What is this post about?

I recently wrote a blog post on “the case for GMOs”. During my research, I stumbled on the Wikipedia page on golden rice. I had heard of golden rice before but I hadn’t looked at it in detail. Basically, it is a genetically modified version of rice that leads to a higher production of Vitamin A. I was really surprised because the scientific evidence is insanely one-sided — golden rice creates no harm, just saves a lot of lives. And yet it is banned in the vast majority of countries.

In this post, I want to very roughly evaluate whether golden rice should be of interest to EAs and whether genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in general are worth investigating deeper. My evaluations are mostly concerned with Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) and golden rice — only the last section explicitly focuses on GMOs in general.

Epistemic status: This really is a very rough sketch. I spent about 15 hours on this post. I’m not an expert in GMOs nor in influencing governments. There is a chance some of my claims are wrong. I try to quantify my uncertainty wherever possible.

I have previously posted this article on the EA forum.

Executive summary

All of the following are my own estimates, people interested in working on the topic should do further research.

- I think there is some unused space in the overlap of EA and GMOs and specifically golden rice. However, I think it’s implausible that it is nearly as effective as the GiveWell top charities. This mainly comes from the fact that supplements and other alternatives seem to have already solved the problem to the largest extent.

- Scope: about 25,000 people die of VAD annually. This is much smaller than e.g. the 500,000 thousand people dying of Malaria per year.

- Tractability is high and comparable to AMF’s bednets for some interventions, e.g. we can run random control trials (RCTs) by giving some villages golden rice but not others. There are also less tractable interventions such as influencing governments’ stance on GMOs.

- Solving VAD through golden rice seems harder than solving Malaria through bednets because you not only have to think about logistics and funds but also have to sway the public’s and lawmakers’ opinion on GMOs. My rough guess is that even in the best case, working on golden rice would still be 2x less efficient than the AMF (see conclusion; intuitive estimate, no quantitative model).

- While golden rice might not match AMF levels of efficiency, there could probably still be some EA-aligned organizations working on using GMOs to fight malnutrition. The upside of saving lives with such simple products is just too large for EAs to entirely ignore. These organizations could work on

- Cooperating with local organizations to lobby developing countries’ governments.

- Cooperating with local environmentalist groups and farmer alliances to reduce their opposition to GMOs.

- Working on distribution in countries that legalized golden rice, e.g. the Philippines and soon Bangladesh.

- Reducing the legal burdens of GMOs around the world to increase innovation more broadly.

- Working on new GMOs to solve different kinds of malnutrition.

- If you want to dig further into this, I would recommend contacting the golden rice project. Also, some EA organizations such as the good food institute, Open Phil, rethink priorities, charity entrepreneurship and others might have thoughts, recommendations, or funding.

What is golden rice?

Vitamin A deficiency (VAD)

VAD is most common in poorer countries and affects around 1 billion people annually. The Wikipedia page on VAD states that “VAD claims the lives of 670,000 children under five annually”. The claim seems to come from a 2008 study. The Wikipedia page on Golden Rice claims that “up to 2.7 million children could be saved from dying unnecessarily”. It is not clear to me whether this is annually or cumulatively. Furthermore, the reference for this claim is goldenrice.org which cites only studies conducted before 2005.

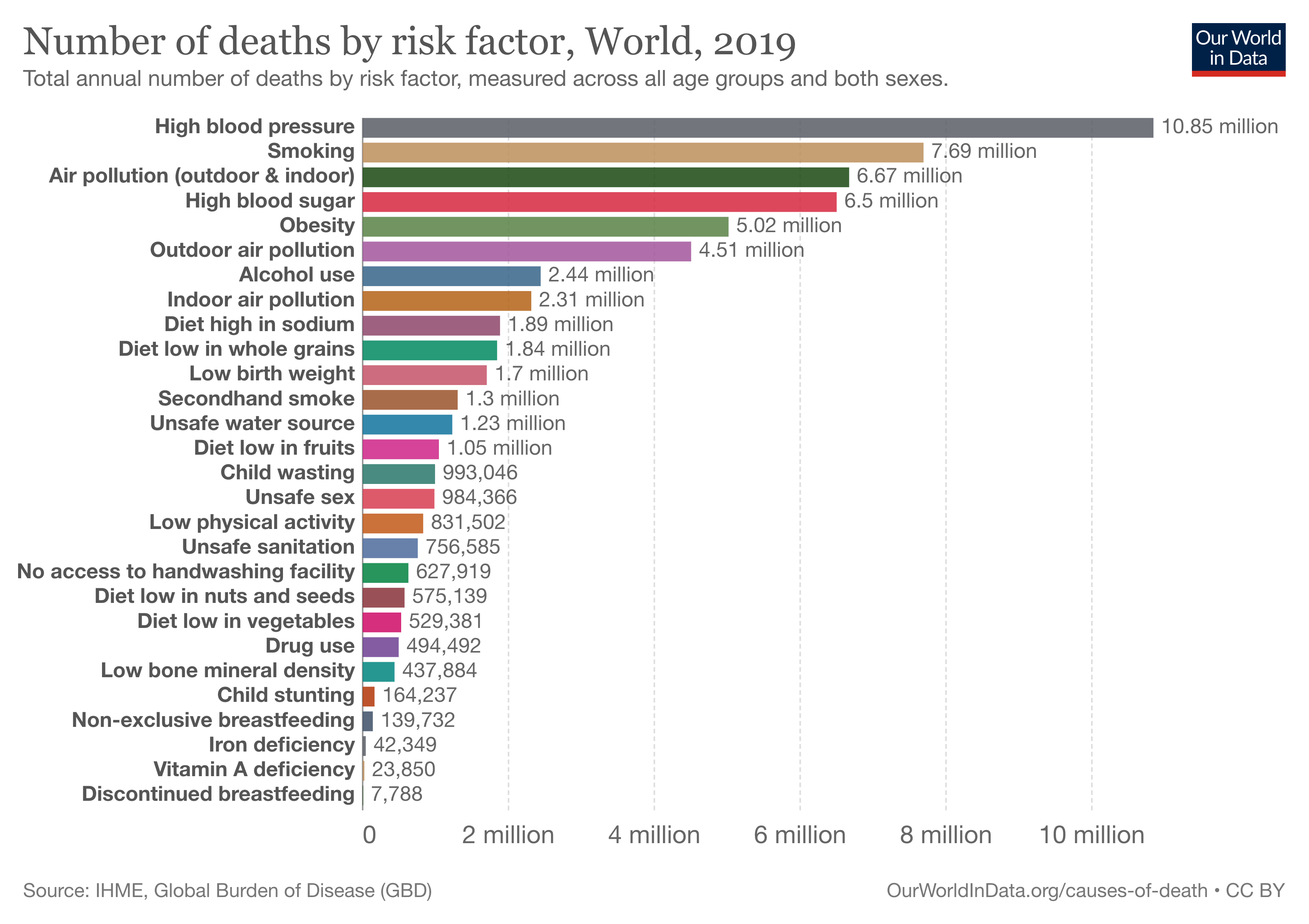

2019 numbers estimate the death toll of VAD to be 23,850. From this, we can conclude that the measures of the last 20 years have been pretty successful in reducing fatalities and the Wikipedia pages are uninformative and out of date.

However, VAD is still not entirely solved. A 2021 UN report claims that “only 41 percent of targeted children [in selected developing countries] were reached [by vitamin A supplements] in 2020, with West and Central Africa achieving the lowest coverage at 29 percent”. Furthermore, a 2021 study estimates that “The overall prevalence of VAD [among children] in India is 17.54%”.

So it looks like VAD is not very deadly but still a real problem for a lot of people and particularly children.

Other, more common, negative outcomes of VAD include blindness due to a lack of Rhodopsin which is necessary for adaptation to dim light and an increased risk of other infections (e.g. measles and eye diseases) because vitamin A plays a role in T cell replication.

How does golden rice work?

Golden rice is “genetically engineered to biosynthesize beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A, in the edible parts of rice.” There is empirical research that confirms that golden rice indeed decreases VAD and is safe to consume.

Backing of the scientific community

The vast majority of the scientific community is in favor of GMOs and specifically golden rice (see opinion polls below). There is a letter by 158 Nobel laureates that urges green parties and environmental organizations to reconsider their opposition to GMOs because study after study indicates that the benefits outweigh the harms.

Furthermore, there is a Wikipedia page on Genetically modified Food Controversies that says “food derived from GM crops poses no greater risk to human health than conventional food” and “members of the public are much less likely than scientists to perceive GM foods as safe”. Both of these claims are supported by multiple studies.

Alternative solutions to VAD

While golden rice is banned in most countries, politicians, NGOs and other players have tried to solve VAD with other strategies.

There are global initiatives such as the Global Alliance for Vitamin A which is an informal partnership between Nutrition International, Helen Keller International, UNICEF, WHO, and CDC. Their strategies include the provision and distribution of Vitamin A supplements, nutritional education of parents, and more.

They claim that “An estimated 1.25 million deaths due to vitamin A deficiency have been averted in 40 countries since 1998” and a 2017 meta study concluded that Vitamin A supplements reduce overall child mortality by 12%.

The same report also mentions that Vitamin A could be distributed through food, e.g. golden rice or Vitamin A-enriched sweet potatoes. This would reduce logistical overhead drastically.

However, supplements are by no means sufficient to solve VAD for everyone (at least for now). Our World in Data, for example, provides a year-by-year visual for the coverage of Vitamin A supplements. While there are some improvements, there are still countries that have less than 20% coverage today.

Progress on golden rice

The original scientists behind golden rice founded the golden rice project, an NGO that educates the public and works towards the legalization of golden rice and GMOs in general. In 2021 they published a piece called “Allow golden rice to save lives” in which they detail the case for golden rice and the hurdles they are facing.

In 2021, the Philippines became the first country to fully legalize the cultivation and distribution of golden rice. Other countries such as Bangladesh, may soon follow.

There are also organizations such as iGEM or the Alliance for Science that actively engage in scientific education and projects around GMOs.

Misinformation

While there are some negative aspects to GMOs, most of the public opposition is overblown or entirely made up (see section on NGOs against GMOs). Many people still think that GMOs lead to negative health consequences even though the scientific consensus is that this is untrue. Many people fear that there are mutations that could destabilize biospheres even though the evidence for that is very weak.

While this is a sad state of affairs, organizations promoting GMOs should still be aware of it because they will have to argue against this sentiment.

What are the bottlenecks?

Politics

The fact that most GMOs are illegal and the approval process is very complicated and lengthy implies that politicians have had some reasons not to like GMOs. I think there are many plausible explanations for this.

A lack of knowledge/education might play a role, but I don’t think GMOs are more complicated to understand than, let’s say, supply chains. So I don’t think it’s the main driver.

In general, I would assume that politicians’ opinion on most things is a function of public pressure, interest groups, etc. Therefore, if you change the underlying drivers they will change their mind and actions.

Unfortunately, the system is rigged since dead/future children don’t vote. The people who are most affected by the lack of GMOs/golden rice, i.e. children who die from it or future children are not able to voice their opinion. In contrast, their opposition can and does use its influence.

NGOs opposing GMOs

Pressure groups against GMOs include environmental NGOs like Greenpeace and representative groups of local farmers that fear GMOs for various reasons.

Environmental NGOs like Greenpeace say that “Genetically modified (GM) crops encourage corporate control of the food chain (1) and pesticide-heavy industrial farming (2). GM plants can also contaminate other crops and lead to ‘super weeds’ (3). This technology must be strictly controlled to protect our environment, farmers and independent science.”

The scientific consensus is that there is little to no evidence for (3) if only because most GMOs can’t reproduce. While some GMOs are pesticide-resistant, it is unlikely that (2) is true just because GMOs can be engineered to have resistances such that fewer pesticides are needed for the same amount of yield.

It is true that farmers depend more on seed producers like Monsanto when they use GMOs and I think it is one of the main bottlenecks for widespread adoption. However, farmers could still choose to use their own non-GMO seeds if they wanted to or change seed providers if they are unhappy with Monsanto. It feels like this is less of an inherent GMO problem and more of a problem of economic environments.

Organizations that represent local farmers such as slowfood.com argue that GMOs reduce the power of local farmers in favor of big international companies. They cite that local farmers are sued by Monsanto & Co because GMOs from neighboring fields pollinated their crops and thus breached IP laws. Furthermore, they argue that by giving control to the big companies, local farmers are not allowed to experiment with their own seeds and thus valuable improvements and adoptions are lost.

I think these are real problems but they are not inherent to GMOs. Rather, they come from unbalanced regulatory frameworks or market failures. However, it is necessary to address them since the farmers play a key role in the adoption of GMOs.

Public opinion

Public opinion on GMOs is very different from the scientific consensus.

A 2020 poll conducted by the Pew Researcher Center in 20 countries concludes that 48% of people think GMOs are unsafe vs. 13% who think they are safe (median estimate). There is some variance between countries, e.g. in Russia, 70% think it’s unsafe vs. 9% safe, whereas in the Netherlands it’s 29% unsafe vs. 20% safe. The remaining respondents indicated that they don’t know enough to give an answer.

A 2015 poll among scientists and the general public, also conducted by the Pew Research Center concluded that 37% of the US public and 88% of US AAAS scientists think that GMOs are safe.

Distribution

Once GMOs are legal, they still need to get to those who need them, e.g. those with VAD. Ultimately, I think markets will solve that and distribution will be done by for-profit actors. However, this process can likely be accelerated significantly, by actively working on supply chains, logistics and information campaigns.

I think the initial distribution and education campaign could look very similar to what the AMF is currently doing.

Other use cases of GMOs

Malnutrition is still a big problem. According to a report by the WHO, UNICEF and the World Bank, there were 45.4 million children whose life is threatened by wasting (too thin) and 149.2 million children whose life is threatened by stunting (too short) in 2020.

Furthermore, the UN estimates that about ⅓ of all women of reproductive age are anemic, i.e. the hemoglobin concentration in their blood is too low. The most common causes of anemia include nutritional deficiencies, particularly iron deficiency, though deficiencies in folate, vitamins B12 and A are also important causes.

Other micronutrient deficiencies include zinc and iodine. For further information, you should check out this Our World in Data article.

I’m not an expert in GMOs but my naive model is that you could engineer some foods to contain some of the relevant micronutrients. Maybe it doesn’t work with all foods and probably it will take some time to get it right but it should be possible, right?

For example, there are already successful efforts to modify cassava to contain more iron and zinc.

The advantage of GMOs compared to supplements is that they would just be integrated into people’s daily routines and not require regular distribution and overhead. The green revolution has already saved an estimated billion lives, why not finish the job?

I expect that there is space for an EA-aligned organization/start-up to work on the production, distribution, logistics, etc. of GMOs to fight hunger-related problems.

Of course, GMOs can be used for much more than to fight malnourishment. They can be used to fortify food against climate change, increase resistance against insects, and much more (see comment by tessa). Another example would be to genetically modify Malaria mosquitos to not transmit the disease anymore (see comment by Michael Huang). I just picked malnutrition as one example to think about in more detail.

Should golden rice / GMOs be a cause area?

Scale

The death toll of Vitamin A is estimated to be 23,850. This is much smaller than e.g. Malaria, which claimed 627,000 lives in 2020. However, there are still a lot of people who have VAD without dying.

Other symptoms of VAD seem to be very painful. They include blindness or increased risk of infections.

Compared to most other global health and development interventions the scale seems to be small.

Other micronutrient deficiencies are harder to quantify. Iron and zinc deficiency, for example, seem to be more common but much less deadly than VAD. I’d appreciate help from someone with more expertise.

Neglectedness

Golden rice and GMOs have the backing of the scientific community and some organizations such as the golden rice project actively lobby and fight for their legalization. However, given the size of the problem, I feel like there is some room for new organizations, especially when they apply EA principles.

There are groups such as the Global Alliance for Vitamin A that fight Vitamin A in other ways. The supplements they distribute are cheap but require distribution and need to be taken multiple times a year which increases complexity. They themselves state that Vitamin A-enriched food might be a superior alternative because it removes this logistical overhead.

GMOs in the Western world seem less neglected to me. There is a market incentive for large companies to lobby politicians. Developing new GMOs for the developing world might be more neglected since the purchasing power, and therefore the financial incentive is much smaller. This is a hypothesis, maybe lobbying the West could be effective as well.

Tractability

The distribution of golden rice seems to be as tractable as bed nets to fight Malaria. It is easily possible to conduct RCTs between villages or regions and VAD is overall easily measurable. Furthermore, the selective legalization by some countries (e.g. the Philippines) might actually yield some natural experiments in the near future. Other interventions such as lobbying and campaigning are likely much less tractable.

The same seems to hold true for adding other micronutrients to foods. Instead of rice, you just have another food to run your RCT with. Lobbying and campaigning are similarly hard to track for other GMOs.

Further thoughts

Most GMOs are illegal by default. The EU, for example, uses a cautionary approach, i.e. every new GMO food has to go through a long process to enter the market and extensive post-release monitoring. Since there is little evidence that GMOs are more dangerous than other food, this process seems overly cautious to me and could stifle innovation in agriculture. This might be something that EAs interested in progress studies could add to their repertoire.

I think there is a very slim chance that golden rice gets legalized in most countries soonish. The Philippines just started and Bangladesh is on its way. When other countries realize the benefits they might change their stance as well in a domino-like fashion. However, while I wish it was true, I think this scenario is very unlikely. Public opinion is against GMOs and environmental groups and farmer alliances are powerful actors. So even a 5-year acceleration through EA efforts could already benefit millions of children globally.

Future directions

- Working with politicians to legalize GMOs: This might be especially important for organizations that intend to influence legislation in developing countries. If you have politicians on board, they could try to sway public opinion as well.

- Working with NGOs currently opposing GMOs: Environmental activists are strongly opposed to GMOs for various reasons. Some of these reasons are factually wrong (e.g. super-mutants) and others have less to do with GMOs than the economic environment (e.g. monopolies). Convincing them to shift their focus away from GMOs towards ensuring fair distribution or helping farmers seems very important. For inspiration and an example of what that could look like you can check out Leah Garcés’ 80K podcast on turning adversaries into allies.

- Informing the public about GMOs: The scientific evidence on GMOs is pretty clear—they work and they are safe. However, public opinion is still pretty strongly against them. Information campaigns might not only be effective but also necessary to ensure widespread adoption in developing countries.

- Distributing GMOs: Once GMOs are legal adoption could still take a while. Actively organizing the distribution similar to how the AMF organizes the distribution of bednets could be an important step in the chain. This strategy could already be applied in the Philippines and Bangladesh.

- Working with politicians on distribution: Once countries have legalized GMOs, they should be interested in making sure their citizens get their improved food. Working with them on an effective scheme could improve rollouts dramatically.

- Developing new GMOs: There are already GMOs for VAD and for iron and zinc deficiencies. However, extending the spectrum for different cultures and climates seems like a reasonable option.

Conclusion

I think there is some unused space in the overlap of EA and GMOs and specifically golden rice. However, I think it’s implausible that it is nearly as effective as the GiveWell top charities. This mainly comes from the fact that supplements and other alternatives seem to have already solved the problem to the largest extent.

However, I think it is unlikely to reach AMF levels of efficiency with golden rice. In a scenario where swaying public opinion and changing laws is very easy, the distribution and adoption seem to be comparable to AMF’s work. Since their logistical work is insanely efficient and hard to match, I would say it’s at least 2x less efficient than the AMF (rough guess). In the worst-case scenario, efforts will run against a wall, public opinion is hard to sway and politicians move very slowly. Then, it would be much less efficient.

The only upside of golden rice is that the market will take over some or even large parts of the distribution which is not the case for bednets.

While golden rice might not match AMF levels of efficiency, there could probably still be some EA-aligned organizations working on using GMOs to fight malnutrition. The upside of saving lives with such simple products is just too large for EAs to entirely ignore. These organizations could work on

- Cooperating with local organizations to lobby developing countries’ governments.

- Cooperating with local environmentalist groups and farmer alliances to reduce their opposition to GMOs.

- Working on distribution in countries that legalized golden rice, e.g. the Philippines and soon Bangladesh.

- Reducing the legal burdens of GMOs around the world to increase innovation.

- Working on new GMOs to solve different kinds of malnutrition.

One last note

If you want to get informed about new posts you can follow me on Twitter.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.