What is this post about?

In preparation to move to a new flat, I recently sorted out my clothes. I originally intended to give still usable ones to charity but my girlfriend suggested that this was net negative. She argued that the clothes would destroy local economies in Africa, where they are predominantly sent to, and that the additional emissions through transport would harm the environment. I thought that second-hand clothes would be distributed by NGOs and helped African people in need so that they could spend their income elsewhere. We couldn’t find an agreement since neither of us actually had an overview of the empirical evidence or the relevant data to answer the economic question of “does it destroy the local economy or help people in need?”. To answer this question I did some research. While I hoped to find a rather quick and easy answer that would settle this dispute I was utterly disappointed. Instead of being just an economic question it also involves a lot of historic, cultural, and environmental considerations that I had to dig through.

In this post, I want to show what I learned and which conclusions I, personally, drew. I want to emphasize that I’m not an expert in the field and even though I have read a lot of articles, papers, and reports, and dug into some data, I still don’t feel like I have a perfect understanding of the issue of second-hand clothing. You should therefore take my opinions with a degree of uncertainty and expect some of them to be insufficiently nuanced.

While the debate about second-hand clothes (SHC) is applicable to most countries, especially less developed countries (LDCs), the scientific and societal debate has mostly concerned itself with Subsaharan Africa. Therefore, the main focus of this post will be Subsaharan Africa but some of the discussed problems equally apply to other LDCs. I will refer to Subsaharan Africa as Africa for simplicity in the rest of the post.

The work for this post was significantly more than I originally anticipated and there are lots of interesting pieces that I have not included. If you want to understand the topic further I have included some interesting papers, reports, and data analysis in a github repo.

History and Data

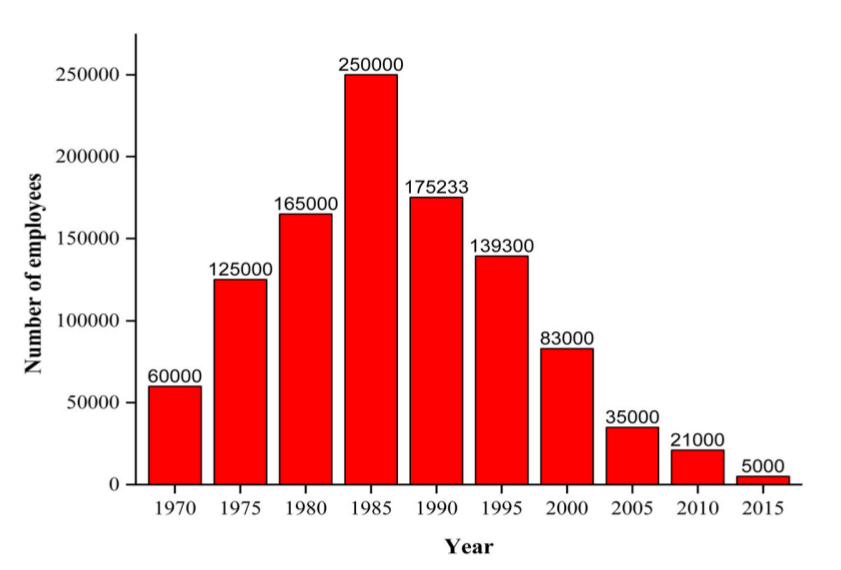

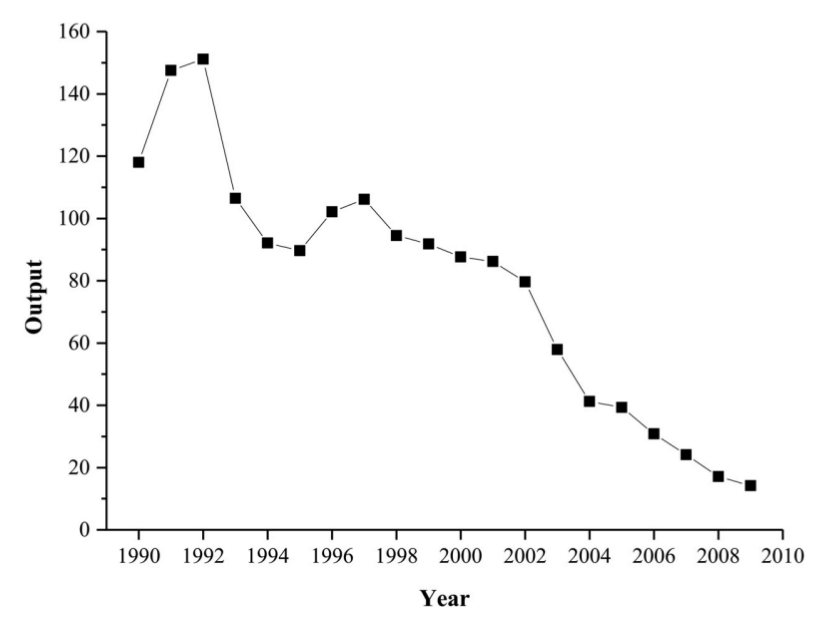

In the 1980s many African countries had a pretty flourishing textile industry. However, over the following 40 years, the industry has largely disappeared. This trend can be seen, for example, in the number of jobs in textile production and the index of output over time for Nigeria

Similar trends - even if not always that drastically - can be found for many other African countries. Ghana, for example, reported a 50% reduction in textile output and an 80% reduction in textile employment in a similar time span. In Zambia, employment dropped from 25,000 (1980s) to below 10,000 (2002). For a more detailed analysis, I can recommend this report by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

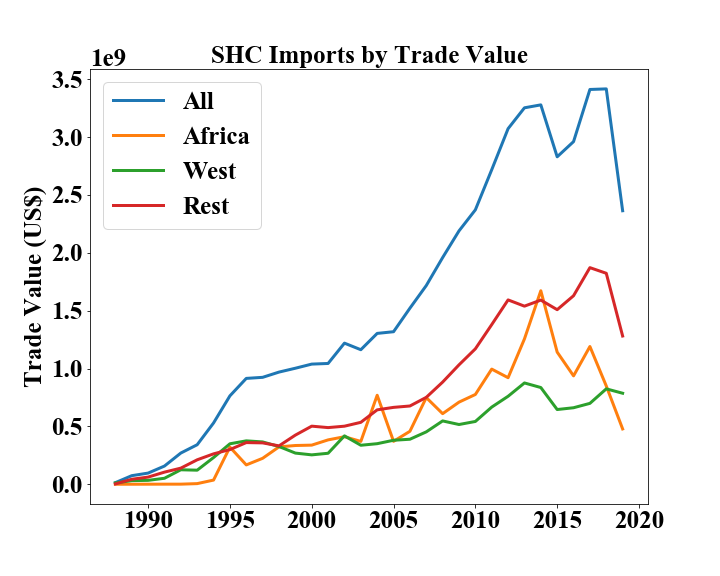

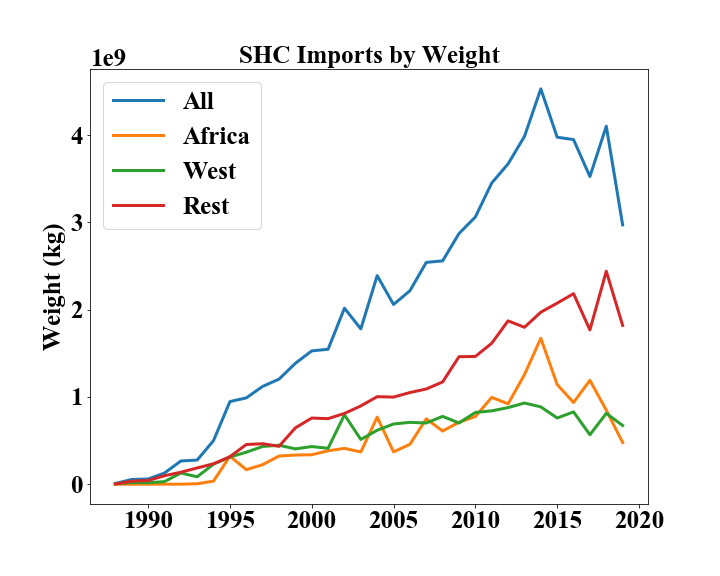

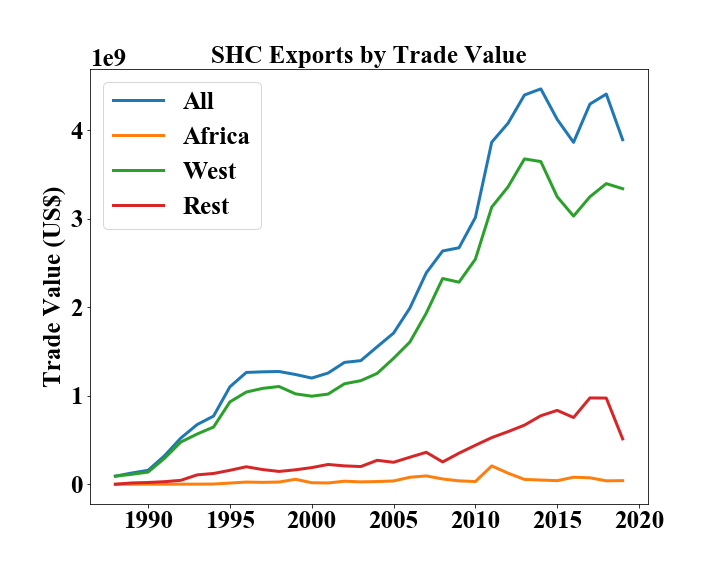

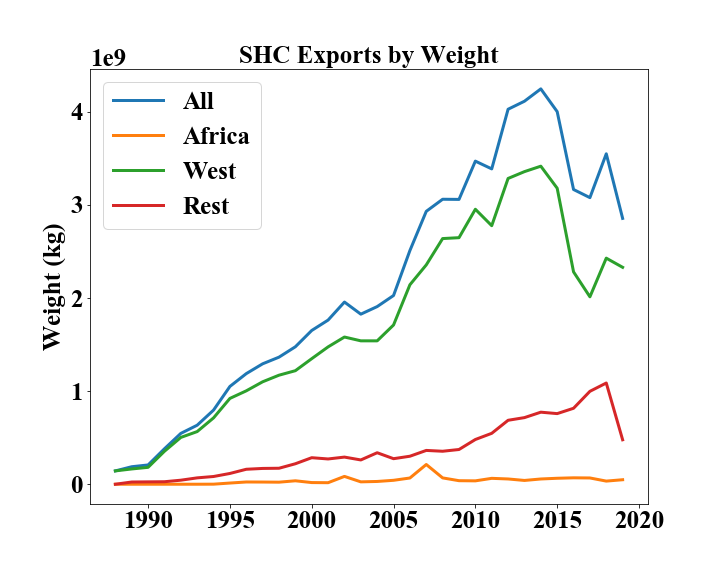

It is assumed that the two strongest reasons for this were a liberalization of the industry and an increase in competition through SHC. To which extend each of these trends is causal or just correlations will be evaluated in-depth in the ‘Economy’ section of this blog post. However, it is undeniable that the SHC trade around the world has increased while the local production of textiles has decreased in Africa. If we look at the COMTRADE data on used clothing we find that African countries import a lot of SHC measured in trade value (left) or weight (right) and that Western countries don’t import as much.

Looking at the other side of the trade - the West exports a lot of SHC while Africa exports nearly nothing.

As a result of the (perceived or real) thread of SHC to local industries, two things changed within the global SHC trade and distribution around 2015 (these also partly explain the drop in trade in the above figures). Firstly, many African countries - especially eastern Africa, e.g. Rwanda, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan, and Burundi - proposed a ban or strong tariffs on the import of SHC to protect their own infant industries. However, the SHC export industry in the USA has a strong lobby with around 40k jobs attached to it that influenced the US government to prevent this ban. As a consequence, the USA threatened the eastern African countries with ‘reconsidering’ their membership in the African Growth and Opportunity Act such that all Countries but Rwanda stepped back from the ban. A good overview of the proposed ban and Rwandas reasons and reactions is given by this NYT article. Secondly, Western governments and NGOs reacted because they realized that their export of SHC might negatively affect local industries or cause other harm. The EU, for example, has put regulations in place that are supposed to stop the flooding of African markets with SHC, and individual NGOs such as Oxfam have adopted policies to only provide aid to regions that are not harmed by it. A longer discussion of what kind of regulations exist and which organizations do a good job can be found in the ‘Reactions and Alternatives’ section.

The strongest reasons for why the SHC trade declined from 2015 onwards are economical ones though, as described in a BBC article. Through the rise of Fast Fashion consumers are getting used to wearing an item of clothing only a couple of times before throwing it away. As a consequence, the quality of clothes has dropped measurably and the costs of sorting, washing, refurbishing, and restyling SHC have outgrown the value of low-quality resales. Therefore, many for-profit SHC organizations in the West have closed and shrunk the overall volume of imports and exports. The old clothes from fast fashion are often not recycled or disposed in the West because of costly regulations. Instead they are shipped to LDCs and burned or dumped into landfills. I won’t go into the details of clothing waste but this video can give you a first glimpse.

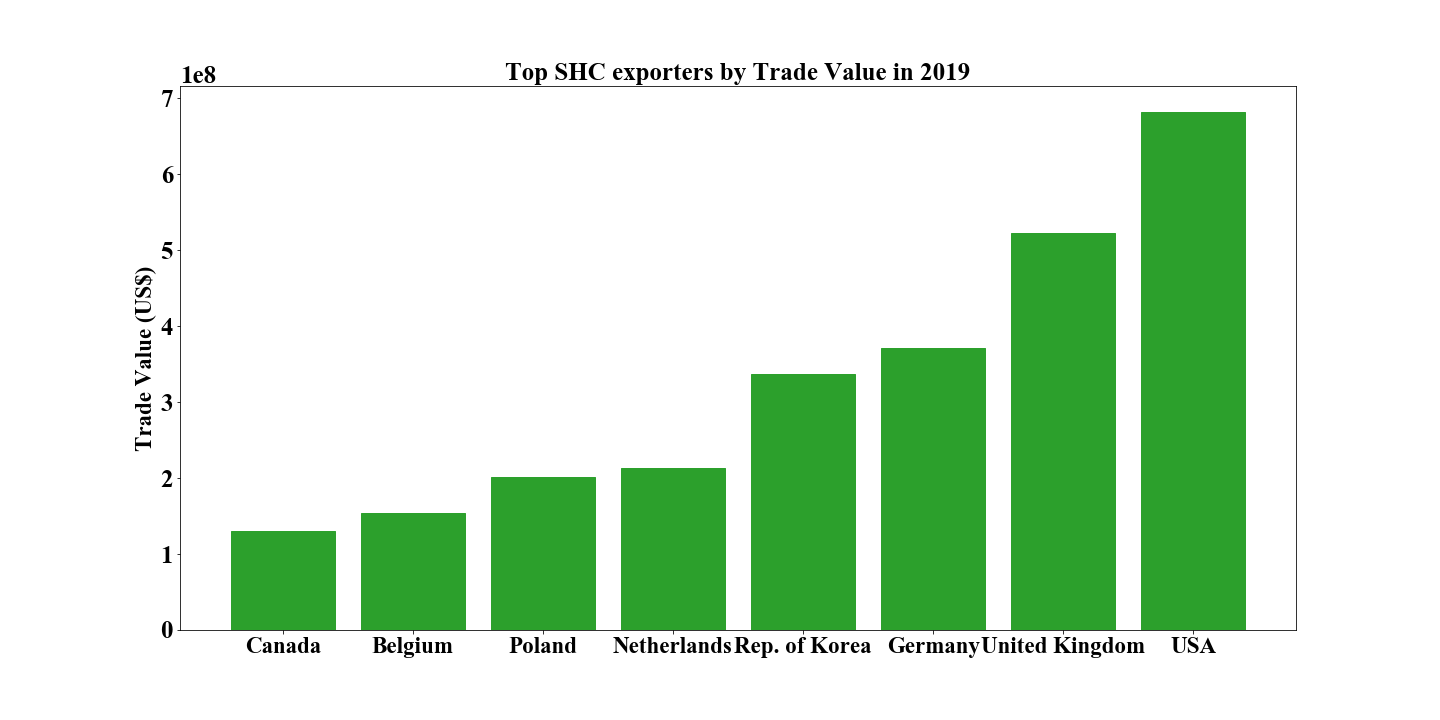

To further strengthen our understanding of the situation of SHC in the status quo we have a look at the top exporting countries in 2019.

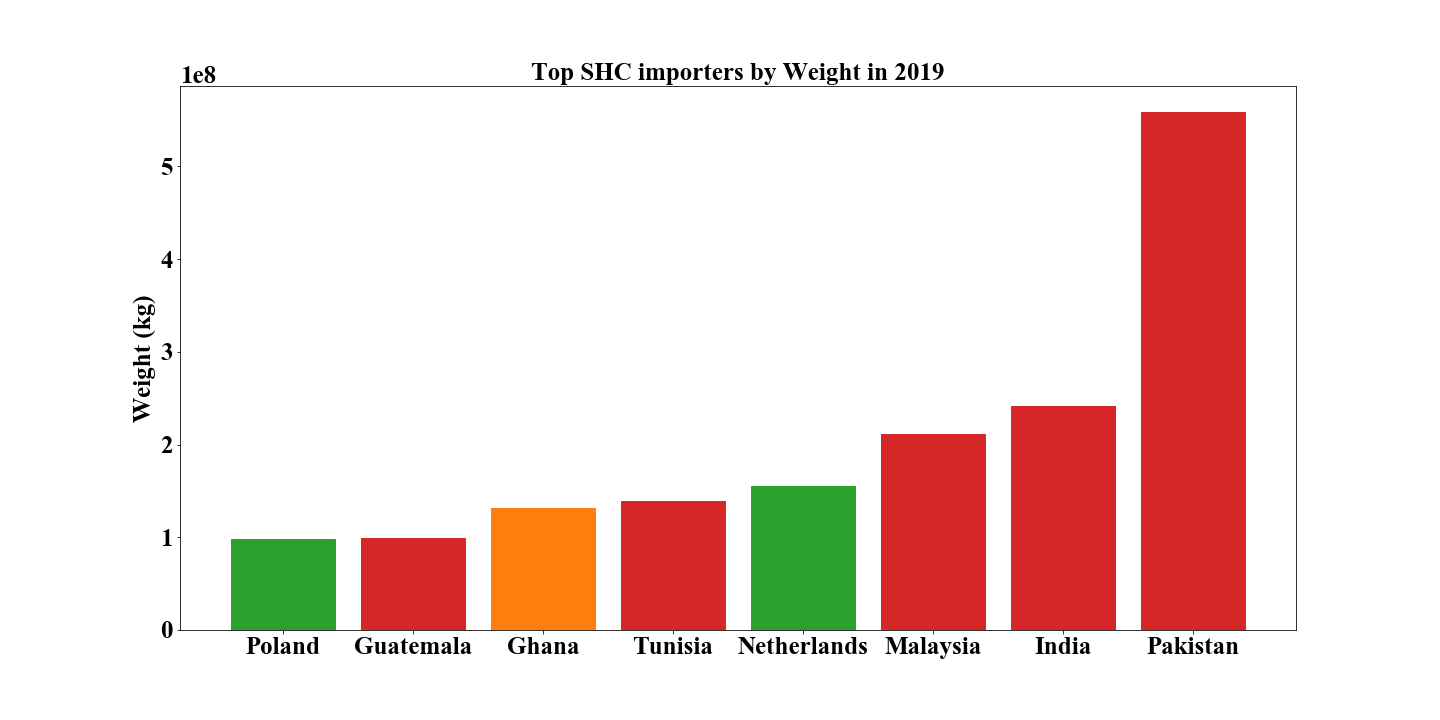

We find that all major exporters are Western countries if you count South Korea as Western. The results might be skewed though since the metric we are using is Trade Value and Western countries have, on average, higher purchasing power. The data for weight is incomplete for exports and we, therefore, can’t use it as a basis for comparisons. Let’s now have a look at the top importers. This time we can use weight as the data is complete.

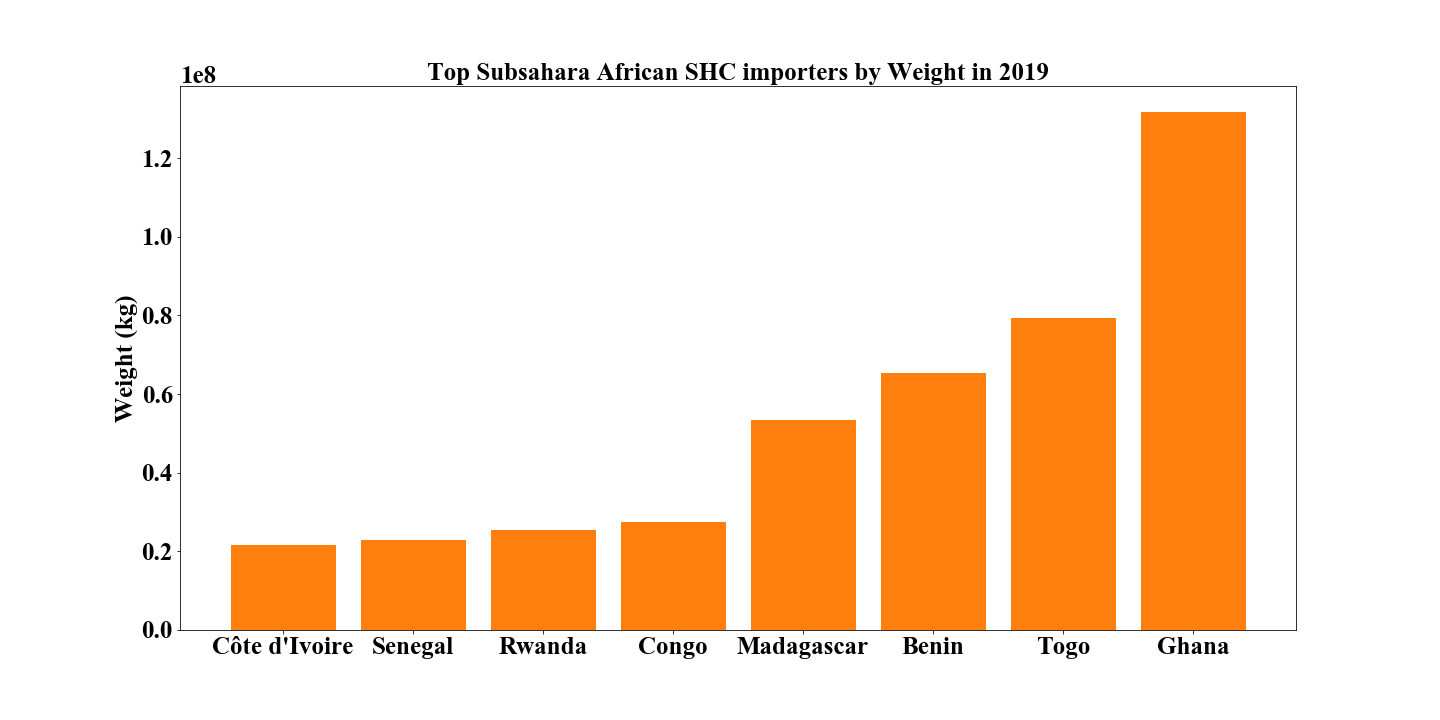

The top importers are Asian countries and in the top 8, we can find only one Subsaharan African country and two African countries in total. Either the scientific and political discussion about SHC seems to overstate the importance of African imports or the picture has drastically changed in recent years. However, if you look at the historical data above, Asian countries have nearly always imported more than African ones. The second hypothesis is, therefore, rather implausible. As a last step, we check out the large players in Africa.

I don’t think there are any major trends to see. There are Eastern and Western African countries represented and I can’t spot any other geographical trends. I’m a bit surprised by the large amount of SHC that Togo imports as it is a rather small country and asking myself why Nigeria is nowhere to be seen as it has a huge population.

While there are some datasets available (as you can see above) there are still problems with the data and the conclusions drawn from them that I want to briefly point out and discuss before diving into the main content.

- There are large gaps in the available data on employment within the textile industry for most African countries which puts high uncertainty on all conclusions.

- Some of the scientific studies that I looked at are waaaay overconfident in their analysis. They extrapolate from three data points to all African nations and they use significantly fewer data to support their conclusions than me in my blog post (sad times for science). To be fair though, around half of the papers and reports are pretty clean and have done a very good job.

- For some reason the scientific discussion about that issue peaked between 2000 and 2010 and the number of papers has decreased in the last 10 years (Might be because politics have reacted or SHC has declined).

- The public and scientific debate is largely framed around African nations even though they are not the largest importers of SHC globally speaking. While there are some smaller studies on India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, I don’t quite understand where this focus on Africa comes from. There clearly are a lot of interesting cases in Africa but if you only consider the numbers Asian nations definitely deserve more spotlight.

These are the reasons why I said that I have some non-negligible uncertainty left about the issue of SHC. Keeping that in mind, however, there are also lots of things we know and can discuss in the following.

Major Considerations

The purpose of this blog post is to not only have a descriptive but also a normative component. I, therefore, want to go through the largest conflicts within the SHC debate and weigh them. Clearly these weighings are biased by my normative beliefs but I will try to justify my conclusions along the way. While the history and data were mostly focused around the economic questions of SHC, there are also questions of culture and the environment that I want to address. I ordered these clashes in decreasing importance that they have in scientific and public discourse.

Economy

When it comes to economic questions, I think that there are three important questions to address. The first is one of causality - if SHC are significantly responsible for the decrease in the African textile industry, bans are potentially justified and I personally should not donate my old clothes. If other reasons are much stronger, SHC probably have more benefits for poor people. The second is one of jobs. I think we can agree on the fact that a net job loss is bad. If most of the unemployed workers in textile production find work in the distribution and preparation of SHC the effect on jobs would not be very harmful. The third question is about the utility of SHC. The access to cheap clothing and thereby the ability to spend more money on food, education, and other goods has to be quantified as well.

1. Causality:

Before 1981 the vast majority of textile production in Africa followed an approach with large state interventions including subsidies and tariffs on foreign imports. However, after two oil price shocks in 1972-1974 and 1978-1981, many African nations accumulated large foreign debt (therefore called the African foreign debt crisis of 1980). To solve these financial problems many states turned to the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In return for their help, the IMF and WB demanded that the nations in question stop their state interventions and open up their markets to international businesses. In the 40 years since African nations have opened up their markets further by decreasing trade barriers. This sudden liberalization might have exposed inefficiencies within the national textile sectors such as power shortages, inefficient infrastructure, or bad logistic networks. Because of this international textile producers such as the US, China, or Southeast Asian (SEA) countries could come in and outcompete local producers. The African economical history in the context of SHC is further explained in an article by the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

On the other hand, you could also argue that the decline in local textile production was influenced by SHC imports from Western countries. The SHC were clearly cheaper, as someone else has already paid for the cost of production and a local producer cannot compete with something that is nearly for free.

While both of these are plausible hypotheses and I think both are correct to some extent, the important question is to which degree they are responsible for this decline. Luckily an economist was kind enough to answer this question with a fairly simple economic model in 2008 already (see Frazer 2008). According to their estimations around 39% of the effects of the decline in local textile production can be explained by the import of SHC. One has to be a bit cautious with these estimates as their model makes some pretty simplifying assumptions but it is helpful as a rough estimate. But it gives us some evidence to assume that the majority of the decline can’t be explained by SHC imports flooding African markets.

Additionally, we can look at other developing countries and how they dealt with similar situations. Many other nations such as India, Pakistan, and many SEA countries have also been large importers of SHC. However, most of them have rather large textile industries providing lots of employment to local people. There are probably differences between African nations and other developing countries - maybe, the latter coped better with the sudden economic liberalization, or maybe their industries didn’t die because it is heavily export-focused, and Western demand for clothes has been steadily rising all the time. But even if there are differences it shows that the decline in local textile production can’t be clearly attributed to SHC and the causal link is actually pretty shaky.

From a perspective of causality, I would therefore conclude that a clear link cannot be established and the evidence doesn’t show it is necessarily harmful to have SHC imports. I would even go as far as to say the evidence suggests SHC is not the major contributor to the decline of local textile industries and they would have suffered regardless even if there were no SHC imports.

2. Jobs:

While a decline in local production leads to fewer jobs in the textile sector, we also have to look if and where these people are re-employed. According to Karen Hansen (Hansen 2004) in Rwanda, 88% of the people who lose their job found new opportunities in the handling, cleaning, repairing, and restyling of SHC. Additionally, she reports that the jobs in the SHC industry provided on average higher earnings than tailoring or other forms of production. So the people who found new work profited on average from SHC. We have to be a bit careful with the generalization of this claim as Rwanda is only one small country and I couldn’t find similar statistics for other African countries. However, the underlying reasons seem to broadly make sense to me. If you have been trained in tailoring or distribution of locally produced clothes it is only a small step to prepare and distribute SHC. Most of the steps in the production and distribution chain seem to be similar between both industries and if the demand stays equal but the local supply declines it is likely that more jobs in the SHC industry are created that one could switch to. To be honest I don’t quite understand why the jobs in the SHC industry provided higher average earnings and I would not expect this effect to generalize to other countries until this trend is established through empirical data or an analysis of the underlying reasons.

From an employment perspective, local production seemed to provide slightly more jobs than SHC but given that the domestic production might have failed independent of used clothing imports the SHC industry might have actually been a lifeline for many and thereby net positive when it comes to jobs.

3. Utility of SHC:

What we shouldn’t forget is the large benefit that SHC does provide to many consumers in Africa. It is important to note here, that SHC are not free most of the time. Most of the SHC actors are private enterprises that want to generate a profit but even NGOs charge a price most of the time. Most NGOs don’t own the entire chain from their local chapter over the shipping and the local distribution but rather only parts of it. Therefore their goal is to break even on all the parts that they don’t own which means hiring local distributors or transport companies. Keeping that in mind, SHC still are the cheapest alternative for clothing out there. The cost of production has already been paid for by Western consumers and the price can therefore be lower. Additionally, they still have to compete with companies that sell new, unused clothes and have to undercut them by a significant margin to make up for the fact that they are used. This margin can be spent on more clothes, education, or just saved for a worse day and thereby provide value to many many people.

I, personally, would rate the positive effect of cheaper products for hundreds of millions of people higher than the potential job losses discussed previously. But since the question of jobs is not very clear at all and potentially speaks in favor of SHC this weighing doesn’t really apply here.

A thing that I will look out for is the development of the textile industry in Rwanda. The ban was a pretty bold move potentially costing them millions of dollars in foreign aid and other support but so far the country has seen some rise of local textile production. Whether this was a smart move or not will be unveiled in the next couple of years but it is definitely a stress test for traditional economic theory.

Culture

The question of second-hand clothing is not only economic but also one of culture and tradition. While SHC destroy local clothing traditions they also provide the opportunity to access Western culture cheaply. I want to present and weigh both views in the following.

-

Protecting existing cultures: A decline in domestic industries means that local producers, designers, and artists have less influence over what is worn locally. While local production is usually guided by local traditions and thereby preserves cultures that have survived for thousands of years imported clothing and SHC do not. These clothes are usually produced for Western consumers and therefore influenced by Western culture and designed by Western designers. Some countries frame the question of SHC not around economics but rather one of protecting local heritage. Especially Rwanda frames their tariffs (de-facto bans) of SHC around a narrative of dignity. They don’t want to be the dumping ground of Western powers but rather lose their colonial chains and produce clothing that reflects their cultural heritage.

-

Accessing new culture: While there are large cultural narratives of heritage and tradition there has also been an increasing influence of Western culture throughout Africa. Many people watch Western films, are fans of Western football clubs (which show Western ads), or have positive attachments to Western cultures for other reasons. While most Western clothes are financially inaccessible to the average African consumer a second-hand version isn’t. A Hugo Boss or Tom Taylor T-shirt doesn’t cost 50€ anymore but is traded for a tenth of the price or less on local markets. Since this is a sign of wealth and status for many individuals I think it is generally meaningful to have access to Western branded clothing.

How you weigh these two views is very dependent on the individual person. For many people, traditional values give important psychological benefits such as a sense of identity or a sense of consistency in their life. For others, on the other hand, the status symbol or the sense of belonging to a more globalized generation is equally as important. I don’t have any intuitive sense as to how important these two factors are to the majority of people and the comparison is additionally complicated by different regions (e.g. compare rural Rwanda with Lagos) and other confounders. I’m inclined to favor the cheap access to new culture, since a) African demographics are heavily skewed towards young people who are often less traditional and b) people who have strong preferences for traditional clothing can probably access this for less than another person could access original Western clothing. However, I am rather uncertain about this trade-off.

Environment

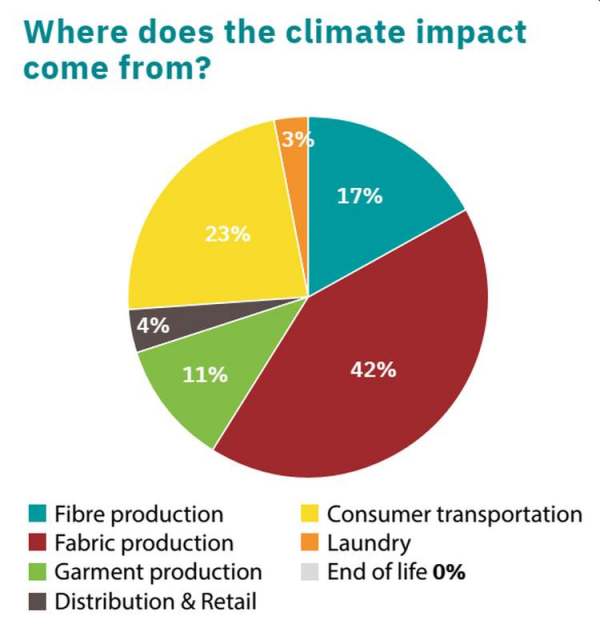

It is often pointed out that the textile industry in general has a rather large carbon footprint. A logical consequence of this is that shipping SHC from Europe or the US to African countries would increase that footprint even further and therefore increase global CO2 by a significant margin. However, this conclusion is premised on the fact that transport is a major contribution to the CO2 footprint of the textile industry. In reality, though, transport contributes only 23% while fabric production is the most CO2 intensive with 42% of the overall footprint.

If you additionally consider that most clothing is produced in SEA and transport distances are only half as long if you ship to Africa, the CO2 impact from SHC is rather marginal. This might be different for other countries but transportation should never be the major contributor of the clothing carbon footprint. Donating to a charity that distributes only in your own country or to a local thrift shop would obviously provide zero CO2 emissions but it would also deny many significantly poorer people access to cheaper clothes. Since there are significantly more old clothes in the West than is demand for SHC donating to poorer nations definitely is a net gain for the environment. Overall, there is just not a large footprint from clothing transport and it seems to have only a small effect on the overall weighing to me. If the alternative isn’t donating locally but throwing old clothes away, there is substantial damage to the environment since it means new clothes are unnecessarily produced.

Reactions and Alternatives

The problems associated with SHC have been known and researched for a long time and both policy-makers and NGOs have reacted to some extent. The EU has written a white paper/consumer briefing in which they, among other things, promote circular fashion. This concept, as far as I have understood it, essentially just says that clothes should be made out of materials that are easy to recycle or re-use. While this shows good intentions I think its impacts are rather minimal. A report about exports of SHC from Nordic countries provides guidelines for exporters and policy-makers such as nurturing long-term cooperative relationships with local African NGOs or distributers or assisting the developing countries if they need help on a state level.

NGOs have also reacted to the accusations. An Oxfam report addressed the problems with pretty solid analysis already in 2005. They also concluded that SHC is largely not a large causal factor in the decline of domestic clothing manufacturing and give explicit guidelines to mitigate potential harm. These include sending SHC primarily to very poor countries with small textile industries as they benefit the most or respecting the right of countries to protect their infant industries. This mostly means double-checking who you cooperate with as some private distributors are very active on the black market. Additionally, there are regional NGOs such as the Kleiderstiftung in Germany that cooperates with local African NGOs in their distribution and never use private partnerships along the process. While their methods might not be as efficient as the free market their prices are probably still cheaper since they have no profit incentive and are subsidized by Western donations. The advantage of these end-to-end cooperations is that a local buy-in is ensured and the NGOs are not seen as ‘dumbing old rags’ but rather providing help for people who need it and, importantly, want to be helped.

Conclusions

When should you not donate: If my research is correct there are no strong economic reasons not to donate. You will likely not destroy local industries but help people in need. The only reason that I see for not donating is if you think that local culture should be preserved at all costs (even against the will of locals). However, if you choose not do donate, bear in mind that this has a cost. Your action has likely denied people in need access to cheaper clothing or access to Western culture. It might also not save local industries as they are outcompeted by Chinese manufacturing anyways. If you have a strong desire to preserve local clothing culture I suggest donating to certain NGOs or buying traditional African clothes. Since you are probably a person from the West your purchasing power is significantly higher and you can afford to pay a high premium which cross-subsidizes domestic African textile industries.

When should you donate: If my research is correct I would recommend everyone donate their old clothes. The economic weighing seems to favor donating pretty strongly and the cultural question is mildly in favor of donating. From an environmental perspective, it makes sense to donate your clothes as well. Additionally, the cultural questions seem to have too high uncertainty attached to them to justify a clear call against donating and the environmental impacts seem marginal at best. I would therefore weigh the economic question significantly higher than both others combined. Especially, since there are regulations in place and there exist NGOs that address many of the problems of SHC I can only recommend giving away your old clothes and helping someone in need.

One last note

I would like to thank Maria for her feedback and having the idea for the blog post in the first place.

If you want to get informed about new posts you can subscribe to my mailing list or follow me on Twitter.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.