major countries of the world, some basic economics and politics, etc. They do not know the finance minister of the Kongo, the exact melting point of all metals or the exact wording of the law of every country in the world. Even if a particular adjudicator knows these facts, for the purpose of the debate, they must assume not to know any of them. Second, priors should be sceptical rather than naive, i.e. the burden is on the teams to show that something is true and the adjudicator should not place too much confidence on statements that are not well explained. Third, prior knowledge distributions must be easily shiftable, i.e. the adjudicator is easily persuaded by arguments when good reasons are presented. This level of persuadability is probably a lot higher than for the average person but is part of the game we play. This does not solve the issue of priors entirely but merely shifts it. It is for example unclear whether the AIV intuitively agrees with the statement: “Quantitative Easing hurts the economy in the long-term” or if they are even supposed to know what Quantitative Easing is in the first place. This is a problem that we cannot solve independent of the probabilistic framework but I think forcing the adjudicators to explicitely think about the priors of the AIV decreases the difference in perception of arguments at least a bit and gives a framework to solve disagreements. Now we can more easily ask: What are the AIVs priors and how does this change our perception of the argument?

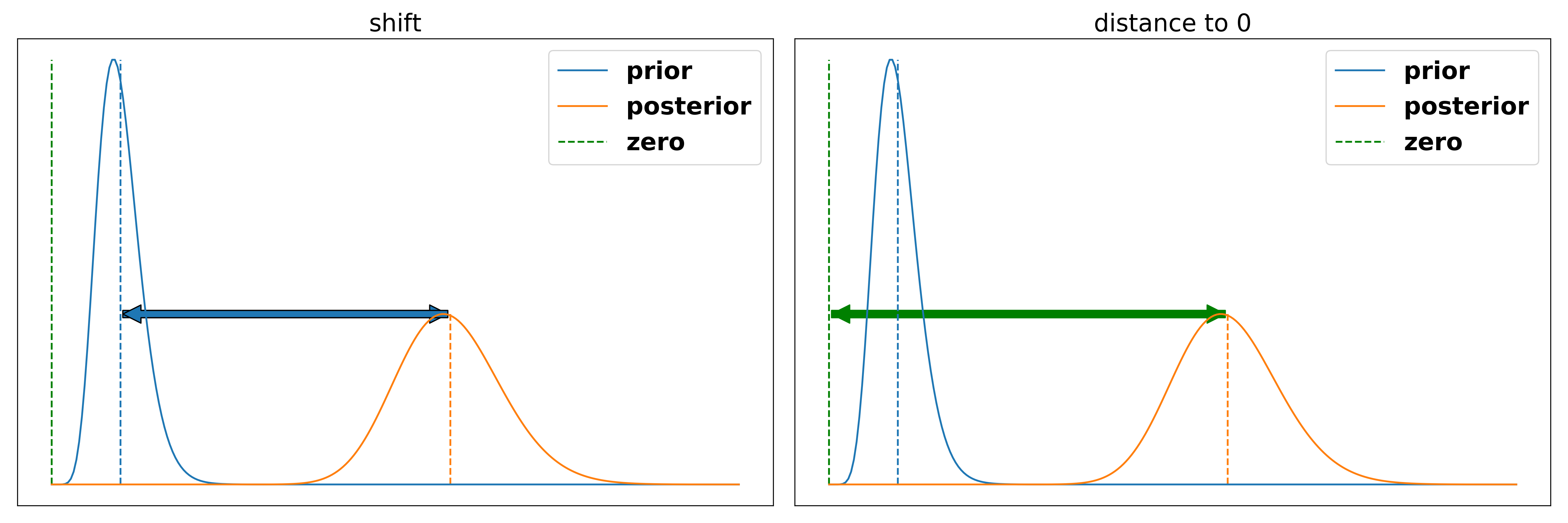

Prior shift vs. Distance to zero

There are two different philosophies that could follow from the proposed framework. Either you could say the degree to which the person changed my belief from the prior to the posterior is the correct way to judge their contribution or the absolute value of the posterior, i.e. the difference between zero and the posterior.

Honestly, I am a bit uncertain myself about the correct way to assess the argument. In a real-life situation we care about the distance to zero. If we have a large prior that something is a good idea and it gets shifted a bit to the negative we would still tend towards acting upon that idea. In debating, however, we want to reward the teams for being able to change opinions and therefore might want to reward the change more than the objective effect. I am currently undecided between both metrics. The shift in belief carries the problem that “surprising” arguments, i.e. ones that are not expected by the AIV, are more convincing even if the posterior is lower. The distance to zero carries the problem that it might make it nearly impossible for a team to win an unbalanced motion from the harder side. However, I think there are two aspects which make the difference between these views rather small.

- We assume that chief adjudicators give their best to produce balanced motions. This means that there is no large difference between the shift and absolute distance metrics, at least between the sides of a debate.

- As argued above our priors are skeptical anyways, i.e. the teams need to give reasons to shift them. This implies that most of our priors are close to zero and the two metrics yield nearly similar results.

Why does this framework matter in practice?

- Outside of debates: Having a more or less formal framework of persuasion and adjudication is helpful because it brings people on the same page and forces them to think about inconsistencies in debating when an aspect is not easy to integrate. I, for example, had to realise that my understanding of “rebuttal is constructive” was rather vague and inconsistent. Explaining it through the probabilistic framework forced me to come up with a consistent solution.

- In a debate, especially when adjudicating: Obviously, I am not asking you to explicitly calculate the distributions over the teams arguments within a debate. This framework is more of a mental assistance for the complicated process of adjudication. Within 15 minutes we have to coordinate different views on a one hour debate and come to a decision. Fast and unified communication is key. When two adjudicators disagree about an argument, we can, for example, ask whether this disagreement is reasonably explained by the variance of the AIVs view on this argument. We can decide whether something was an extension by trying to identify to which degree the opening’s argument convinced us and then compare it to the degree that the closing’s argument furthered that belief.

Limitations of the model

This framework/illustration is obviously not perfect and I want to point out some of its limitations.

-

Human communication is weird, we don’t talk in logic: Most of the time, teams do not make an argument in strictly logical terms. Instead of showing why a claim is true and relevant we often just concatenate sentences and convey some sort of argument without actually following the logic. However, as in the status quo, it is the judges’ task to distill the logic from the speeches and compare it with each other. If the logic is too hard to extract because the speech was hard to follow (in a logic not language sense) then it is impossible for the judges with or without the probabilistic framework to make an informed decision.

-

Overlap between truth and relevance: As you can already see in the first example for UBI, sometimes there is an overlap between the truth and relevance part of an argument. Explaining why it is true that someone is negatively influenced already to some extend shows that this influence is negative. Even though this might make the model “less distinctive” or “less clean” I do not think it is a big problem. In the end truth and relevance are combined anyways and it therefore does not matter whether the influence on the combined belief comes from the truth or relevance part as long as it is not counted twice.

-

Relevance sometimes has lower priority: In some debates the goal of the argument is undisputed, i.e. all teams agree that a certain thing is either desirable or undesirable. Therefore the relevance part of an argument becomes less important. This might include claims such as “climate change is bad”, “more jobs are good”, “democracy is desirable” or “undeserved suffering is bad”. The more important question in these debates becomes whether the claim the teams are making is actually leading to the desired outcome, i.e. to which degree it is true. Therefore, the truth and relevance framework is sometimes reduced to a “truth only” framework.

-

Hierarchical models: Theoretically, we could add infinite layers of priors to all of our beliefs. The prior of the AIV could have a meta prior about what the AIV is able to understand and think. This prior could have another prior, etc. The same can be done for every argument since you can model all assumptions about reality in a hierarchy of priors. However, the model would become so complicated and confusing that I have decided to exclude all of these parts and focus on the basic understanding first since the purpose of this post is illustration and not building a computational model.

Nerd section: some statistical explanations

- Bayes rule not Bayes theorem: Some of you might have seen Bayes formula already and therefore know it with the evidence term \(\int p(y \vert x)p(x)\). This is the difference between Bayes rule and Bayes theorem, where the theorem uses the evidence term (i.e. the integral) to normalize the distribution to 1 such that it truly is a probability distribution. However, since we do not model Debating in a computational sense but rather to clarify and understand some of its peculiarities I have chosen Bayes rule to keep it simpler.

-

The distributions I have chosen for the models of truth and relevance are the Beta and Gamma distribution. All other distributions that are on the correct domains would also be fine. For the illustration of probabilities in the beginning I chose the Normal distribution since is the most known distribution and also fits best to model height.

-

To combine two random values by multiplying them you usually have to sample from both and multiply the samples to get a histogram over the new variable if they are not conjugate to each other. This would also have been possible but introduces another level of complexity. Therefore I have decided to just multiply the Gamma (relevance) distribution with the expected value of the Beta (truth). Even though this means that the variance of the truth distribution is not modeled perfectly I chose to trade this off for understandability.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Julian, Samuel, Bea, Maria, Marion, and Anton for the fruitful discussions, elaborate feedback and grammar-nazi skills (probably still contains some typos though).

One last note:

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.