What is this post about?

Most debaters know the experience of losing a debate and feeling completely misrepresented. The judges seem like they have not even understood half of your case. After personal feedback, you conclude that the judge is clearly incompetent and should have listened more carefully. While this might sometimes be true, most of the time you are at least partly guilty as well. To reduce the number of times these unfortunate scenarios arise we have to look at the reasons for this miscommunication and think about solutions to them.

Where does all the confusion come from?

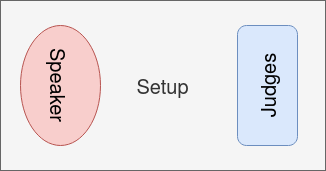

Human communication is already hard outside of debating. Adding pressure and removing instant feedback definitely doesn’t make it easier. I think we can broadly categorize the communication in a debate in three parts: the speaker, the judge, and the setup. The setup describes the general context of the situation, e.g. that speakers talk while the judges only listen and write, the fact that there is no instant feedback, that speeches are 7 minutes, etc.

-

The Speaker: We always think we have said more than we actually did. This is the case because the largest parts of our thinking process are not shared. Our imaginations, our associations with the argument or the words we use, the scenery we picture in our head while explaining something - all of these are things that we see clearly in front of our inner eye but are invisible to everyone else. Even though this is not new information for you, it is still impressive how easy we forget the extent of this effect. Just describe an image as accurately as possible to a friend and have them sketch it from your description. You will be surprised how much of the “obvious things” they missed from your explanation.

-

The Judge: Adjudication is a very hard task. You have to listen to a person talking, distill the relevant information and write it down while still listening to new information. At the same time, you have to already integrate this information into the larger picture of the debate and filter out some of the absurd claims thrown at you. It is nearly impossible that no information is lost along this path.

-

The Setup: There are many ways in which debating is different from a normal conversation (for which most of our communication is optimized). There might be weird background noise - an AC or a heater buzzing in the back, a different team that is unable to whisper, etc. But even in more optimal conditions, the setup plays a large role. On the one hand, there is no instant feedback. If something is unclear in a normal conversation the other person would just ask a question, wherein debating, you have to anticipate the question and answer it preemptively. On the other hand, there is a difference in the distribution and reception of information. While the speaker desperately tries to stuff as much information as possible in a seven-minute speech and therefore talks very fast the judge has to write down a short version of the content. Just the fact that writing is slower than speaking should already inform the way we debate. Lastly, a speech is seven minutes long. Using precise language means more information per time.

How can we address these problems?

-

Re-order the logic: Conversational logic often follows the scheme of “A is true AND B is true THEREFORE C is true”, e.g. you would say “I went to the store today (A) but it was a Sunday and the store was closed (B) therefore I didn’t get you any chocolate (C)”. This conversational structure has the disadvantage that judges are left in the dark until the very end of the argument - there is no clear structure to anticipate. I think it’s easier to flip the logic to “I want to show C; Reasons for C are A and B”, i.e. you want to take the conclusion of the argument and rub it in the face of the adjudicator. While this would ruin most daily conversations because it kills all the suspense it helps you in debates exactly because you don’t want any suspense. If you are interested in how this affects extension speeches, I would recommend Teck Wei Tan’s workshop.

-

Redundancies: Because you speak faster than the judge is able to write it is important to include some forms of redundancy to let them catch up. I think a good way to do that is by first stating the mechanism in a general fashion and then backing it up with a more narrow example to illustrate this mechanism. Let’s say you make the following argument in your speech: “Private News outlets have profit incentives and therefore need to tailor their shows to the worldview of their customer base even if that means bending the truth. Fox News, for example, has to misrepresent the data on gun ownership to reinforce the beliefs of a conservative follower base.” This might end up as “News profit incentive -> tailor worldview to customer (Fox News & Guns)” on the judges’ notes. While the example is not necessary to understand the mechanism it has two important functions besides catching up. First, the judge can double-check their understanding of the mechanism and second, if the judge did not understand the general mechanism they can extrapolate it from the example to fill the gap. The level of redundancies depends on the importance of the statement. If it is a necessary step for your main argument maybe drop a second example if it is the fourth reason for some argument, explain the general rule and go on to more important stuff. Additionally, you can introduce a “Hedge-section” after important arguments in which you explain your argument in a fool-proof manner and preempt common misinterpretations. You could, for example, say “The opposition will try to tell you that only a few individuals are affected by this policy and we should therefore not care about it. However, you should not underestimate the magnitude of the effect on these individuals”.

-

Clarity > proficiency: For a long time when I stood in the front I was in “speech mode”, i.e. every sentence has to be correct, clean and proficient. Some people go even further than I did and pretend to hold a state of the union address to the nation whenever they give a speech. Not always, but often, this level of rhetoric comes at the expense of clarity, e.g. we use a fancy word not because it makes the most sense but rather because we want to signal that we know the fancy word. I recommend completely losing the “statesman” mentality and using basic language. There is no need to perform a poem on “the magnitude of suffering during a famine” when saying “having no food is really bad” is completely sufficient. There is also no need to use grammatically correct sentences. As long as the message is clear nobody cares whether you butcher the grammar. As a basic rule, you should mostly use main sentences. Subordinates greatly complicate your structure and reduce information-delivery efficiency. As I will discuss in the next point there are obvious advantages of being very proficient in a language but what I really want to stress here is that a) there is no shame in using simple language or incomplete grammar and b) don’t waste time searching for a fancy word when you can use a basic one.

-

Use common references: In some situations you can save a lot of time and gain clarity by referencing already existing public knowledge. This includes metaphors, analogies, simple examples, or correct technical terminology. An example of an analogy would be when a team defends legalizing drugs and props it “similar to alcohol and tobacco”. This little sentence just saved them two minutes of modeling and rendered much model criticism from OO completely useless. Describing a situation as an “A blessing in disguise” already provides a certain framing for the judges that is hard to achieve otherwise with similar efficiency. It is also helpful to know some basic technical terminology for most fields of research. Describing something as a “prisoners dilemma” saves you the hassle of repeating “a situation in which the incentives of the individuals are not aligned with the common good” over and over. This should only be done if you expect other teams or the judges to know these technical terms. If they get too specific you are just talking gibberish to them. Also, keep in mind that using a general concept does not replace an actual explanation. If you just say “prisoners dilemma” you have not shown why the motion actually leads to one and cannot be used as a substitute.

Some concerns

Doesn’t this hack debating?

You might feel like this is some kind of reverse engineering of the adjudicator and therefore a wrong thing to do. However, the judges and other teams profit from a style that is more clear and understandable. Everyone wins.

Criticism by Lennart Lokstein

Lennart summarized his concerns as follows:

- Listeners want to root with someone they like or/and represents ideals they identify with. Thus, the speaker in their speech must be fun and entertaining (as it’s their only way to show their character to the audience in that setting).

- For the same reason, fancy words to some extent can be useful, because it’s a way to show being educated.

- Judges are, unfortunately, often only looking to capture the content of a speech. This allows them to give calls based on “hard” material (like the exactly phrased sentences) which are easy to defend against unhappy teams. For appealing to those judges (or rather for winning under their adjudication), Marius’ suggestions are indeed optimized.

- However, those judges are far off the mindset of any usual listener - since they are listening to content instead of the speaker, which normal audiences would do. From some BPS perspective that’s all well (or even ideal). From a holistic perspective on persuasive speaking (in general), however, it will lead to a working-but-not-ideal habit of speaking.

I think this is very fair and valuable criticism but would still like to clarify and give a high-level answer: There are different goals people want to achieve with debating. Some want to have a very detailed discussion and be judged based on content and content alone. They might debate because of intellectual curiosity or because it trains valuable analytical skills and clear thinking for future jobs or academic careers. Others might rather want to learn how to speak to larger crowds and convince normal people. Their motivation might be a general admiration of rhetorics or a preparation for future jobs in politics or communication-focused industries. While I think that it is nearly strictly positive for the first group of people to optimize their speeches for efficiency, I agree that this is not true for the second group. If someone wants to convince the general public it is reasonable to follow my suggestions until they acquired a basic level of clarity and understandability but they should then focus on other skills such as their rhetorics. I agree that there are bad practices in debating such as dropping mechanisms without explaining them or that judges sometimes stop listening because they think they understand the argument from the headline. While these might have a vague association with the general idea of optimizing speeches I don’t endorse these bad practices. I thank Lennart for pointing this out and clarified it in the main text. I think that both, Lennart and I, would want a team to win exactly because of the content that was given during the debate and not based on the extrapolations made by the judges.

I would like to thank Dominik Hermle for feedback and suggestions, and Lennart Lokstein for clarifications and constructive discourse.

One last note

If you want to get informed about new posts you can subscribe to my mailing list or follow me on Twitter.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.