This article was written by Samuel Scheuer and Marius Hobbhahn (equal contribution).

Nuclear power is a very polarized issue. Proponents think it is a clean solution to most of our energy problems and opponents think it is too dangerous or too expensive. In this post, we want to take a deeper look at the case for and against nuclear while trying to be as unbiased as possible.

Executive summary:

Disclaimer: Samuel does an MSc in Environmental Change and Management at Oxford but has no special focus on nuclear energy. Marius has no expertise in nuclear energy and just likes to dig deep into topics. There is a chance we might have misunderstood important details. You should think of the following as our best guess after spending a collective ~50 hours on it. Both of us were proponents of nuclear before doing this research but we are now considerably less convinced of its value.

Answering questions about nuclear power is more complicated than we assumed. However, there are a couple of things we can say with high confidence.

- Nuclear power is a carbon-neutral, stable source of energy that gives you high independence from other countries and conflicts.

- Nuclear power is likely very safe and creates way less harm than e.g. a coal power plant of similar size.

- The nuclear waste problem is likely neither very big nor very expensive.

- On average nuclear energy is more expensive than renewables (~2x) and we can expect this gap to widen in the future.

On the other hand, there are a couple of other questions that carry more uncertainty.

- Some people argue that nuclear energy regulation is unreasonably stringent and thus prevents innovation and inflates prices. The majority of reports (pro- and anti- nuclear) don’t mention overregulation as a major problem. We think the narrative is plausible because of misaligned regulatory incentive structures but we aren’t very confident.

- The “true cost” of nuclear energy is hard to determine because it depends on specific timelines (e.g. waste management) and discount factors. Therefore, all arguments around “nuclear is cheap/expensive” carry considerable uncertainty. Our best guess is that nuclear is and will stay on the more expensive side of energy production.

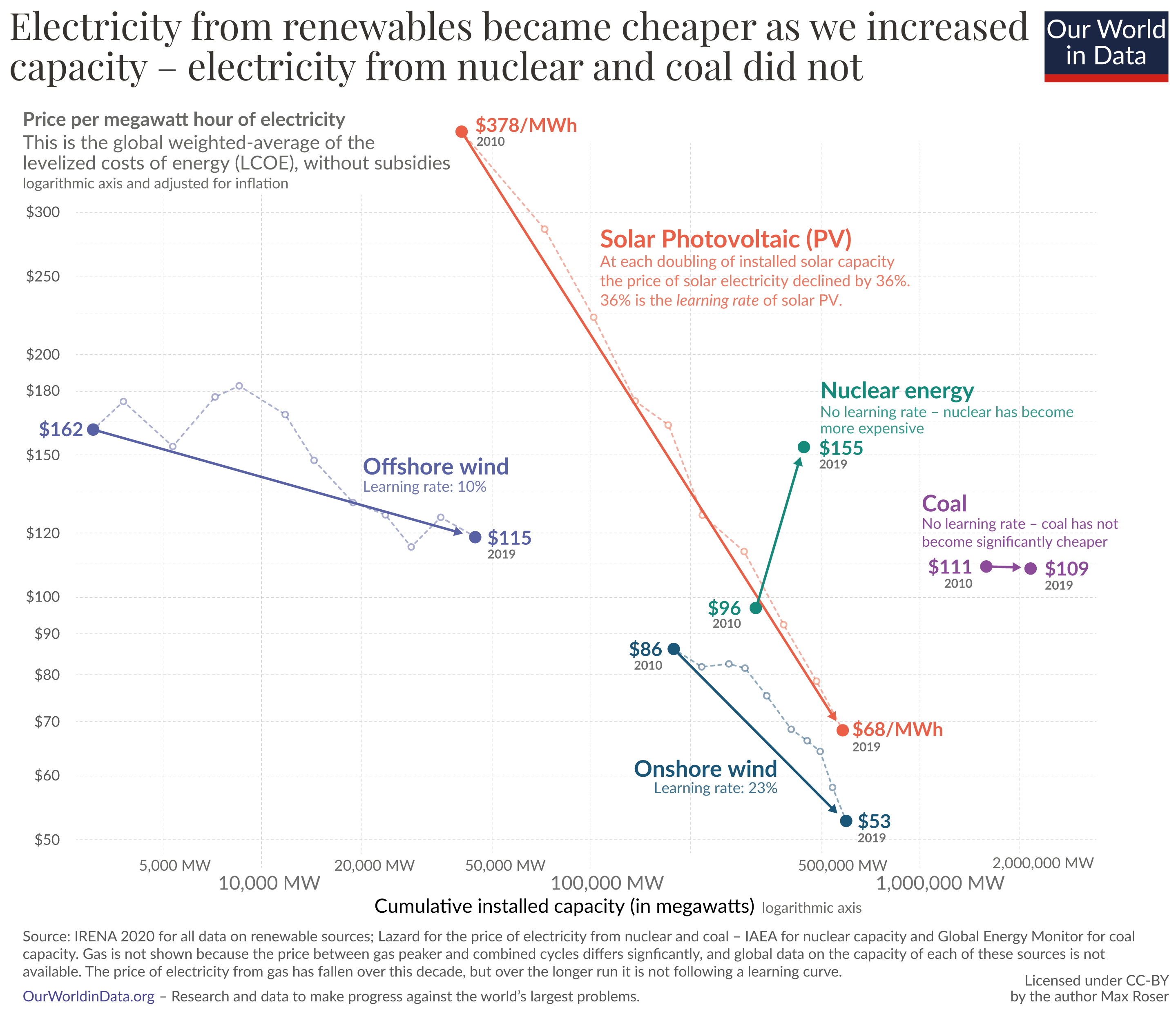

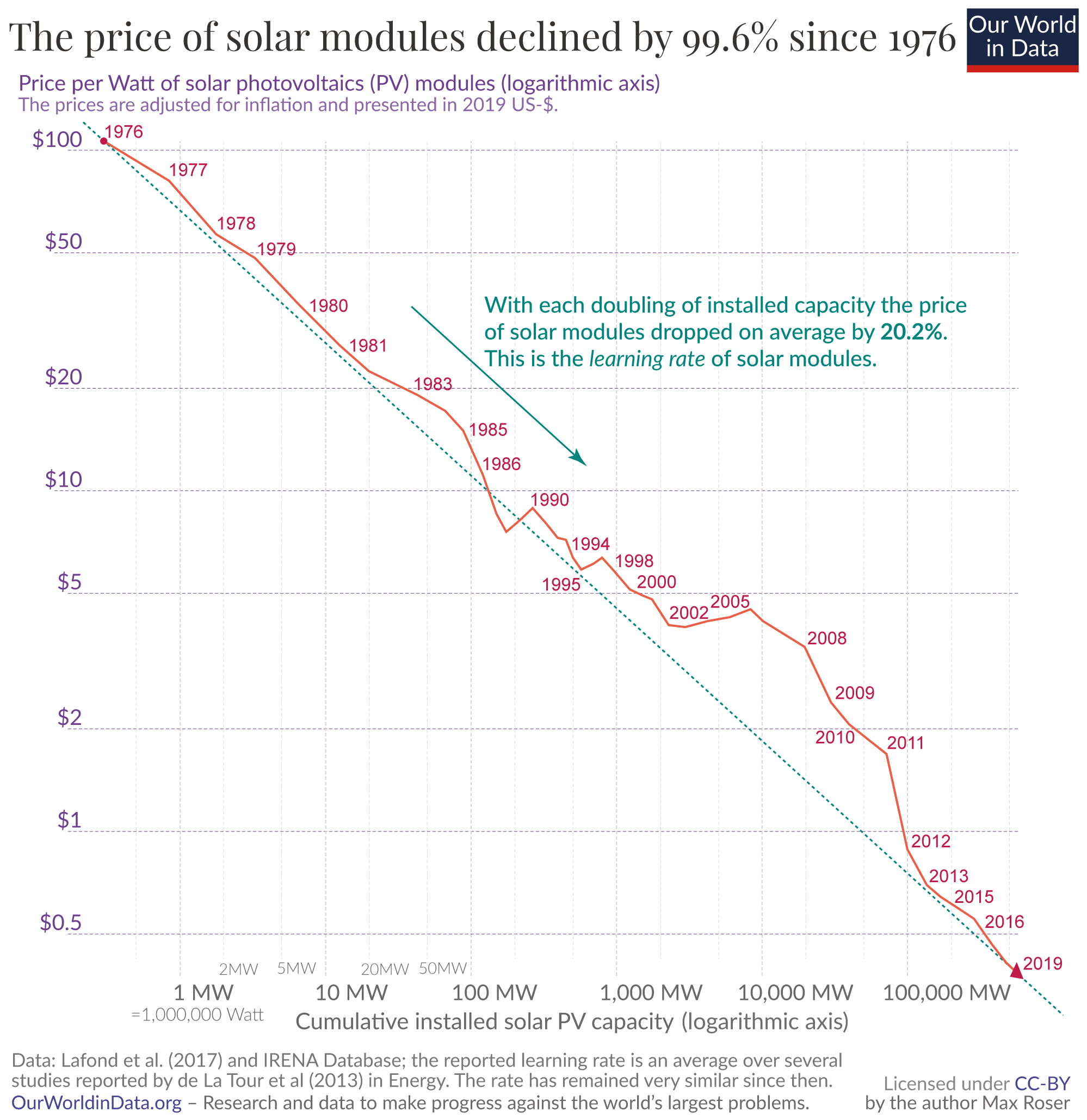

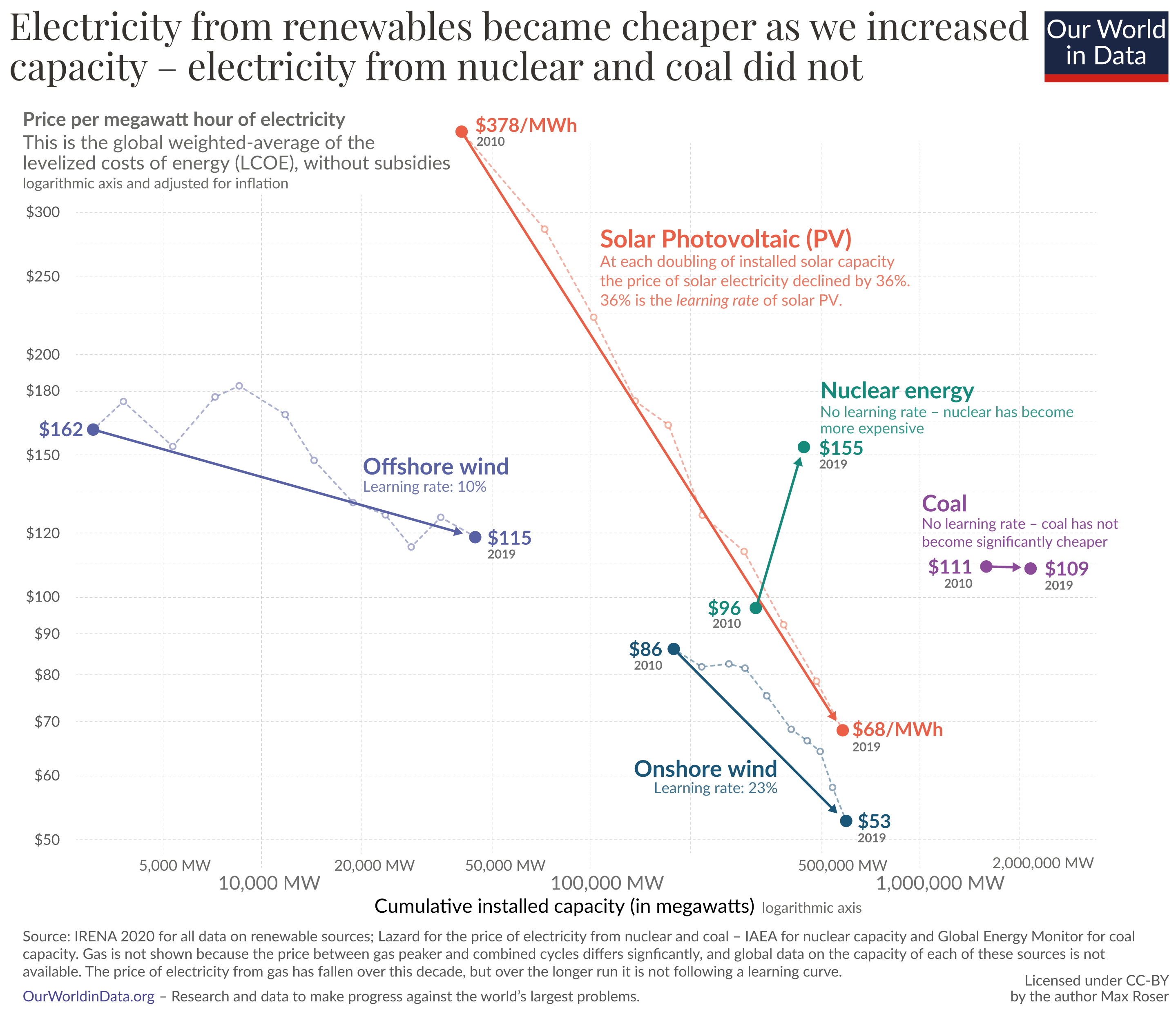

- There are many people who claim that “nuclear just needs more innovation/research”. However, governments have invested large amounts of money into nuclear energy research over the last 70 years and progress has remained slow and produced underwhelming results. There is a chance we just haven’t found the breakthrough yet but we think that is unlikely—especially when the alternative is renewable energy which has shown insane speeds of progress (see below). We speculate that this stems from systemic factors, e.g. because nuclear doesn’t profit from economies of scale as much as renewables do.

- The role of nuclear in a world dominated by renewables is unclear. Nuclear takes long to ramp up and is only profitable with high uptime. Therefore, it is not very compatible with the high volatility of renewables—at least in its current form.

- Framing: In general, we find it useful to think of nuclear energy has a high-risk, high-reward investment. There is a small chance we can get the price down significantly and then nuclear will be god-tier and there is a large chance it will always be too expensive.

Practical implications:

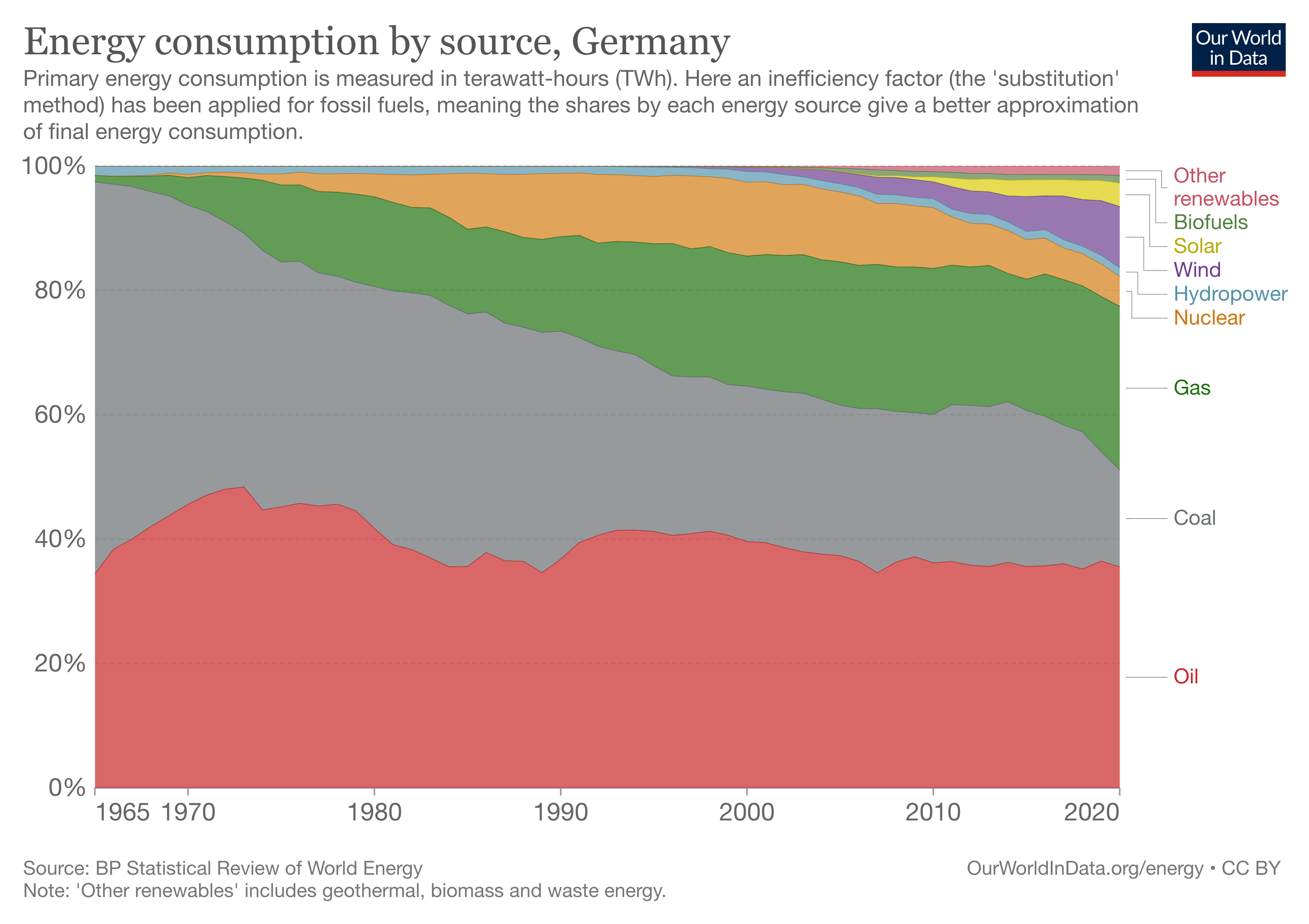

- It does NOT make any sense to close existing nuclear power plants unless you can guarantee that their energy will be replaced by 100% renewables and storage+distribution has been sorted out.

- Nuclear is nearly always better than fossil fuels. It creates way fewer health problems and GHG emissions. However, it needs more time to ramp up a nuclear reactor than to turn a gas burner on and off. Therefore, nuclear is mostly useful for baseload energy production and not to offset fluctuations in renewables.

- We think there are two possible pathways forward

- Do nuclear but the right way: reform nuclear regulations to allow for more innovation, build explicit testing hubs where it is possible to do research into new reactor designs with relative ease, build smaller reactors that follow a standard design to use economies of scale, and do more research on how to integrate nuclear into a grid dominated by renewables.

- Double down on renewables and storage: The price of solar power and batteries has dropped exponentially while their installed capacity has increased exponentially (see figure below). Doubling down would mean investing in large stationary batteries or hydrogen for storage, investing in better electrical grids to balance the consumption-production-asymmetries, and so forth.

These two paths are, of course, not entirely mutually exclusive, but if we had to design a budget right now, we would put much more resources towards renewables and storage than nuclear after doing this research.

The basic case for nuclear

Before we get into the nitty-gritty details, let’s revisit the basic case for nuclear.

First of all, it’s clean energy. During deployment, nuclear power plants produce no greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The implicit GHG emissions from building the plant or the preparation of uranium are relatively small.

Secondly, nuclear power is a stable baseload, i.e. it is independent of wind, sun and other circumstances. It takes about 12 hours to ramp up a nuclear power plant and it requires high uptime to be economically feasible. This might make it unfit to counterbalance the rapidly changing energy production of renewables (details in later section).

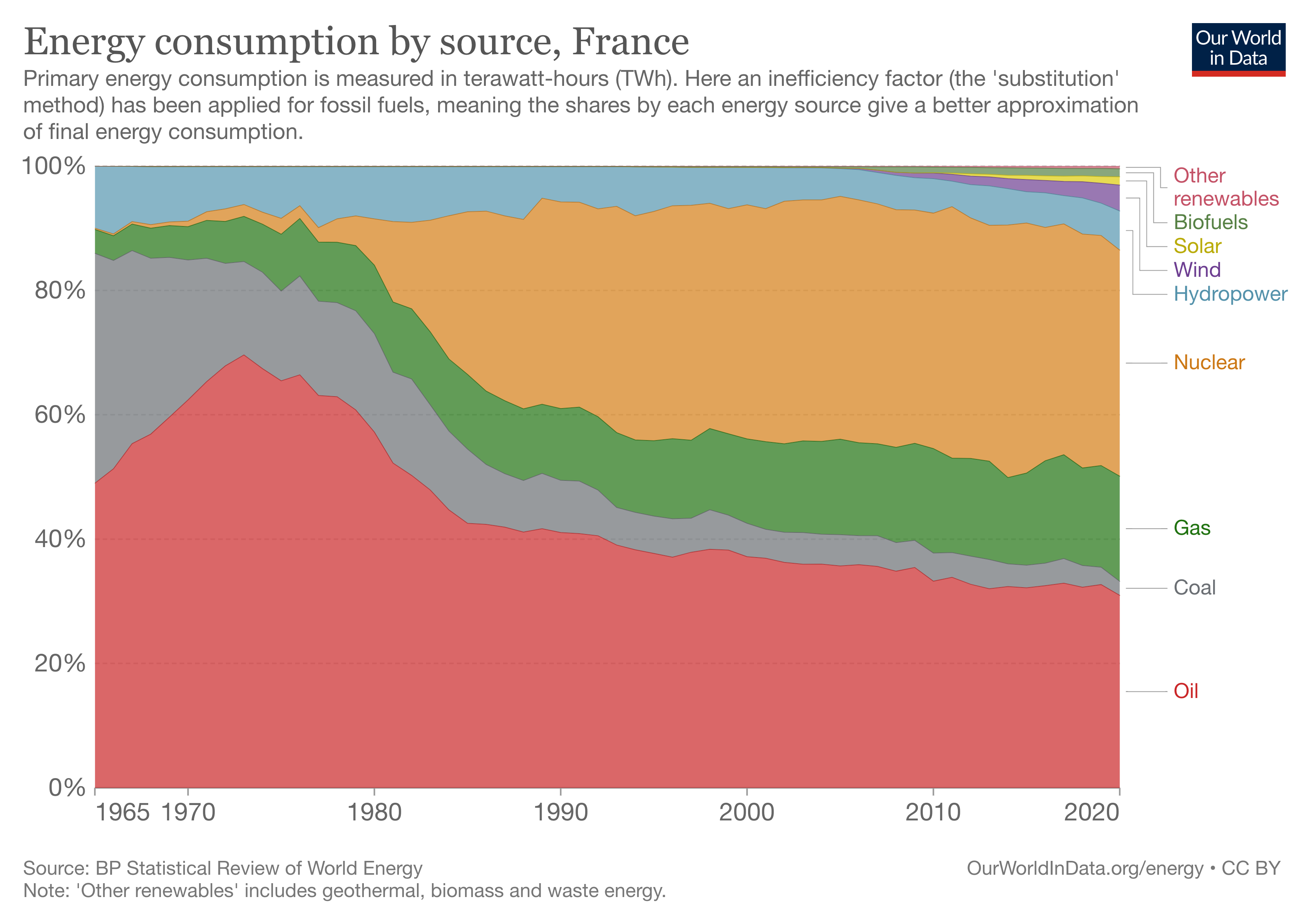

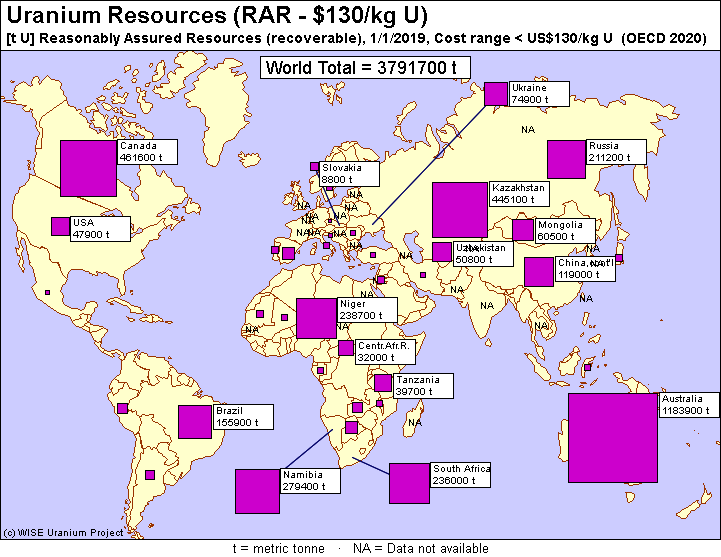

Thirdly, nuclear power gives you energy independence. This became very clear during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. France, for example, had much fewer problems cutting ties with Russia than e.g. Germany. While countries might still have to import Uranium, the global supplies are distributed more evenly than with fossil fuels, thereby decreasing geopolitical relevance. Uranium can be found nearly everywhere.

How safe is nuclear?

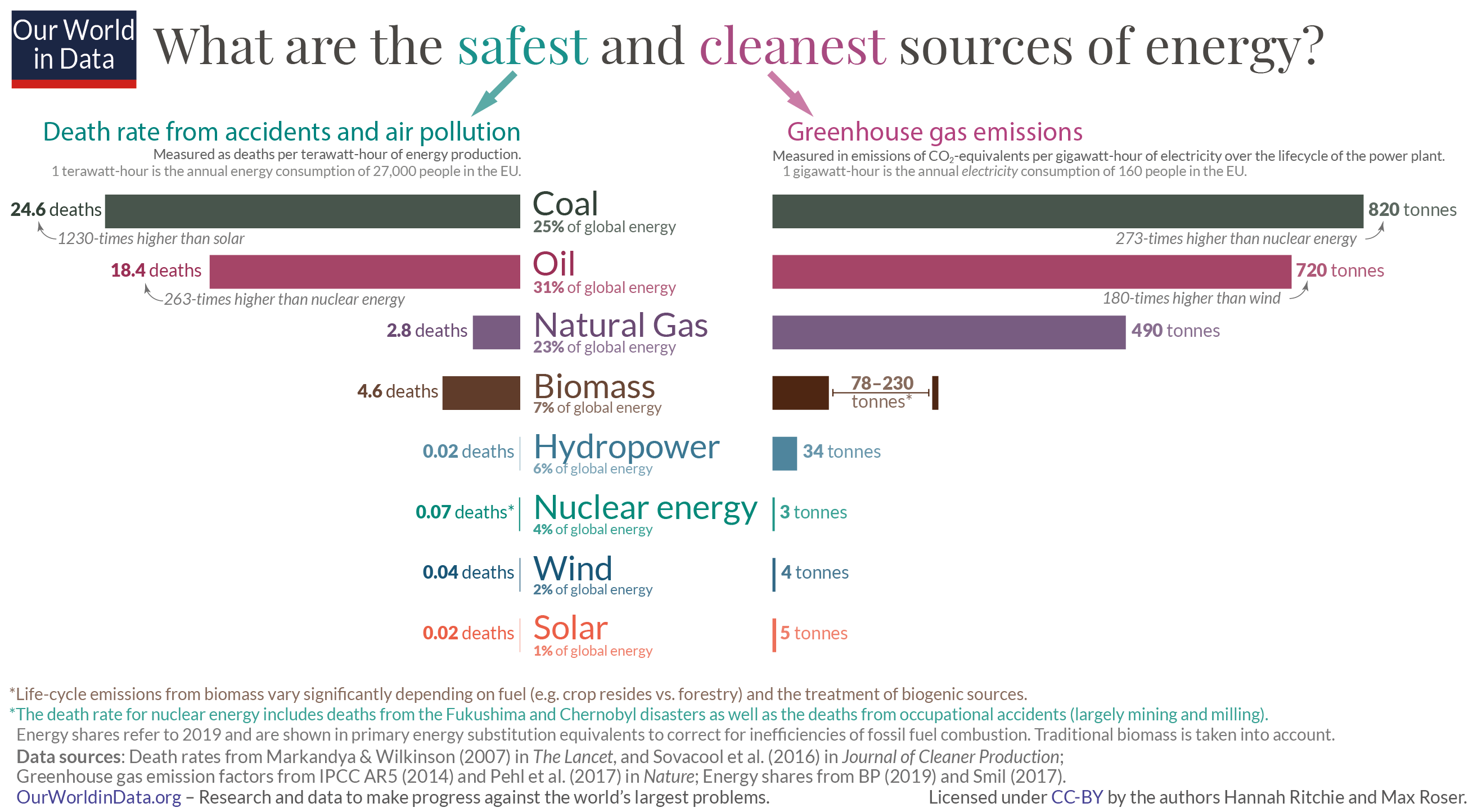

One of the most common concerns with nuclear energy is safety. People often cite the incidents in Chernobyl and Fukushima as prime examples. However, in Chernobyl (which was the worst incident so far) only 28 people died directly and up to 4000 further deaths are linked to the disaster. In Fukushima, only 3 people died. If you sum up all casualties even including mining and milling, the death toll of nuclear is 1230 times lower than for coal and 263 times lower than for oil (see Our World in Data for more).

The large death toll of coal and oil comes from air pollution which is much more deadly than conventionally assumed. In 2019 alone, 95000 infant deaths could be attributed to air pollution in South East Asia alone (see state of global air report). The annual death toll from fossil fuels is estimated to be 8 million. The Open Philanthropy Project has collected further estimates on the damage of air pollution in this report.

There are also more indirect, fuzzy safety concerns with nuclear, e.g. health effects on people living close to the plant or groundwater contamination from waste. According to this summary, the radiation exposure of workers in nuclear plants and miners in uranium mines is between 1.5 and 2.5 millisieverts per year (mSv/yr) while an average citizen is exposed to about 2.4 mSv/yr of background radiation, i.e. broadly the same amount of radiation. The lowest level at which cancer rates are increased is 100 mSv/yr, i.e. much larger than what anyone is usually exposed to. Long-term storage of high-level nuclear waste is (supposed to be) done in deep geological repositories which are regarded as very safe (see below) thus not increasing radiation risk.

There are some people (see e.g. this post) who claim that most radiation standards are based on outdated methodology and thus put an unreasonably high standard on nuclear radiation when compared to literally any other health standard. While we can’t tell what the correct level of allowed radiation should be, we understand where this view is coming from. The regulatory standards for nuclear are much higher than they are for coal, gas, oil, food or medicine. Whether this is good or bad depends on your perspective, but safety regulations in nuclear energy could probably be drastically lower and wouldn’t increase harm in any meaningful way.

Our overall impression is that nuclear energy is very safe, especially when compared to fossil fuel alternatives. Most nuclear power plants have passive built-in safety mechanisms, e.g. such that cooling systems don’t break when they lose power or the chain reaction in the reactor is stopped automatically.

Furthermore, even the worst-case scenarios seem less problematic than commonly assumed. Contrary to portrayals in pop culture, nuclear power plants don’t explode like an atomic bomb. Usually, they get really hot and possibly melt down. Under specific circumstances, there can be hydrogen explosions that release some amount of toxic material. In cases of old technology and severe human error, they can make the surrounding area uninhabitable. However, this process is so slow and well-monitored that everyone can be safely evacuated in time and no human casualties occur. There are, of course, human and economic costs if an area becomes uninhabitable but the probability of such an event is extremely low. Furthermore, for the extraction of coal, the relocation of entire villages and the destruction of the environment is the norm rather than the exception.

To put it more bluntly—living next to a nuclear power plant or waste storage (especially in the West) is probably orders of magnitude less risky than driving a car and significantly better for your health than living close to a coal plant.

The waste problem

There are a lot of common concerns with waste—most prominently feasibility and cost.

Over 90% of nuclear fuel waste is low-level waste that poses little to no health risk to humans. Only 3% of the waste is classified as high-level waste. It contains 95% of the total radioactivity and thus has to be stored safely. The high-level waste is treated and transported to the final storage facility. It is (or at least supposed to be) stored in deep geological repositories (see also Wikipedia). Those are far below the surface where groundwater is devoid of oxygen which reduces the risk of contamination. Furthermore, the groundwater is additionally monitored by agencies and thus harm to humans is very unlikely. Sweden, for example, has started to build a new storage facility that they regard as a completely safe final repository after collaborating with scientists for multiple decades.

The overall cost of treating, transporting and storing waste seems surprisingly low. This overview claims that waste contributes about 5% of the total cost. This OECD report states that during deployment the entire fuel cycle (upstream and downstream) makes up a maximum of 20% of the cost. A further maximum of 15% of the total cost is used for the decommissioning process—a part of which is long-term storage.

It is important to state though, that all waste costs are supposed to be internalized, i.e. the consumer pays for them already when buying electricity. A part of the profit is then put into a fund that continuously finances the long-term storage of waste. This means that the “waste is too expensive” argument can only hold if there was a serious miscalculation of the waste cost—otherwise, you have already paid for it. If the external costs of fossil fuels would be internalized, their prices would likely increase dramatically. However, for some reason, society decided that only nuclear energy deserves this special privilege.

Unfortunately, the real world is much messier—at least in some countries. In Germany, for example, there is a very strong opposition to waste storage which makes it hard to find a suitable location. Ultimately, we think that problems like this will make waste storage more expensive, e.g. because Germany has to pay Finland for disposal. But it’s not an argument against nuclear per se since we have good and working solutions that just need to be implemented correctly.

We want to mention that opponents of nuclear would tell you that the calculations for long-term storage are misguided and thus underestimate the true cost. Therefore, future generations will pay additional money to fix problems created by us. They argue that a) governments often pay for the waste management cost that should have been internalized and b) companies use unreasonable discount rates for waste management. We think that even if their arguments were correct it would not drastically increase the cost of nuclear and could be solved by regulation reform and is thus only an argument against the status quo rather than an argument against nuclear itself.

The economics of Nuclear

The main takeaway from investigating the economics of nuclear power is that it’s very messy. However, we can observe multiple trends.

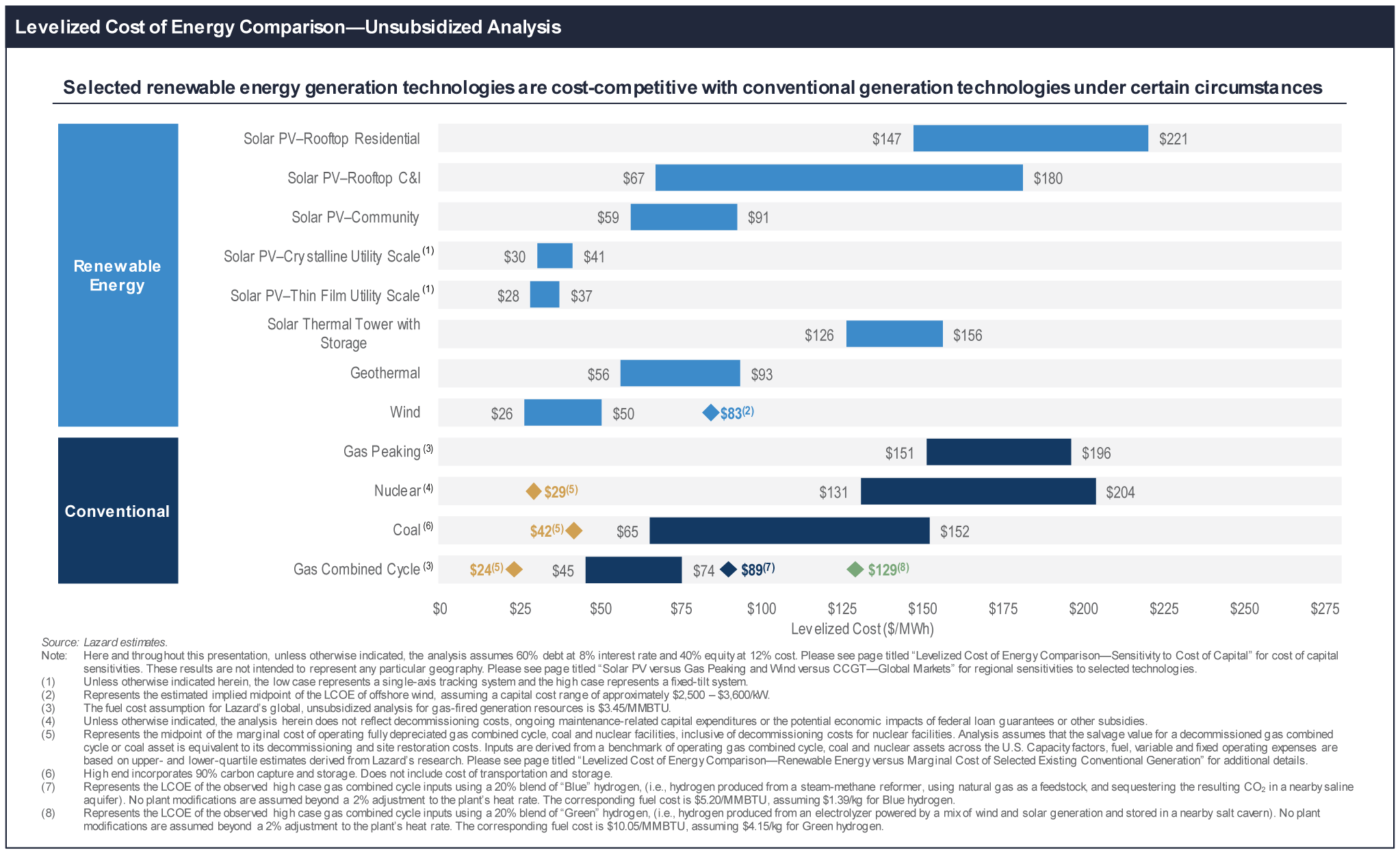

First, nuclear power is expensive compared to the cheapest forms of renewable energy and is even outcompeted by other “conventional” generation sources (“LCOE” measurements are also underestimating nuclear costs relative to other generation sources because it doesn’t take the interest that accumulates on loans every year into account. Because building nuclear power plants takes significantly longer than other plants, interest represents a larger source of their overall cost). This comes with the important caveat that_ keeping existing nuclear power plants is very cheap _and should be done wherever possible. The consequence of the current price tag of nuclear power is that in competitive electricity markets it often just can’t compete with cheaper forms of generation.

Source: Lazard

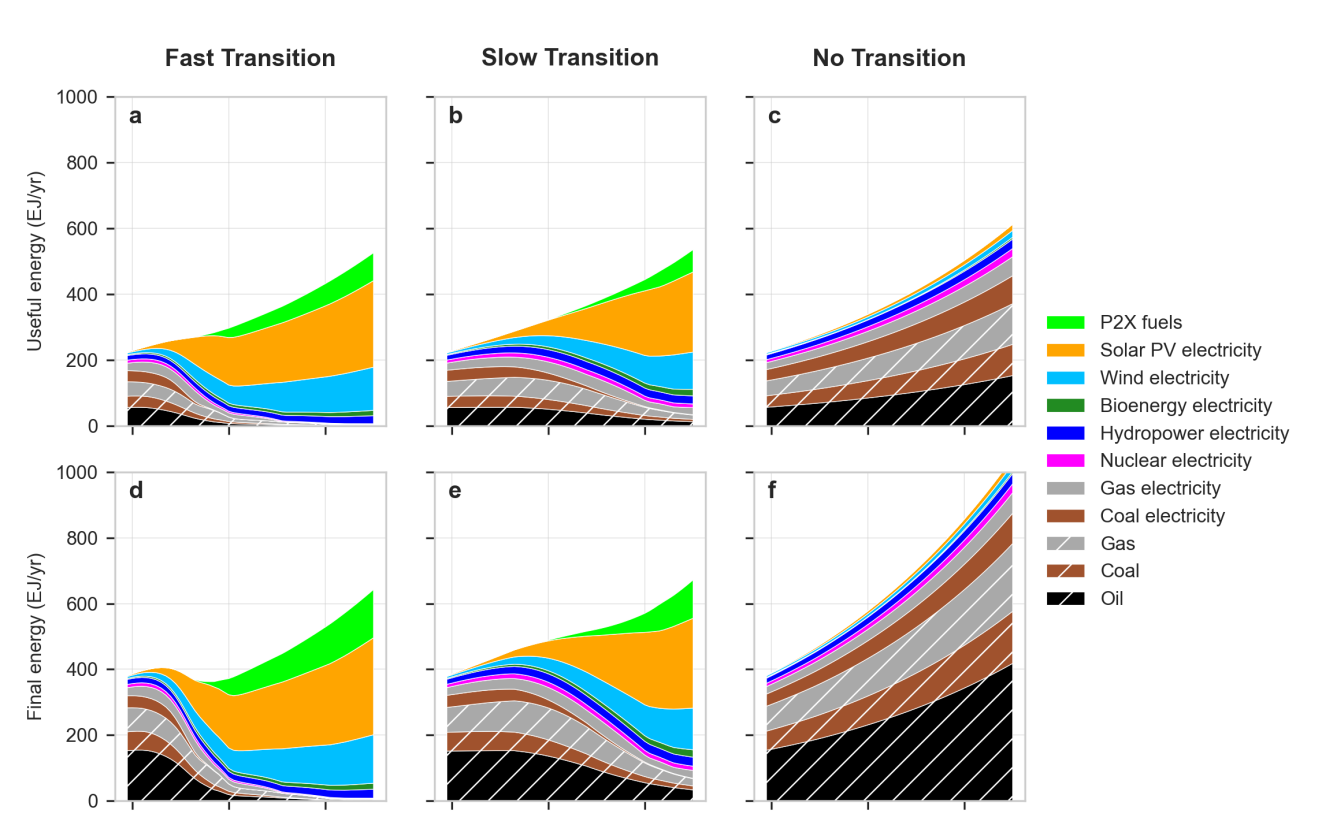

The second issue is that in the recent past, nuclear power failed to get meaningfully cheaper and instead got more expensive as different power plant projects in the US, Finland and UK experienced delays and cost overruns. As a result, when economists try to incorporate the cost curves (the amount by which a given product gets cheaper when the output is doubled) of different technologies into their electricity grid models, nuclear doesn’t play much of a role at all in the future of our grids (see figure below). This is mainly because the cost trajectories for solar, wind and battery technologies are so steep that even if a mass deployment of them is economically unwise now, it likely will be the cheapest option in 10 years. In the graph, you can see that in all scenarios which were modeled (based on what emission targets we want to hit), nuclear power either remains a constant but small part of the energy mix or vanishes completely. Forecasting the future cost of technologies obviously comes with some uncertainties but the learning rates of industries tend to be surprisingly stable over time. This means that barring any unique, overriding information we should probably bet on learning rates remaining relatively constant over time.

Having established that nuclear power is currently quite expensive and not looking to get much cheaper, the important question is why. Let’s consider possible reasons:

1. No (more) economies of scale

Most of the nuclear power plants in the west were built a long time ago with very few new projects happening in the last 20 years. This means that every single power plant has to be planned and constructed from scratch which creates expenses in long planning and approval processes. Additionally, the small quantity of projects means that it’s also not feasible to mass produce the individual components for plants which further drives up costs.

This is in many ways the opposite trend of technologies like solar panels which have seen rapid cost declines specifically because the sheer scale of production has enabled lots of small savings through standardization processes that compound over time.

2. Overregulation

Some people argue that the main reason for the cost increase of nuclear power is overzealous regulation from agencies with badly aligned incentives. We tried to see if there was any corroborating evidence, but all other sources we looked at (both pro- and anti- nuclear) did not mention over-regulation as an issue. Even the pro-industry documents say that regulation standards are very high and use that as an argument for why nuclear is safe. Apart from some specific calls around changing the regulation of prototype reactors and some regulatory harmonization, we couldn’t find this narrative of broad over-regulation anywhere else.

However, we think that some parts of the current regulatory landscape are suboptimal and there are some concrete measures for improvements. These include

- A reform of the current risk model. The current model assumes that cancer rates scale linearly with radiation which is known to be a bad model.

- Enable more testing. In the status quo, test reactors are treated like production reactors and it is thus infeasible to experiment and innovate.

- Align the incentives of regulators with the industry. The current system punishes regulators for incidents but doesn’t reward them when we produce more energy. Importantly, most regulators are not elected officials (more like examiners) and thus don’t need to keep energy prices low for their constituents.

- Allow arbitration of regulation. Currently, regulators hold a monopoly on power and it is nearly impossible to appeal a decision. One single regulator/examiner can shut down a nuclear power plant on their own and it’s nearly impossible to appeal.

3. It’s just that expensive

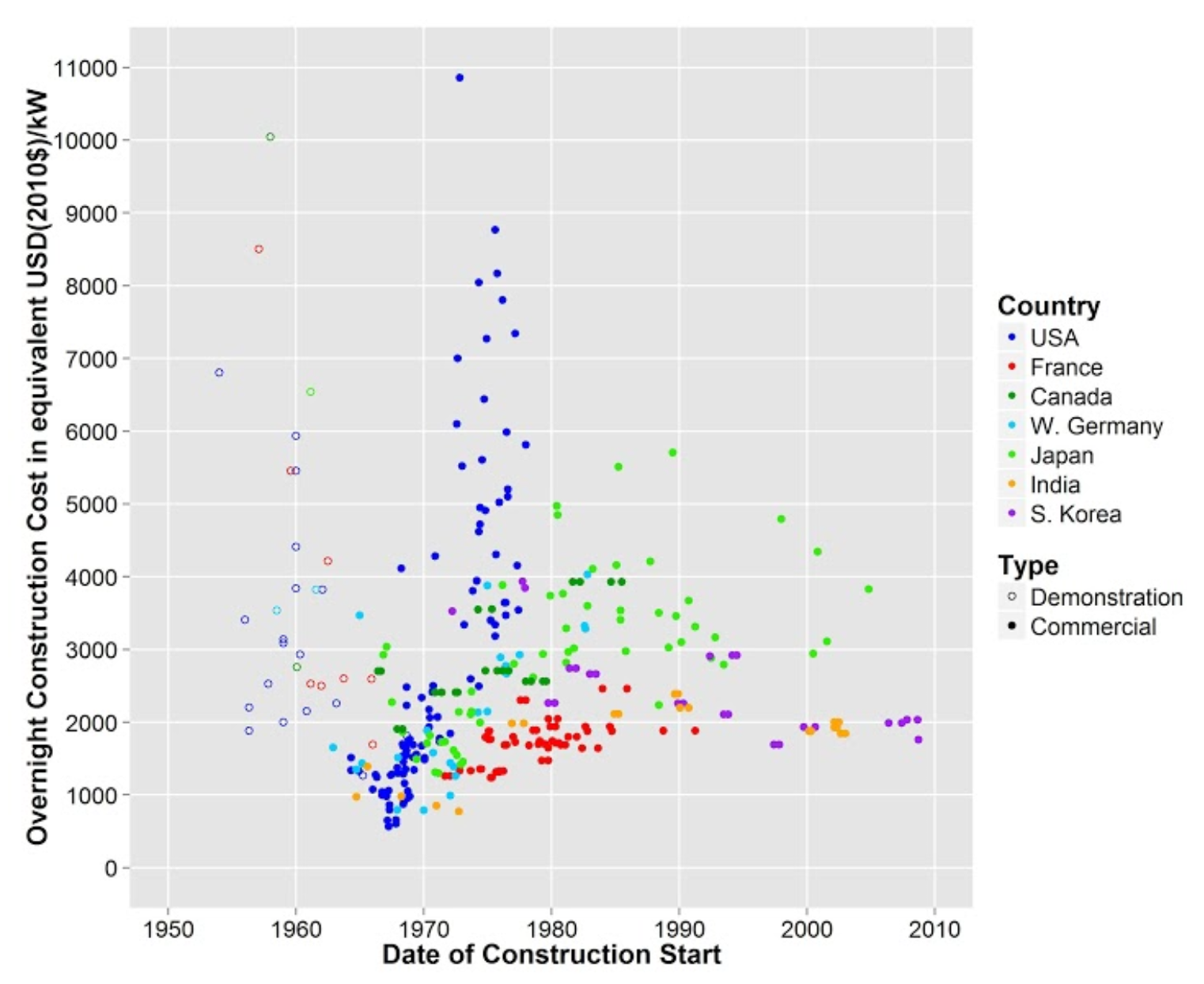

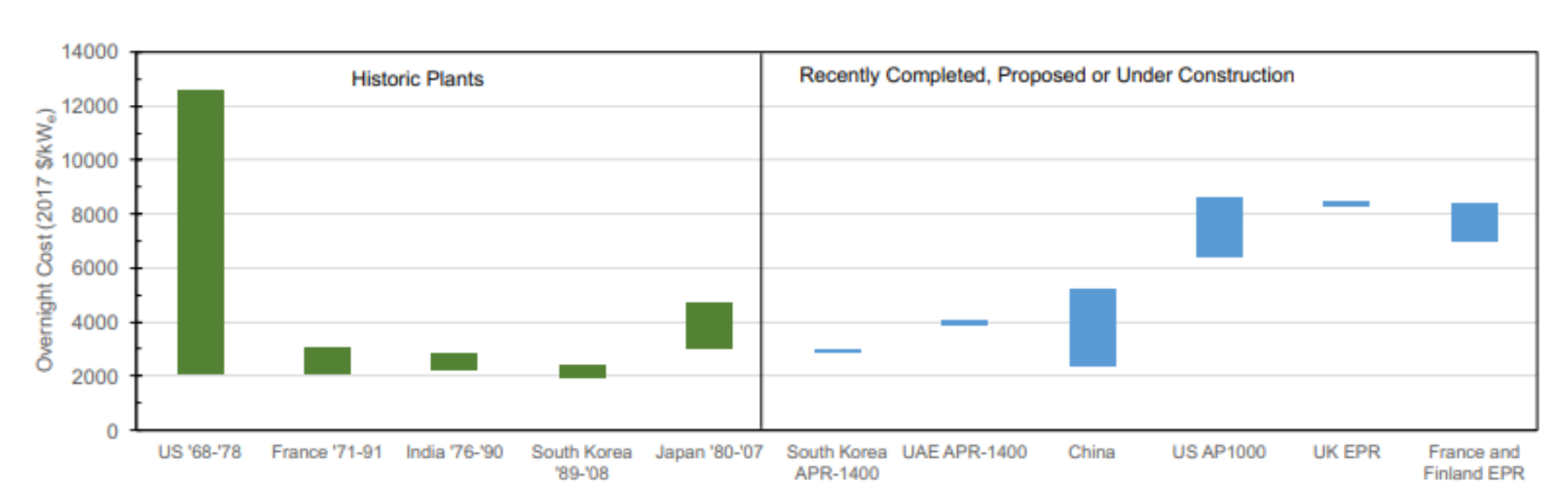

Potentially, nuclear energy is just very complicated and finicky. Combined with rising construction costs in most western countries and big capital requirements it could simply be expensive. However, this doesn’t explain the historical trend of nuclear having been cheap at some point and then getting significantly more expensive over time. It also doesn’t explain why we see a significant geographic variation in construction costs (see figure, though there are also critiques of the validity of this data).

However, construction cost figures from South Korea and China should be taken with a grain of salt. According to a professor Samuel talked to, they have strong PR incentives to make the construction costs appear competitive to secure future projects and existing transparency requirements are insufficient.

Overall, the picture remains complicated. Existing nuclear power plants should definitely be kept running, but building new ones seems too expensive for the time being. It’s unclear if costs can be brought down effectively over time. The malaise of the western nuclear industry seems deep and enduring at this point. Potentially China and South Korea have cracked the problem and with increasing deployments of power plants throughout the global south, they could leverage economies of scale far better than the industry could in the last 30 years. However, this is still early days and without a more solid track record, we can’t confidently say more.

Future nuclear technologies

If you spend enough time on techno-optimist Twitter, you will see lots of hype for molten-salt reactors, small modular reactors, even smaller and even more modular reactors and a plethora of other exciting future nuclear ideas. Most of these ideas are so early in their respective design stages that their commercial viability is completely unclear. Early estimates for their costs don’t even show them being much cheaper (the estimates themselves are uncertain and from 2012). More importantly though, with current implementation timelines, we shouldn’t expect commercial deployment before 2050. Given that we need to already have made significant progress in decarbonizing our electricity grid by then if we want to combat Climate Change, most innovative reactor technologies will simply be too late to matter in this regard.

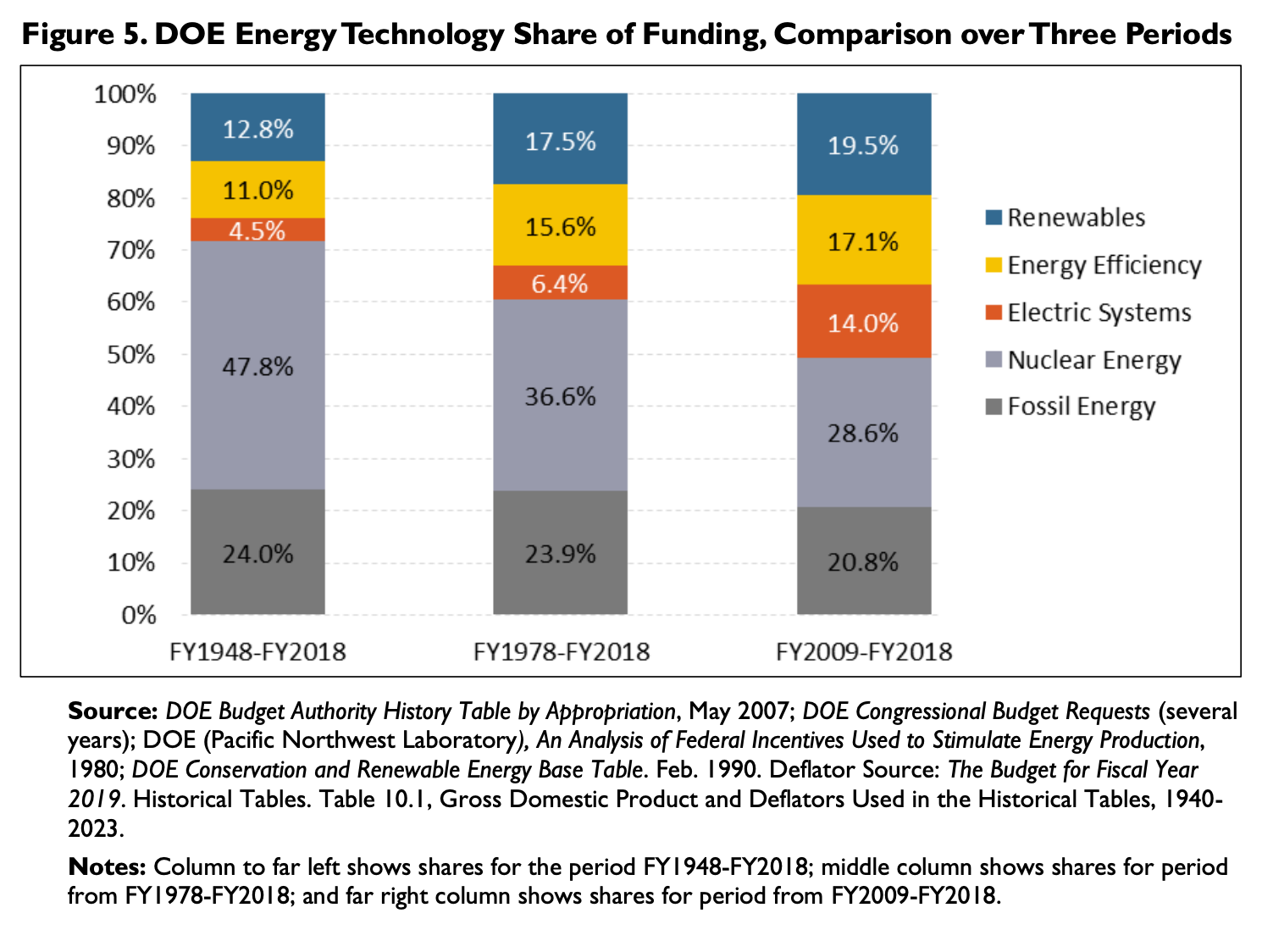

An additional important note about future nuclear technologies is that nuclear energy has consistently received comparatively large amounts of the overall R&D funding dedicated to energy. Even in the most recent time period from 2009 to 2018 when renewables were surging and almost no nuclear power plants were being built, it still got a larger share of DOE funding. Combining the amount of funding with the overall lack of progress should cause us to be more skeptical of claims that better nuclear tech is just around the corner and financially feasible.

The future tech which seems the most ready is “Small modular reactors”, which are scaled-down versions of existing reactor designs (300MW output for an SMR as opposed to 1000-1600MW output for a regular reactor). SMRs could ideally solve some of the problems around the lack of economies of scale by turning reactors into smaller, mass-producible products which could significantly lower unit costs. However, so far this doesn’t seem to be the case and the SMRs that Rolls Royce is building in the UK have relatively high unit costs (expected costs per unit is 1.8bn pounds according to Samuel’s professor). Even then, they are expected to deploy by 2035 if everything goes to plan. Most countries need to make important decisions about their electricity grid investments before then if they want to hit their respective climate goals deadlines. Therefore, even if SMRs work well, they might still be too late to matter.

The role of nuclear in a grid dominated by renewables

If renewables are cheaper than nuclear energy and the trends look like this disparity will only increase, can we just focus fully on renewables? Not necessarily, because renewable energy supply is volatile in a number of different ways. There are predictable daily fluctuations in production (lots of sun at noon, little sun in the evening), predictable seasonal fluctuations (less sun in the winter) and unpredictable semi-regular fluctuations (multi-day events of low wind).

While you can hedge against the predictable fluctuations somewhat through optimizing the ratio of wind to solar resources (the production peaks/troughs of wind and solar cancel out somewhat), seasonal fluctuations and unpredictable events remain thorny problems. This leaves us with two needs for our grids. Flexible short-term generation capacity to offset daily fluctuations and long-term stable production to offset longer time periods of supply-demand mismatch.

Nuclear power is pretty unequipped to handle the first kind of need since most reactors take a long time to ramp production up and down and because the high price tag of nuclear power means that running the reactor at anything less than its maximum production would be economically infeasible. The second need is something that nuclear power could potentially fulfill. Here the question is simply which of the available technologies (battery storage, Pump storage hydro, geo-thermal) ends up being the cheapest and most scalable.

(Disclaimer for this section: modeling electricity grids is very complicated because it combines a bunch of different sources of uncertainty. It’s also highly location-based and subject to lots of crucial assumptions about market behavior, cost curves and weather patterns. Therefore, these considerations can lead to different conclusions for different regions.)

Plausible futures

We think there are broadly two reasonable pathways for the future of energy.

Invest in nuclear, reform and innovate

As we described above, there are many reasons why the status quo of nuclear is far from optimal. The safety regulation is potentially unnecessarily high which increases the price and prevents innovation, current nuclear power plant construction doesn’t use the benefits of economies of scale and there is some research that could improve every step of the cycle, ranging from scale & efficiency over recycling to waste management.

Thus, a future with nuclear would make the necessary changes and hope that the price goes down sufficiently. However, a lot (see section on future technologies) of money has been pumped into nuclear energy research and the results have been less exciting than promised. There is, of course, some chance that previous researchers and lawmakers have had the wrong focus and a better agenda would lead to better results in the future. However, there have been many countries that financed research on nuclear energy and we think, therefore, that there is a non-negligible chance that it’s just harder/less promising than we would like it to be—especially when contrasted with its alternatives.

Invest in renewables and storage

The price of renewables has decreased massively over time. Solar power, for example, is now 99.6% cheaper than in 1976, which implies a ~200-fold reduction, and its cumulative installed capacity has been growing exponentially.

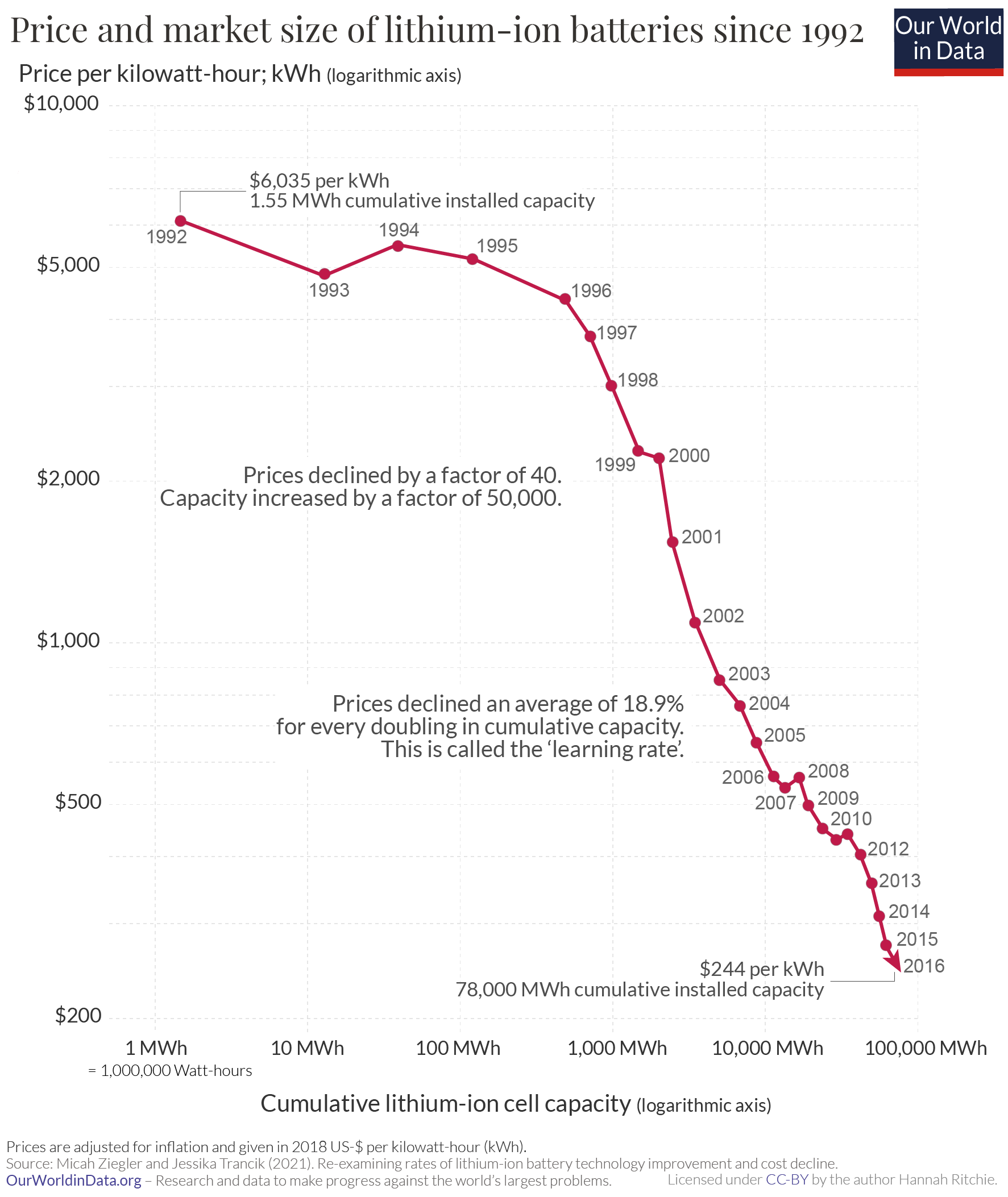

Furthermore, the price of lithium-ion batteries has seen a broadly similar trend since 1995, i.e. exponential drop in price and an exponential increase in cumulative cell capacity.

The cost of wind energy has decreased as well but not as steeply as solar. The price of energy from coal has stayed the same and the price of nuclear energy increased by about 1.5x between 2010 and 2019. Furthermore, we are now at a point where generating energy from renewables is cheaper than from fossil fuels or nuclear. The remaining downsides of renewables are a) they depend on external conditions such as wind and sun and b) the energy is generated in a different location from where it is needed and thus needs to be transported.

There are plausible ways of solving these problems though. We could build more high voltage lines to solve the transportation issue and there are many ideas to improve storage. These include really large (clusters of) batteries or decentralized solutions where the energy is stored in a large fleet of electric cars. Since stationary battery clusters don’t need to optimize for low weight, different chemicals and setups might be possible (see this start up which claims to produce utility-scale battery tech for 10% of current lithium-ion battery costs). Alternatively, the electric energy could be stored in the form of hydrogen (see e.g. [1], [2]) or ammonia.

None of these storage facilities are sufficiently well developed yet to handle a fully renewable energy system. However, the progress in renewables is moving very fast and research seems to quickly and consistently produce improved capabilities.

Conclusions

We think much of the problems described in public discourse are actually not very big. We don’t think safety is a big problem and we don’t think waste is or will be a big problem. Furthermore, one can make the case that nuclear energy is even overregulated and that safety standards are so high that they effectively prevent new plants from being built (possibly by design). We don’t know what the right level of regulation for nuclear is but it is definitely inconsistent with most other safety standards for food, medicine or fossil fuels when you compare the numbers. However, it is undeniable that the current price of nuclear energy is much higher than for renewables (~2x).

We speculate that this difference in trajectory can be explained by market conditions. It is much easier to mass-produce and standardize solar panels than the construction of nuclear power plants. Thus, we expect this gap in price to grow rather than shrink. Furthermore, energy storage such as batteries has seen very steep increases in price/capacity as well—possibly for similar reasons.

However, in almost all cases, nuclear is much better than fossil fuels. Furthermore, there might be a role for nuclear in the future. It is clean, gives you high energy independence and allows you to build energy production geographically close to where it’s used. Therefore, we think there might be a role for nuclear energy in the future just not a very big one. If we (as the authors) had to decide now, we would double down on renewables and design the role of nuclear around a future grid in which wind and solar dominate the energy supply.

We would like to thank Maria Heitmeier, Laurenz Hemmen, Peter Ruschhaupt, Emil Iftekhar, and Mona Bukenberger for their feedback and comments.

One last note

If you want to get informed about new posts you can follow me on Twitter.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.