What is this post about?

Whenever I ask people why they smoke I usually get an answer along the lines of “It sometimes helps with stress. I know I shouldn’t do it. I’m trying to stop.” But sometimes they then add something like “The taxes generated through cigarettes are so high that they can easily pay for my lung cancer” or “But it is actually good for the health care system as a whole because I will die younger and therefore cost the system less”. Possibly these thoughts were inspired by comedy videos such as Yes Minister - on smoking but I find both answers intuitively implausible but neither they nor I had looked at the data.

Therefore, I want to do four simple things in this post. First, give a basic overview of the statistics behind smoking, e.g. demographics or magnitude of the global tobacco industry. Secondly, analyze the taxes vs. cost of diseases argument. Thirdly, investigate the question of whether people save the state money by dying younger. And lastly, present miscellaneous considerations that are not directly related to the previous ones but are still important such as the costs of passive smoking or possible ways to reduce smoking.

As always, if you disagree with my approach, with my analysis, or with my conclusions, don’t hesitate to contact me. If you like it and know other people who you expect to like it too, share it with them.

DISCLAIMER: this is not a research paper. While I read a lot of other people’s research it doesn’t have the rigor an actual scientific paper would require. It should be understood as the summary of 50-100 hours of research done by someone who is interested in a realistic unbiased answer to the question and likes number crunching.

If you want to play around with the code yourself or have access to the figures you can find them on GitHub.

Summary of the Results:

In order of perceived importance my conclusions are:

- To a large extent calculating the cost and the revenue of smoking-related illness is just an exercise in creative accounting. Especially when the people who estimate the numbers are ideologically motivated, e.g. a libertarian think tank arguing for smoking or anti-tobacco groups arguing against it the numbers tend to be either pretty clearly for or against it. Even in the cases where non-ideological actors such as scientists make an honest effort to estimate the true number it is still very hard. For example, some diseases appear more often in people who smoke but might just be a result of their socio-economic background and thus not causally related to smoking. Disentangling these and many more factors is quite hard, if not even impossible given the current data. Thus I have very high uncertainty in my estimates.

- Putting the complexity aside my best estimate is that smoking is a net negative for the state in the vast majority of cases.

- My methodology underestimates costs and overestimates gains from smoking. Since the scientists are usually concerned with rigor they often only include those diseases that are very certainly related to smoking, thus undercounting the true cost. Furthermore, there might be relationships that we don’t understand yet underestimating the true costs even further. The gains from premature deaths on the other hand are likely an overestimate since I used average estimates for pensions even though smokers tend to be disproportionally from lower-income backgrounds. Thus the figures presented might be slightly deceptive if you ignore the error bars.

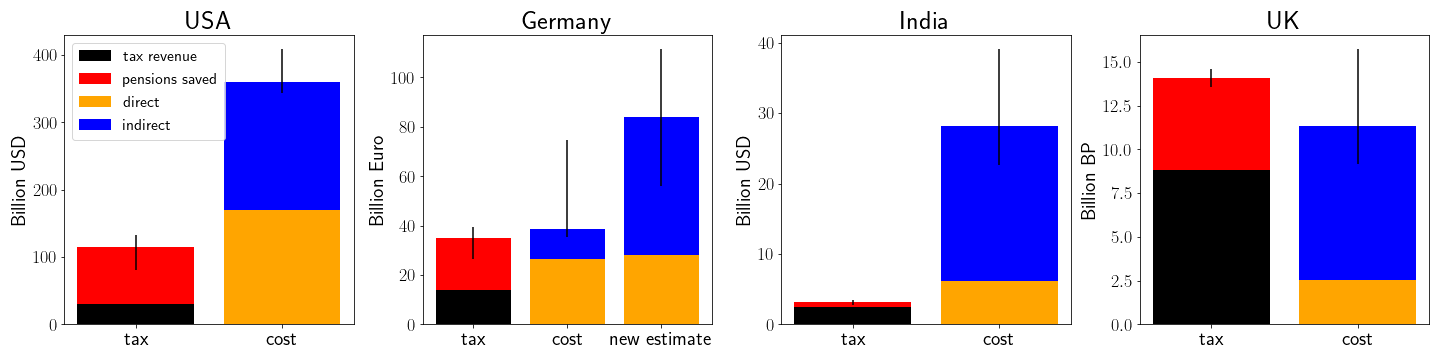

- The income from smoking does mostly not come from tax revenue but rather from the pensions and health care saved from premature deaths. Essentially, the entire reason for why this argument might have a chance at all is because old people are expensive for a state and cigarettes tend to kill them earlier. Thus I conclude that for countries with pyramidal demographics, e.g. many developing countries the cost of smoking is much larger than the potential gains. For countries with less pyramidal demographics, I would estimate that smoking is on average still a net negative. However, there might be specific circumstances that make it possible that the cost averted outweighs the harm inflicted on a financial level. This calculation does not include the emotional harm of lost family members or other loved ones though.

- I would still heavily advise people and states against smoking. On a personal level, trading some instant stress relief for 10 years of your life and a significantly increased risk for many really nasty diseases seems like a bad value proposition especially because the advantages of nicotine can also be accessed without the harms of smoking, e.g through nicotine gum. On a societal level, there are many people who are harmed through passive smoking while never having the chance to opt out of that relationship because they are vulnerable, e.g. children or elderly family members. I think those who are innocent and don’t consent to this lifestyle should be prioritized over your personal right to self-harm. I am aware that it is very hard to quit and it is an uphill battle but there are many organisations and people who can help and make this journey easier.

Some basic overview Statistics

Most of the overview statistics come from Our World in Data. Fortunately, they have already compiled a fantastic overview and I merely selected the parts that I found most important. If you want more charts go to Our World in Data - they are fantastic as always.

If you read the post on your phone you can activate desktop mode to zoom into the figures.

Prevalence of Smoking

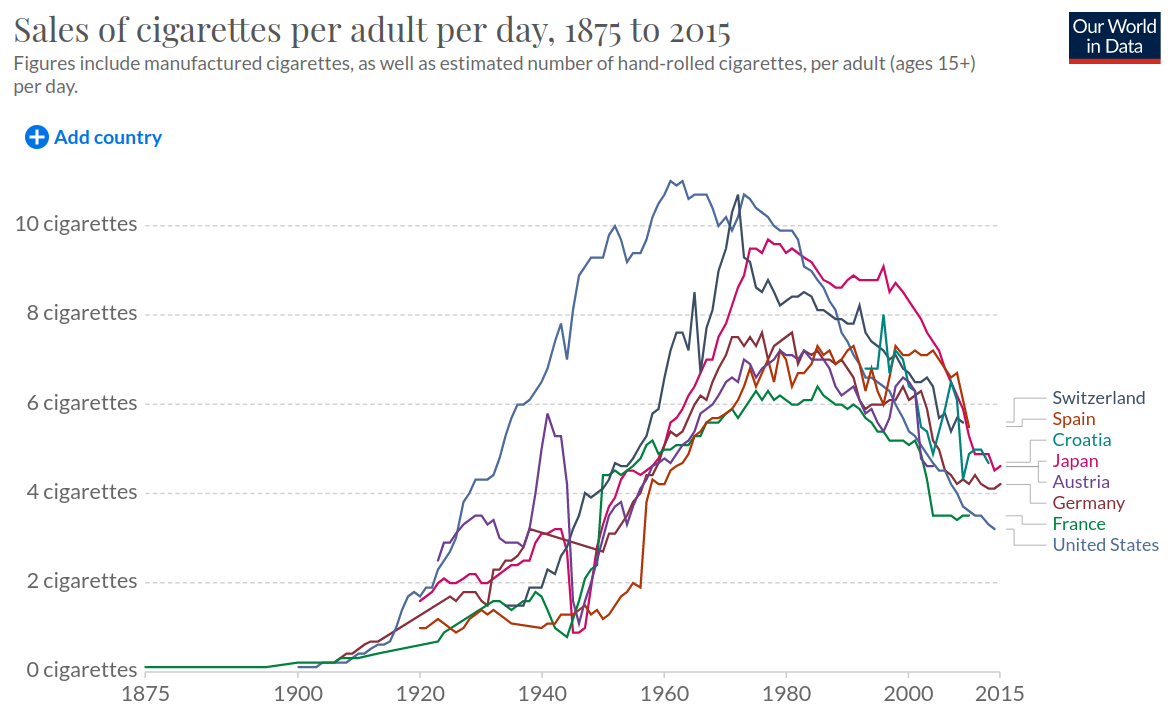

The sale of cigarettes has probably peaked around 1980 in most developed countries. However, the historical data is not available for less developed countries so it’s impossible to put their current number into a historic perspective.

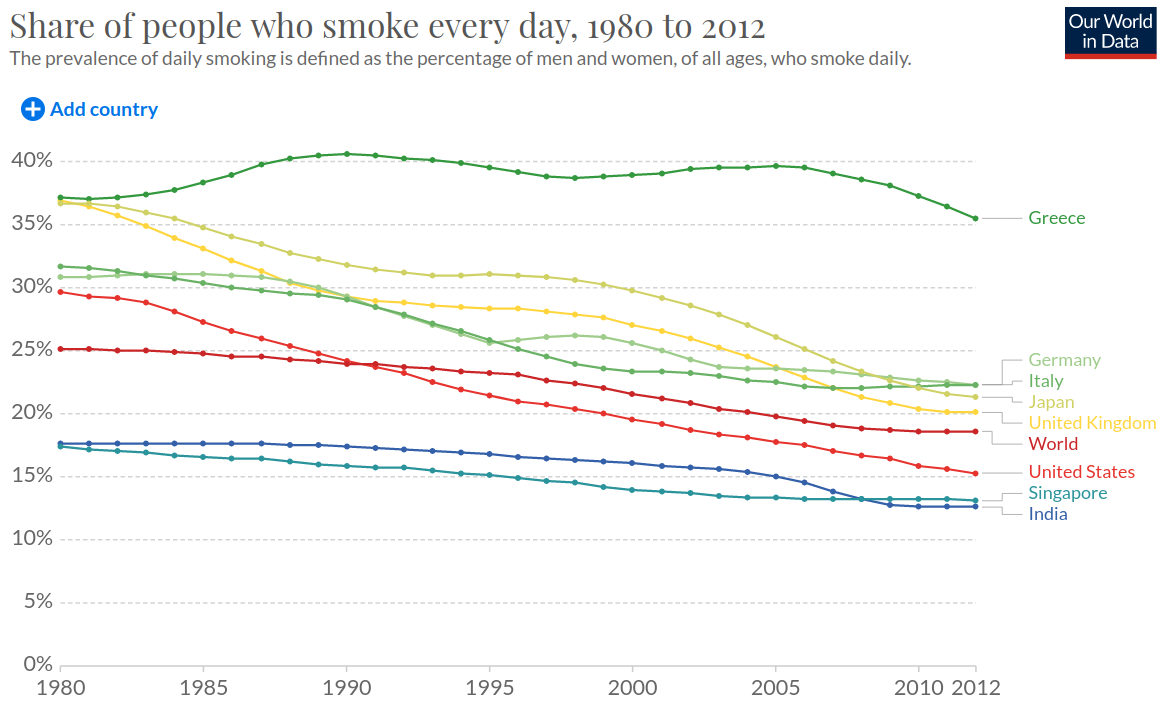

Looking at the share of people who smoked every day from 1980 to 2012 we find that there is a slightly decreasing trend for the entire world.

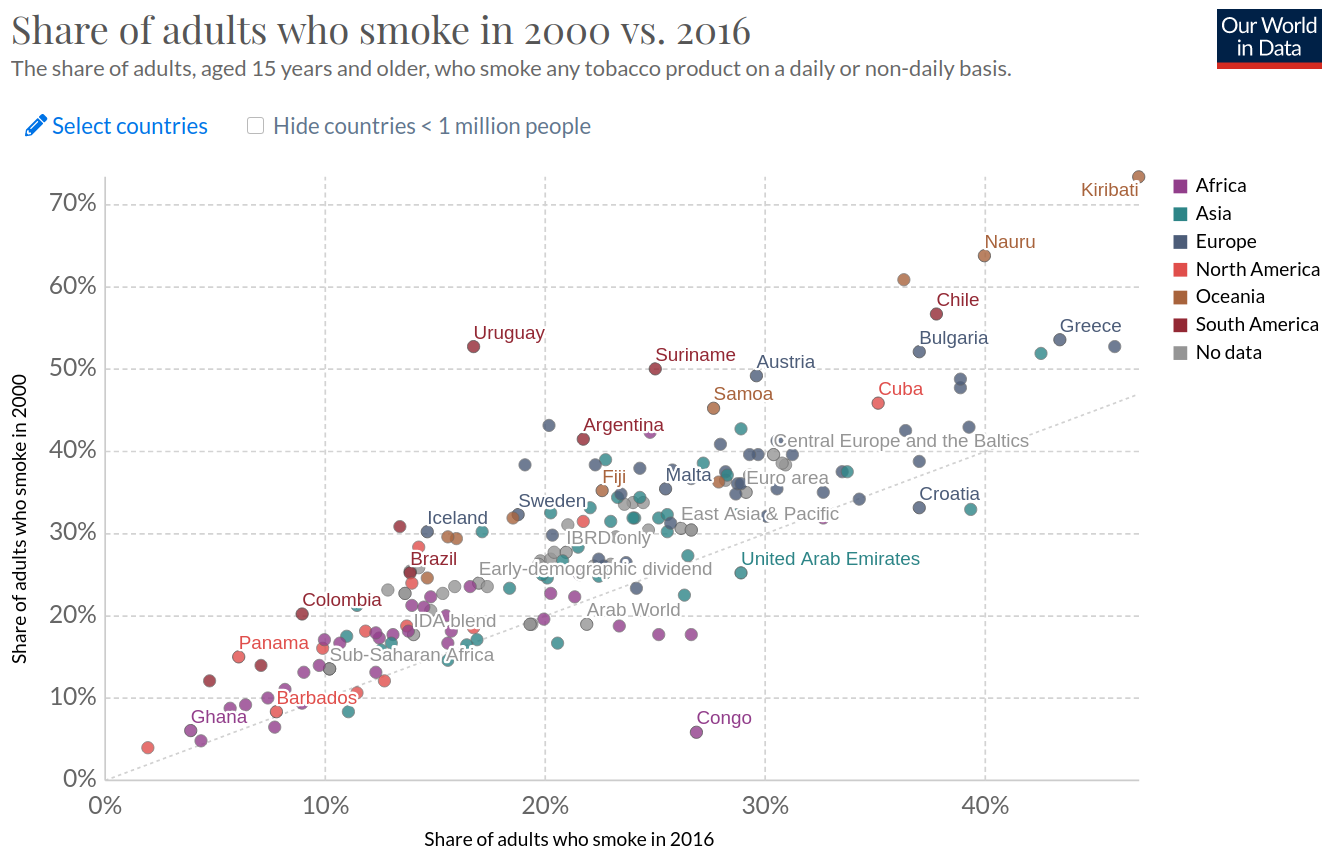

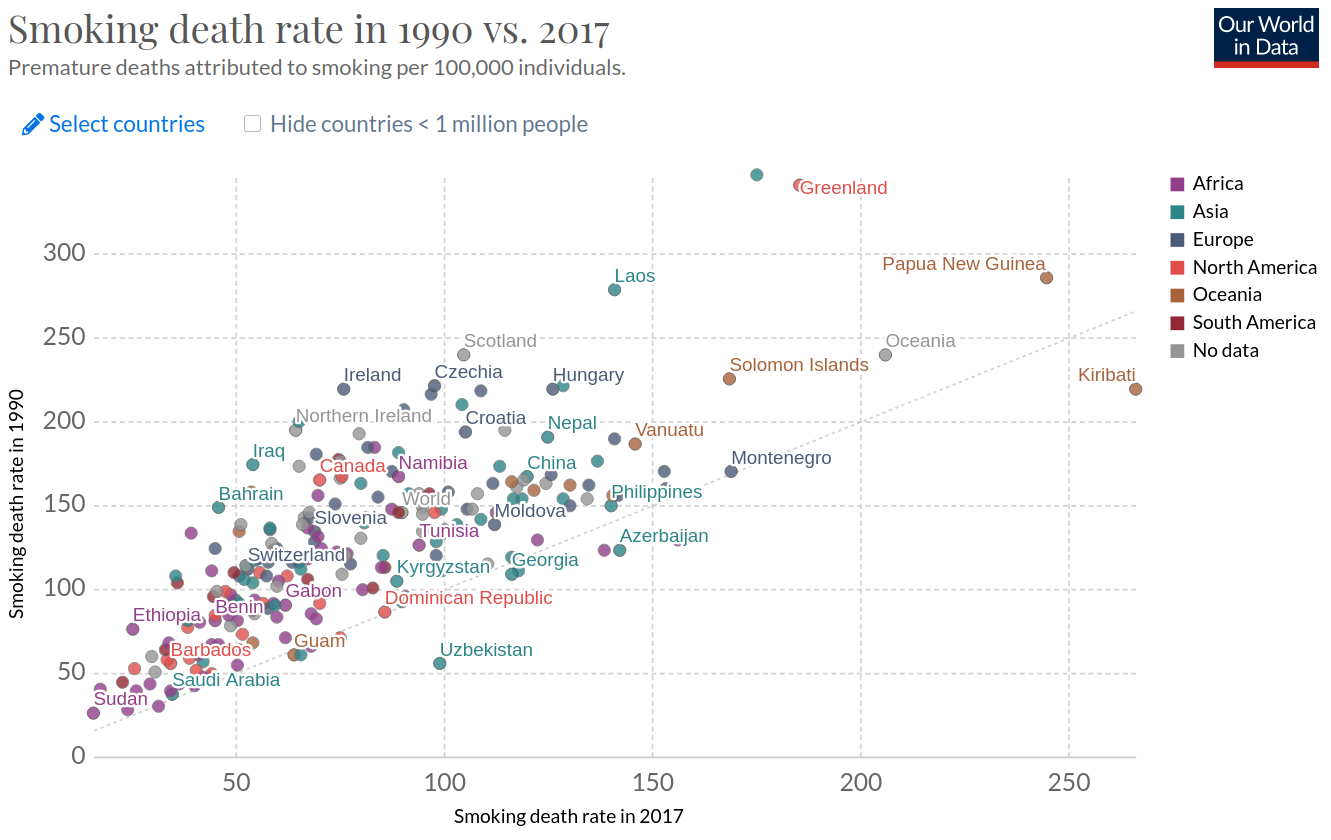

When comparing the proportion of adults who smoke from 2000 with that of 2016 we find that there is a decrease of smokers for the vast majority of countries in the world (above the diagonal means decrease).

Even though the trend is decreasing it should not be forgotten that the absolute numbers are still pretty large. Overall, within all major regions of the world 15%-35% of the population smoke on a daily or non-daily basis.

Influence of Region

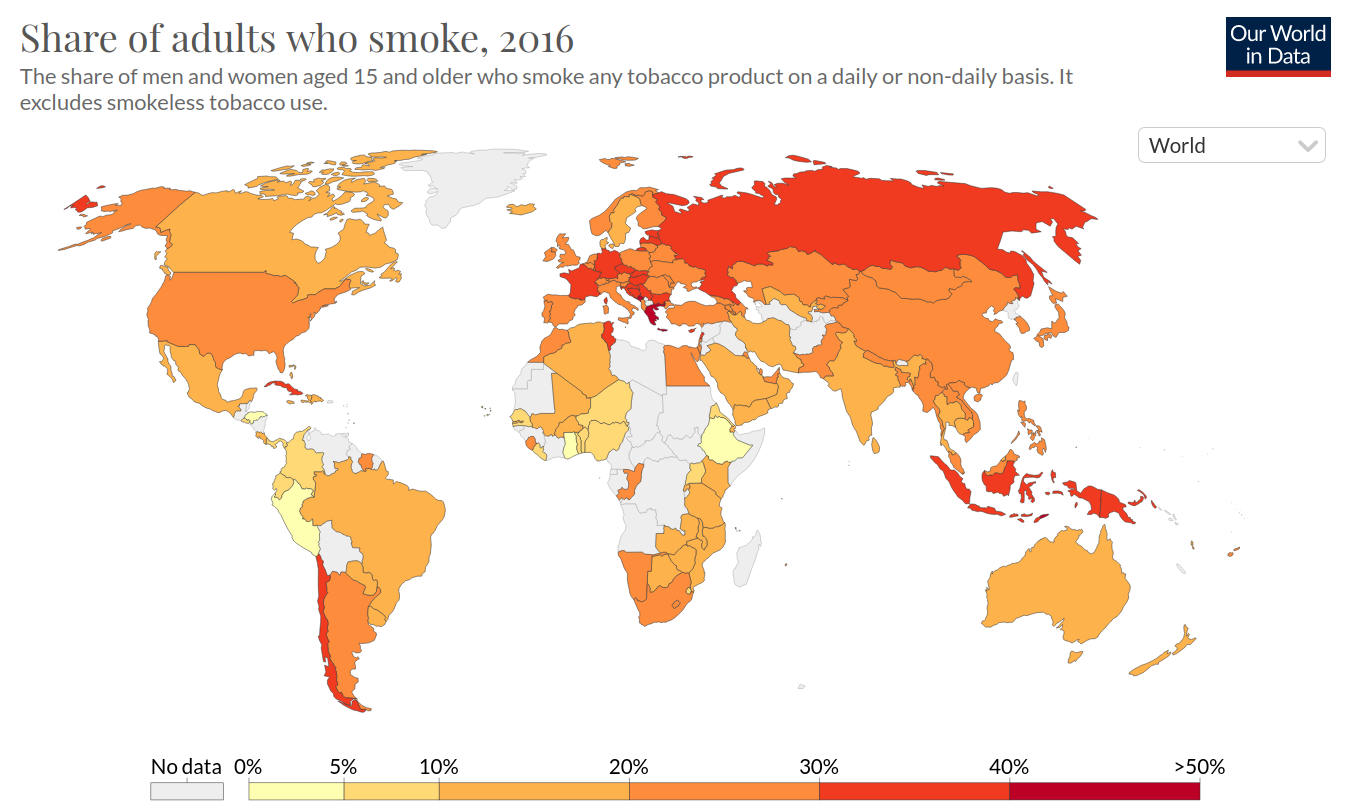

Looking at the share of adults who smoke in 2016, I don’t think a clear pattern can be established. One could argue that there is a larger number of smokers in Europe and parts of South East Asia but I would be careful not to overinterpret these trends.

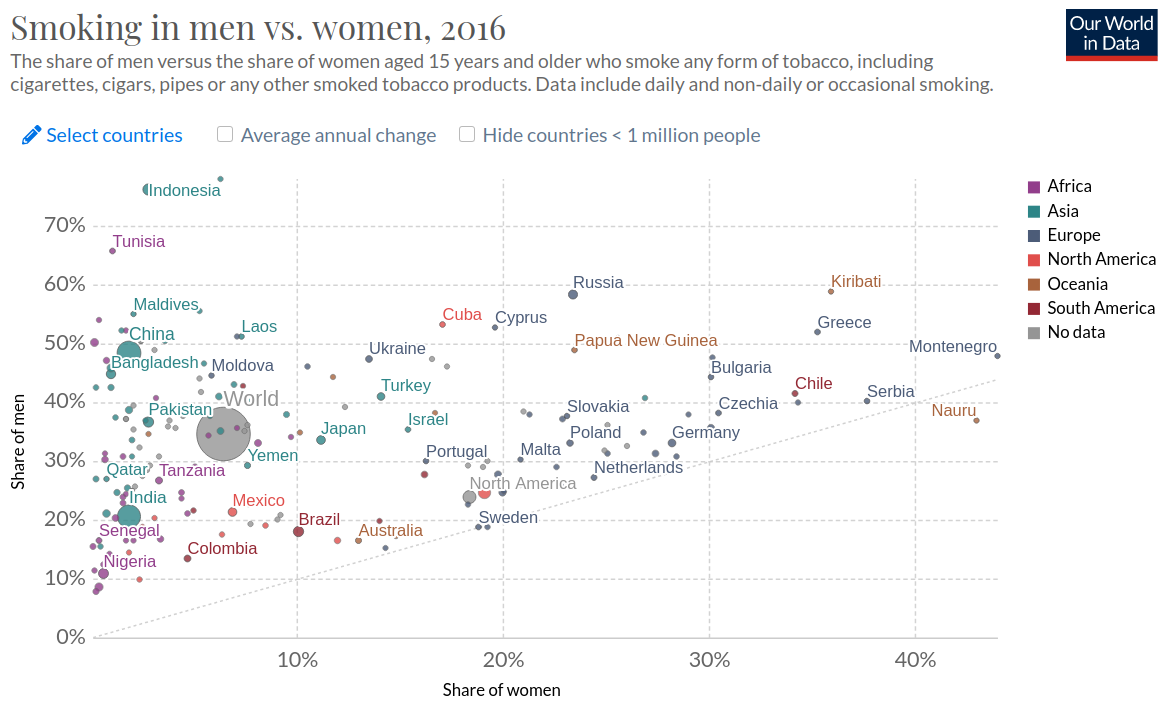

Influence of Gender

Nearly universally women smoke much less than men. It also seems like this effect is stronger for less developed countries.

How bad is Smoking?

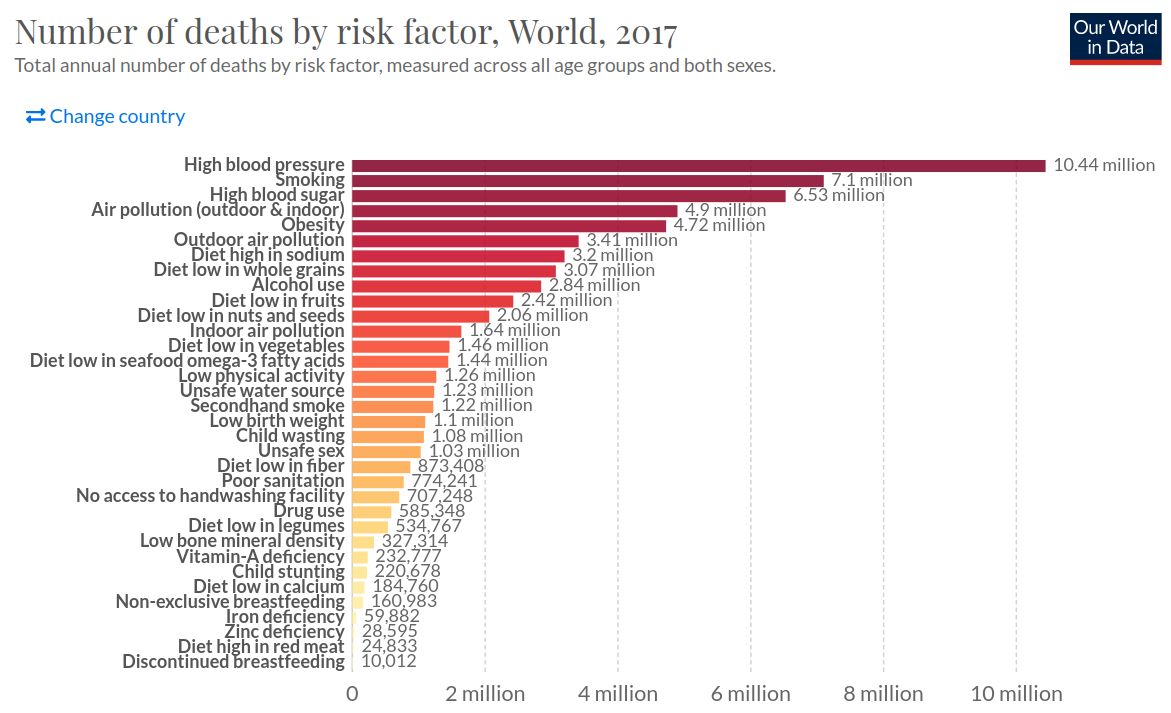

Smoking is worse than I expected and I already expected it to be quite bad. Looking at the number of deaths by risk factors in 2017, smoking was in second place with 7.1 million deaths.

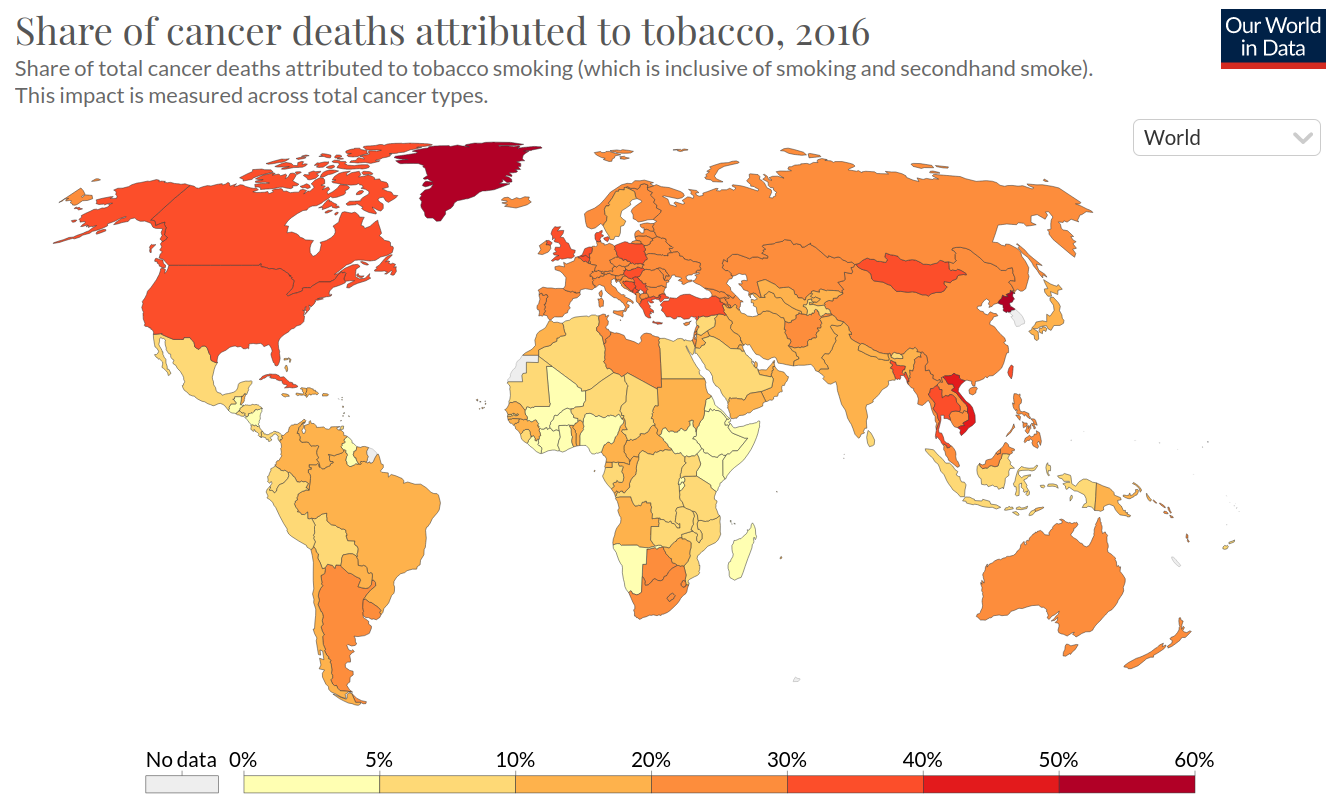

We should also take a closer look at the diseases associated with smoking. Let’s start with the most obvious one - cancer. This is the share of cancer deaths attributed to tobacco in 2016.

Given that there are so many different kinds of cancer, I find it remarkable that between 5% and 50% can be traced back to smoking depending on the country.

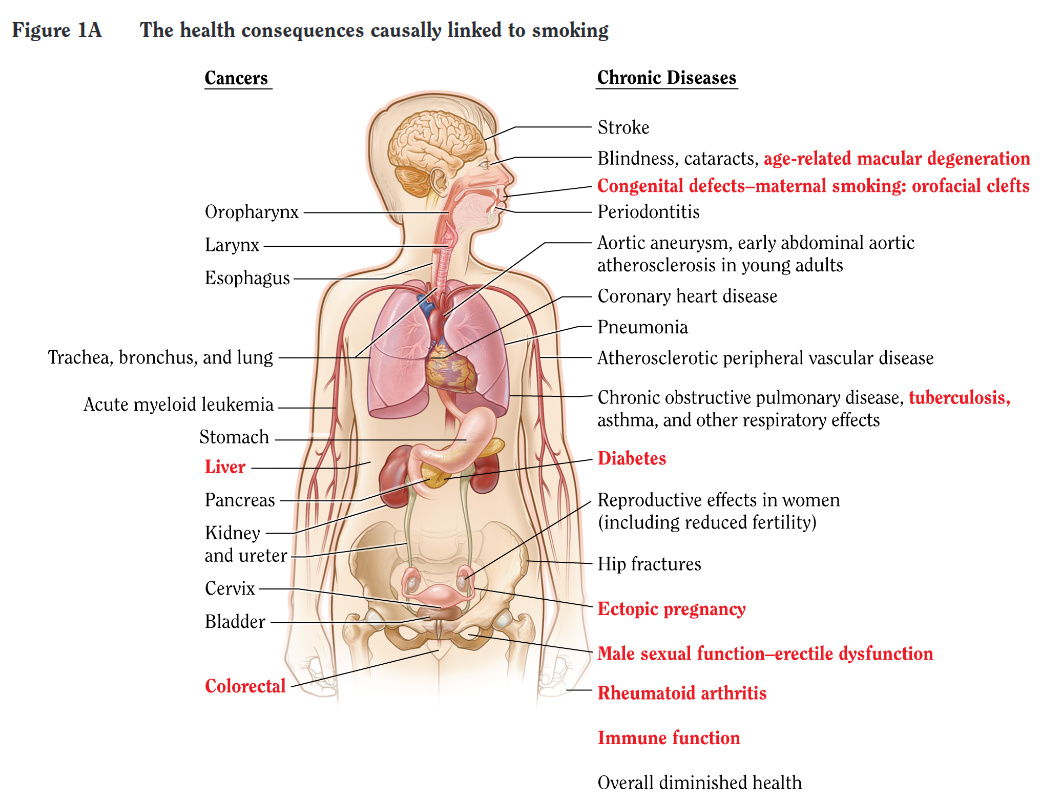

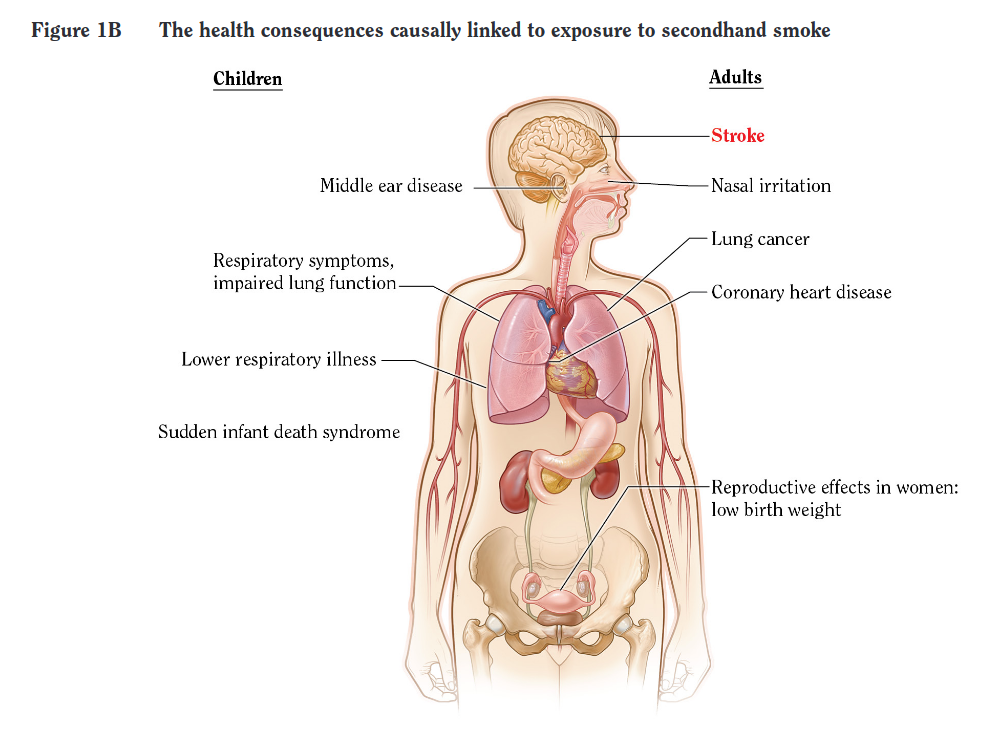

A report by the Surgeon General breaks down the diseases which have been linked to smoking. The diseases in red have been causally linked to smoking while the others have different degrees of correlations with smoking and are thus weighted accordingly in the estimation of costs. It needs to be pointed out that this report is from 2006. Since then our understanding of smoking-related diseases has increased and the figure might include more causal links and more diseases.

While all of this sounds pretty bad it needs to be pointed out that the overall number of tobacco deaths is decreasing over time. My guess would be that the science is slowly winning against disinformation campaigns and advertisement and governments increasingly put smoking restrictions on the agenda.

The Tobacco Industry

According to Statista the global revenue from cigarettes was $678 billion in 2020. The largest markets were China ($225.5 billion), the USA ($78 billion), Indonesia ($25 billion), Russia ($24.4 billion), and Germany ($24.3 billion). The global cigarette revenue is around 2.5 times as much as Apple’s revenue in 2020 ($274.5 billion). The industry is larger than I expected. I think this is because I’m in a social bubble where nearly nobody smokes.

Now that we have a broader overview of smoking in general we can dive into the two main questions of this post.

1. Taxes vs. Costs of smoking-related Diseases

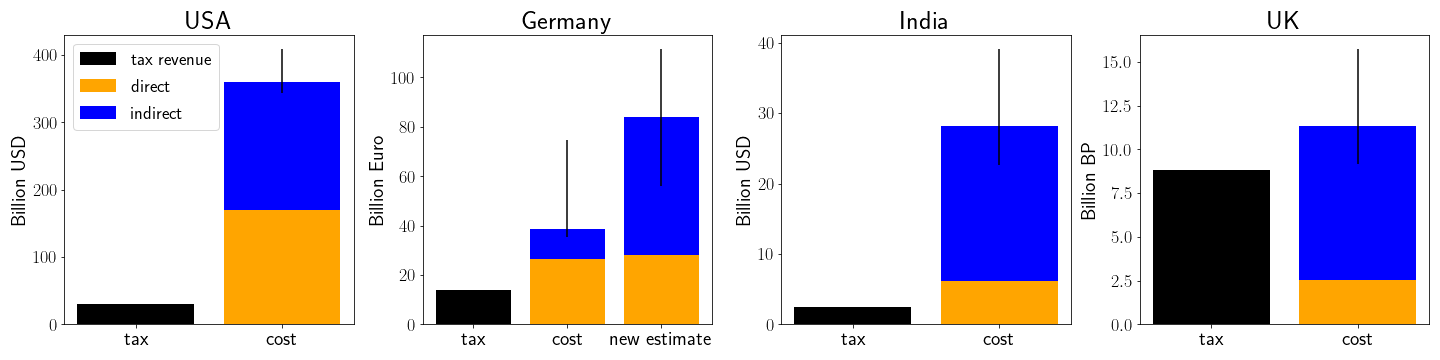

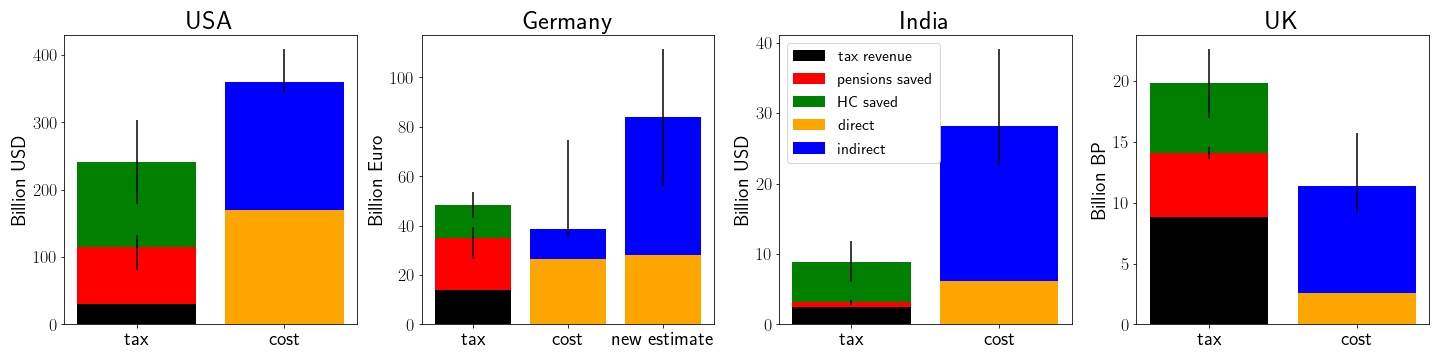

While the tax statistics are available for most countries, the cost estimates are not. Thus I pick four countries for which I could find most numbers I’m interested in to get a feeling for the question. These are the USA, Germany, India, Germany, and the UK.

There are multiple ways in which states can tax cigarettes. For instance, you can tax the import of tobacco and the sale of cigarettes. But no matter at which stage of the production chain the state taxes cigarettes it will ultimately gain some revenue from the production and sales of cigarettes. This revenue is not at all negligible. According to this Statista report the tobacco tax revenue for the USA was 17$ Billion in 2010 and 12 Billion in 2020. According to a WHO report Germany earned €14 billion in taxes in 2018 and the UK earned 8.8 Billion British Pound. However, the WHO count combines specific taxes and ad valorem (e.g. Value-added) taxes whereas the Statista report only reported specific taxes. Thus the WHO report estimates the US tax income due to cigarettes on $30 Billion in 2018. The same report states that India earned 183.3 Billion rupees in taxes from cigarettes which corresponds to $2.5 Billion. While this is a lot of money it needs to be compared to the cost to the public health system in each country respectively.

According to a report by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) smoking-related Illnesses cost the USA 170$ Billion per year in direct cost. According to the original study this translates to 8.7% of the entire annual health spending of the USA in 2010 with a 95% confidence interval between 6.8% (i.e. 133$ Billion) and 11.2% (i.e. 219$ Billion). Accounting for inflation these values become $153.2 billion, $195.9 billion, and $252.3 billion in 2018 respectively. On top of the direct cost, the report estimates that there are 156$ Billion in lost productivity due to premature inability to work in 2006 or $194.4 billion in 2018 accounting for inflation. The lost productivity is estimated directly through the present value of future earnings, e.g. taxes, but also from more indirect measurements such as foregone future imputed earnings from unpaid household work that is unrealized as a consequence of early mortality. The exact estimations for indirect costs vary between countries and studies but they broadly include these direct and indirect estimates.

Doing similar estimates for the other selected countries yields a direct cost of €16.6 billion for Germany (see study). Importantly, this study uses data from 1996 whereas the tax income is from 2018. Thus, accounting for inflation, this estimate would be €26.6 billion in 2018. Furthermore, this is an underestimate since they only approximated the cost of the four most common illnesses and ignored the less common ones. They also didn’t estimate the opportunity costs of lost productivity. A different study estimates that in the year 2003 Germany lost €8.8 billion due to work loss days and early retirement linked to smoking. After accounting for inflation this estimate would yield €12 billion in 2018. However, this is likely an underestimate of the true costs as they are very conservative with their estimates of lost productivity. Furthermore, a newer estimate of the tobacco atlas claims the cost in 2015 to be €79 billion splitting into one-third of direct and two-thirds of indirect costs. Accounting for inflation this yields €28 billion in direct costs and €55.8 billion in indirect costs.

A WHO study from India concluded that they bear costs of INR 1773.4 billion ($27.5 billion) per year with estimates from 2017. They split into 22% (i.e. $6 billion) direct and 78% (i.e. $21.5 billion) indirect cost.

A report by the UK government states that smoking costs the UK approximately 12.6 billion British Pound, which consists of 2.5 billion in direct cost, 1.4 billion from social care and 8.6 billion due to lost productivity. Thus the UK is the only country that makes more money from taxation than it has costs from direct harms. I’m not an expert on the NHS but I would speculate that these lower costs compared to other countries come from the fact that the UK applies cost-benefit calculations much more strictly to health than other countries. If, for example, a treatment costs more than 30,000 pound per QALY then it is very unlikely to be paid for by the NHS (see section 6.3 here).

Looking at the summary plot above, I would argue that the argument is not very convincing in most contexts. In the US, Germany, and India already the direct health costs from smoking outweigh the entire tax revenue gained from it. In the UK, I would be more open to the argument of “smoking for your country” but it still seems rather inefficient. The Queen would probably prefer if you just kept working until you died instead of dying early from smoking or became a skydiver at 65 ;)

2. Dying Younger to save the State Costs

As far as I understand the argument correctly it goes: “Old people cost the health care system much more than younger people. Additionally, the state pays pensions after a certain age is reached. Both costs would be reduced if people died exactly after they stop working.”

Before looking at the data, I would expect the argument not to hold true. My understanding is that the cost for the healthcare system mainly increases around 2 years before a person dies. Since the smokers just die earlier this cost is probably not reduced by much and rather just shifted. I would even expect the opposite to hold true, i.e. that smokers cost the health system much more in their last 2 years than non-smokers. While it is true that pensions are costs for the state I would assume that most people are unable to “time their smoking death correctly” and die quickly at age 65 of spontaneous lung cancer. So usually it will be a long process that often means they are unable to work before their pension age. Thus they are not only a burden for the system but additionally create opportunity costs due to their lost productivity. The direct cost for the healthcare system and the indirect cost for society are already estimated in the previous section. Thus in this section, I will only focus on the money saved by the state from pensions and health care.

The Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), a liberal economic thinktank in the UK estimated exactly this number in a report in 2017. They compute the amount of money saved due to premature deaths from smoking-related illnesses. Their calculation includes the death rates per age-bracket multiplied by the cost of saved pensions and health care. They estimate that the UK saves 9.8 billion British Pound annually due to premature deaths related to smoking. I think their estimate is influenced by their ideological affiliation though. Their numbers on lost productivity are very conservative estimates and thus much lower than the 8.6 billion estimated by the British Government. For example, they only compare the direct income due to taxes with the cost of education and health care but don’t include the indirect savings through unpaid labor such as raising children or taxes paid by the employer of that individual.

Because I think the report is biased, I will do a separate analysis. I originally wanted to repeat a similar strategy as the IEA report, i.e. combine age-specific population estimates with age-specific death rates from smoking and then compute the resulting saved pensions. However, I encountered two problems. Firstly, the publicly available data on age-specific death rates from smoking are insufficiently fine-grained to get an estimate that doesn’t have huge uncertainty attached to it. Secondly, I found it very hard to include counterfactual death times in my calculation. I could, for example, imagine that someone who dies very early due to smoking-related illness would not have reached the average life expectancy of their country because they have other conditions that potentially interact with each other such as alcoholism or obesity. Since there is no data publically available on the conditional life expectancy for these groups (even though they seem to exist somewhere as the US Surgeon General report claims to include them in their estimate), I think my model would have been fancy but probably pretty wrong.

Thus I decided to use a simpler, more back-of-the-envelope style, calculation that yields a likely upper bound for the true saved costs. There are multiple sources that claim that smoking reduces your life expectancy by about ten years (see e.g. here or here). They control for factors such as income, socio-cultural background, nutrition, etc. such that my concerns about the counterfactuals are at least reduced. An estimate of the number of smoking-related deaths per year is publicly available for all four countries in question and average pension numbers are public or can be roughly estimated. This strategy has some pathologies as it ignores the age-distribution of people dying.

For the USA it is estimated that 480,000 people die per year due to smoking-related illness (see CDC), for Germany this number is 121,000 (see here), for India it is 10 Million (see Wikipedia), and for the UK 78,000 (see NHS).

Estimating the pensions per country is not straightforward as most of them are complex and depend on a lot of different factors such as whether you worked for the state or private industry, whether you have children, whether you are widowed, and so forth. However, in most instances, you can find the average pensions per person or at least estimates for these numbers. In the USA, multiple websites (e.g. [1] or [2]) report that the average pension in the USA for 2021 is $1,543. In Germany the number is reported to be €1495 (e.g. [3] or [4]) in 2020. In the UK the average pension paid by the state is 134.25 Pound per week (source) in 2020. For India, a similar number is not available and even after trying to understand the Indian pension system I’m still not sure how it works exactly. If I understand it correctly the state basically only pays the pension of civil servants and a neglible amount to the most vulnurable. Everything else are systems that help people manage their personal savings but do not redistribute money from young to older generations. According to glassdoor the average salary of a civil servant in India was 832,000 rupees ($11,490) per year in 2020. This summary states that civil servants only get a maximum of 50% of their salary. Wikipedia states that there were 50,000 civil servants in 2010 which was 0.004% of the population back then. For my calculation I assumed the same ratio for 2018. Additionally I assumed that everyone receives the maximum of 500 rupees from the National Social Assistance Scheme to create an upper bound for averted payments. All numbers in my calculation account for inflation and are translated to their 2018 level to compare them to the tax revenue numbers of 2018.

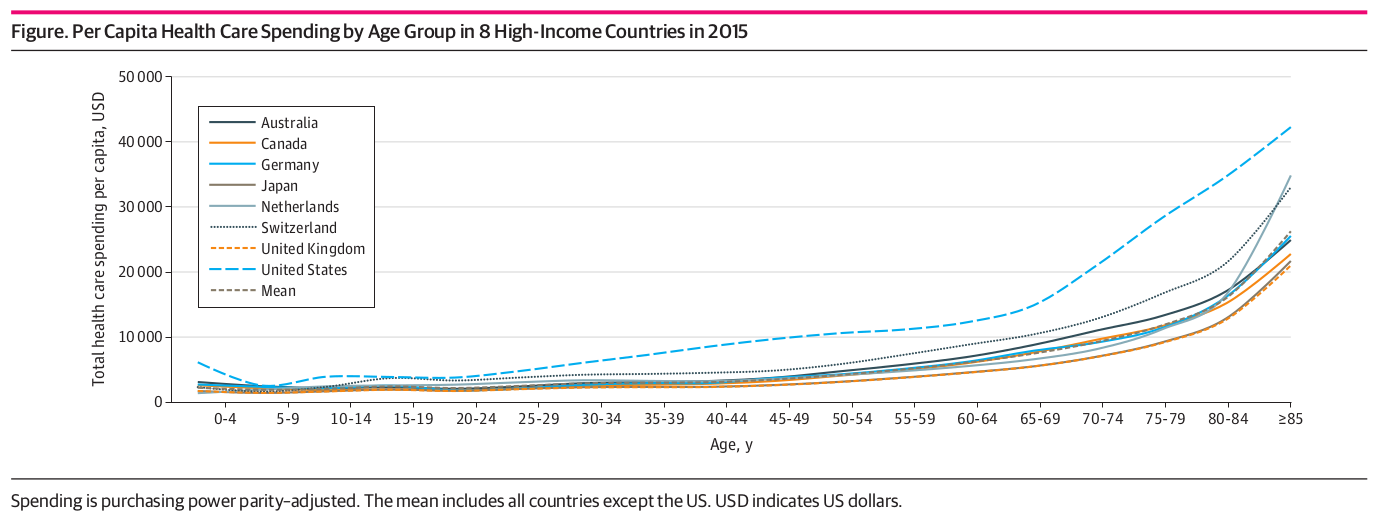

Estimating the average health care cost per person and country is also complicated because most health care schemes are pretty complex. The paper Comparison of Health Care Spending by Age in 8 High-Income Countries estimates the average spending for health care by age bracket. After converting the cost for 65+-year-olds, converting from US dollars to the respective currency, and adjusting for inflation we find that the USA on average spends $26133, Germany €10871, and the UK 7333 pounds per 65+-year-old person. For India, I couldn’t find health care spending by age bracket but public spending for health care per person in general (see statista). For most countries the health care cost for 65+-year-olds was 2.5 times the average spending so I created a similar estimate for India. This computation results in average spending of $56.9 per 65+ year old per year. While that seems pretty low compared to the other countries, I find it plausible in the context of other public spending (e.g. state pensions) in India. Similar to the Pensions, I have multiplied the pensions per person and year with the number of people who died due to smoking and the number of years lost on average due to it (i.e. 10).

Before we discuss the results, I think it is important to point out that there are a couple of assumptions in this calculation that are probably wrong (see Limitations section). Thus the following results should be interpreted with caution and seen as an overestimate of the true savings whereas the costs of smoking are an underestimate. I have thus added uncertainty estimates as detailed in the Limitations section below.

Limitations

There are many assumptions that I make here that are broad simplifications of reality and would likely change the outcome by a noticeable amount. Those include the assumption that everyone’s life is reduced by exactly 10 years due to smoking while it is a spectrum in real life, the classifications into the age-bracket of 65+ years which is also insufficiently nuanced, and many more. There are three assumptions that I find particularly important and I want to discuss further.

Most noticeably all estimates have been done at different points in time. The tax revenues all come from 2018 while the estimates on the cost of smoking are usually from earlier points in time. I only account for inflation but the underlying drivers of the cost have probably changed in much more complicated ways that I don’t account for. Hospital costs have likely increased more than inflation, at least in the West. The number of smokers has gone down in nearly all countries. We know more about the relationship between smoking and different diseases, thus current estimates would likely include a larger number of diseases. All of this leads me to believe my estimates of the cost of smoking are underestimates.

Secondly, the assumption that smokers are a representative sample of the population is probably wrong. I think there are reasons why people are more likely to smoke than others such as continuous exposure to stress or a strong desire to belong to a particular group. Since I don’t expect these and other reasons for smoking to be equally distributed in a society, I don’t expect smokers to be equally distributed either. There is some indication that the probability of smoking is inversely proportional to income (see e.g. the CDC). This would affect multiple parts of the model - pensions saved would be lower, productivity lost would be lower but intangibles such as harm through loss of family member would likely be larger. However, modeling this influence is currently impossible due to a lack of data.

Thirdly, my model assumes that by taking the average public health care costs for the 65+-year-old over ten years we can approximate the cost averted due to early smoking deaths. However, as detailed above, I don’t think this is true. People’s healthcare costs rise towards the end of their life, so if they die 10 years earlier we can just subtract 10 years of the average health care cost of 65+-year-olds. I’m actually not exactly sure how to model this fact correctly because I don’t know enough about age timelines in medicine. I would expect though that my model is overestimating the savings of healthcare spending due to earlier deaths as a consequence.

Overall my calculations are so simplistic that I would assign high uncertainty to the results. Because of the reasons detailed above, I would expect my estimates to be an overestimate of the saved costs and a more accurate estimate of the money lost due to direct costs but an underestimate of the indirect loss of productivity. Since the estimates for direct and indirect costs are done by people who have devoted more time to them I would be more confident in their estimates but still assign substantial room for over- or underestimation. As it is harder to quantify effects that are indirect and vague, I would expect the indirect cost to be an underestimate of the true cost. Because only the estimate of the indirect cost for the US reported error bars, I added my own estimates to all others. The error estimates are my best guesses after reading the sources and combining them with the arguments for over and underestimates above. My error bar for the pensions saved in India for example reflects that this is an overestimate since I pretend that more people get the maximum pensions than actually do. But I still have to emphasize that the error bars are not grounded in any specific mathematical model of uncertainty quantification but rather just my own best guesses.

Discussion of current Results

Given the limitations above, I think that the true cost of smoking would outweigh or draw even with the income from taxes combined with the averted costs in the countries in which this is not currently the case (e.g. UK). For developing and industrial nations such as India or countries with pyramidal demographics smoking seems to be a pretty big harm since the people who die are still of working age. For the USA it also looks as if smoking is clearly negative. I don’t know entirely where the difference between the USA and European states comes from but expensive health care, higher productivity or a more pyramidal demographic all seem like hypotheses worth exploring.

For me personally, the biggest update in beliefs is that old people are much more expensive for a state than I expected. Once I realized that the case for smoking is just a case for less old people I was convinced that smoking is a pretty bad way to achieve that goal. Encouraging people to have more children through various means or supporting more migration would be one way to address this demographic shift and restructuring your health care system in a UK-style fashion and apply more cost-effectiveness calculations could be another.

3. Other considerations

While the purpose of my post was to primarily answer the two questions above, I stumbled over some other interesting considerations along the way.

Jobs

There are some people who claim that the jobs within the tobacco industry, e.g. in production, advertisement, and distribution, should not be forgotten in my calculations. I personally don’t like this argument for two reasons. Firstly, I think that people usually find other jobs if their company goes bankrupt, and especially in an environment like the tobacco industry there are few jobs that require a very unique skill set that wouldn’t be applicable to other jobs. Secondly, and more importantly, I don’t think jobs should be an argument for an industry that is net negative to society. If there was an industry whose workers would run around murdering people, nobody would argue that the industry should exist because of the jobs it provides. Cigarettes aren’t as direct - the death is much later and the link is more probabilistic and thus less salient - but the underlying argument still holds true in my opinion. Especially when the people who are affected aren’t always the ones who chose to smoke in the first place. This is what I will discuss further in the next two sections.

Indirect Harms - passive smoking

One of the things that surprised me while researching for the article was how large the effects of secondhand exposure are. Remember that the indirect cost of smoking in the US was estimated to be $156 billion? Apparently $5.6 billion, i.e. 3.5% of that come from secondhand smoke exposure. In Hong Kong in 2006, the combined direct and indirect costs of smoking were estimated at $532 million for active smoking and $156 million for passive smoking, i.e. 23% of the total costs. Furthermore there are lots of studies (see e.g. [1], [2], [3]) that provide evidence for the harms of passive smoking and quantify them. They all find that being exposed to smoke from cigarettes over longer periods of time increases your risk of illness. The people who are most often victims of passive smoking are children, people living in public homes, family members such as an elderly relative, and people working in pubs and bars.

The report by the Surgeon General referenced earlier in the post also presents a picture of illnesses related to passive smoking. Once again, causality has only been established for those in red but in the context of smoking, I personally am already convinced by strong correlations. As far as I understand it they have set themselves a pretty high standard for causality, i.e. only if the physiological mechanism from inhaling the smoke to the onset of the illness is fully understood.

I guess we can all agree that nobody would want to inflict any of these illnesses to the people in our surroundings.

Moral Considerations

In my opinion, there are three moral considerations against smoking but none for it.

Firstly, as far as I can tell people don’t truly want to smoke. The reasons why they start might be a desire to belong to a group or relief stress but these are in no way necessarily tied to cigarettes. Once they started smoking the nicotine addiction then kicks in and it becomes really hard to give up. Most people I have talked to said that they would like to quit smoking or preferred not to have started it but really struggle to actually get rid of their habit. I think how bad the value-proposition of cigarettes really becomes clear in a thought experiment. Assume you could take a pill that would (with high probability) get you addicted, cost you a lot of money over your entire life, reduce your life expectancy by 10 years on average, increase the probability of having a large array of illnesses such as various heart and lung diseases AND reliefs stress and gives you a sense of belonging. I can’t think that anyone would truly want to take this pill but due to the fact that the benefits are instantaneous and the harms are all passive and long-term it is hard for people to realize the trade-off they are making. Thus I think states should ensure that the true preferences of people are fulfilled and nudge people pretty hard to prevent them from smoking.

Secondly, smoking hurts third parties, e.g. children or elderly family members. While I have quantified the effects of second-hand exposure to cigarettes above, I want to outline the moral argument here. If somebody is well-informed about all the health outcomes of smoking and still consents to do it, I could see why a state would allow that. We don’t prevent people from climbing mountains like the K2 from which one out of every five climbers dies during the expedition. But if you look at the damage done to third parties who are often dependent on the smoker and can’t opt out of that relationship because they are children or an old relative, I find that argument rather unconvincing. Thus I would heavily prioritize the innocent third party victim rather than the free choice of the smoker.

Lastly, the money spent for treating smoking-related diseases could be spent to treat people who aren’t responsible for their diseases. From the figures, we see that smoking-related diseases create direct costs and these are very likely connected to hospital space and medication paid for by the state. But, as we can also see in the figures, they also die much earlier and thus free up hospital space for others. Comparing the direct health care cost with the saved cost we find that typically the direct costs are higher than the saved health care spending but the gap is not as large as I expected. Given that direct costs are usually an underestimate and the costs saved an overestimate I still believe that the “smoker take up medical space” argument is valid but less strong.

Which Legislation works?

The rest of the article might sound like I would be in favor of banning cigarettes entirely. But that’s not necessarily the case. I support all measures that reduce the number of cigarettes smoked in an effective manner and making them illegal might not be the most effective route to achieve that since people might switch to the black market which doesn’t provide tax income.

Broadly speaking there have been three kinds of state interventions to reduce tobacco consumption. They are a) mass reach communication campaigns, e.g. informing the population about the health risks or showing emotional stories of smokers, b) increasing the price of tobacco products through taxation, and c) comprehensive free smoking policies, e.g. banning smoking in public buildings or restaurants. All of them showed a measurable reduction in smoking. According to the CDC the communication campaigns show a median decrease of 5.0 percentage points in the prevalence of tobacco use among adults and a median relative increase of 132 percent in the number of calls to quitlines. They are estimated to have a benefit-to-cost-ratio ranging from 7:1 to 74:1. Increasing the price of tobacco results in a 7.4 percent reduction in demand among adults ages 30 and older and a 14.8 percent reduction in demand among young people ages 13-29. The free smoking policies resulted in a decreased exposure to secondhand smoke (50 percent reduction in biomarkers). There are even more results of these interventions which you can find on the CDC website and their source materials. Most of these results seem like very effective and cost-efficient government interventions and we have seen governments around the world slowly adopting them.

The tobacco industry always argues against increases in tobacco taxation because that would increase the share of cigarettes on the black market and thus decrease state revenue. To some extent, this has also been shown in multiple studies. The paper “Cigarette Taxes and Illicit Trade in Europe” claims that “a one-euro increase in tax per pack in a country is expected to increase illicit market share by 5 to 12 percentage points and increase illicit cigarette sales by 25% to 120% of the average consumption”. But there is also evidence that the tobacco industry is systematically overstating the impact of tax increases on illicit trade (see e.g. here).

My personal opinion after reading parts of the literature is that states should slowly but surely increase the tax on tobacco to a significantly higher level. This means that some people will quit and some will switch to cheaper black market alternatives. Since the majority of gains from cigarettes for a state don’t come from taxes but rather from premature deaths and the averted pensions and health care costs the group that quits is much more valuable than the tax revenue lost. A 2020 report of the Surgeon General on Smoking Cessation also showed that quitting smoking is always related to improved health outcomes, i.e. it is never too late to quit smoking.

Conclusions

If you are a smoker and feel attacked by this article, I’m sorry. While I can understand how people started smoking, I don’t think there is a good justification for it. There are better ways for stress alleviation with less risk and there are better ways to belong to a peer group. If you already agree that smoking is bad for you, there are ways to stop and you can get help. Remember that it’s never too late to try to stop smoking and your future self will only thank you for it.

In order of perceived importance my conclusions are:

- To a large extent calculating the cost and the revenue of smoking-related illness is just an exercise in creative accounting. Especially when the people who estimate the numbers are ideologically motivated, e.g. a libertarian think tank arguing for smoking or anti-tobacco groups arguing against it the numbers tend to be either pretty clearly for or against it. Even in the cases where non-ideological actors such as scientists make an honest effort to estimate the true number it is still very hard. For example, some diseases appear more often in people who smoke but might just be a result of their socio-economic background and thus not causally related to smoking. Disentangling these and many more factors is quite hard, if not even impossible given the current data. Thus I have very high uncertainty in my estimates.

- Putting the complexity aside my best estimate is that smoking is a net negative for the state in the vast majority of cases.

- My methodology underestimates costs and overestimates gains from smoking. Since the scientists are usually concerned with rigor they often only include those diseases that are very certainly related to smoking, thus undercounting the true cost. Furthermore, there might be relationships that we don’t understand yet underestimating the true costs even further. The gains from premature deaths on the other hand are likely an overestimate since I used average estimates for pensions even though smokers tend to be disproportionally from lower-income backgrounds. Thus the figures presented might be slightly deceptive if you ignore the error bars.

- The income from smoking does mostly not come from tax revenue but rather from the pensions and health care saved from premature deaths. Essentially, the entire reason for why this argument might have a chance at all is because old people are expensive for a state and cigarettes tend to kill them earlier. Thus I conclude that for countries with pyramidal demographics, e.g. many developing countries the cost of smoking is much larger than the potential gains. For countries with less pyramidal demographics, I would estimate that smoking is on average still a net negative. However, there might be specific circumstances that make it possible that the cost averted outweighs the harm inflicted on a financial level. This calculation does not include the emotional harm of lost family members or other loved ones though.

- I would still heavily advise people and states against smoking. On a personal level, trading some instant stress relief for 10 years of your life and a significantly increased risk for many really nasty diseases seems like a bad value proposition especially because the advantages of nicotine can also be accessed without the harms of smoking, e.g through nicotine gum. On a societal level, there are many people who are harmed through passive smoking while never having the chance to opt out of that relationship because they are vulnerable, e.g. children or elderly family members. I think those who are innocent and don’t consent to this lifestyle should be prioritized over your personal right to self-harm. I am aware that it is very hard to quit and it is an uphill battle but there are many organisations and people who can help and make this journey easier.

One last note

If you want to get informed about new posts you can subscribe to my mailing list or follow me on Twitter.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.