What is this mini-series about?

The overall purpose of these posts is to build a framework to judge debates probabilistically and illustrate how some parts of adjudication work within this framework. Part I dealt with a single argument made by a team in a vacuum. This part deals with direct interaction, i.e. some kinds of rebuttal and some extensions. Part III will deal with the overall comparison between different arguments and metrics. As already emphasized in the first part, I want these posts to be as understandable as possible even for people that do not have any background in statistics or math. If you do not understand a certain explanation please let me know. If you have understood the explanation but think it is an incorrect model of debating please let me know as well to improve the model.

Part II: Interaction

The two kinds of interactions I want to focus on in this post are direct rebuttal and some extensions.

Direct Rebuttal

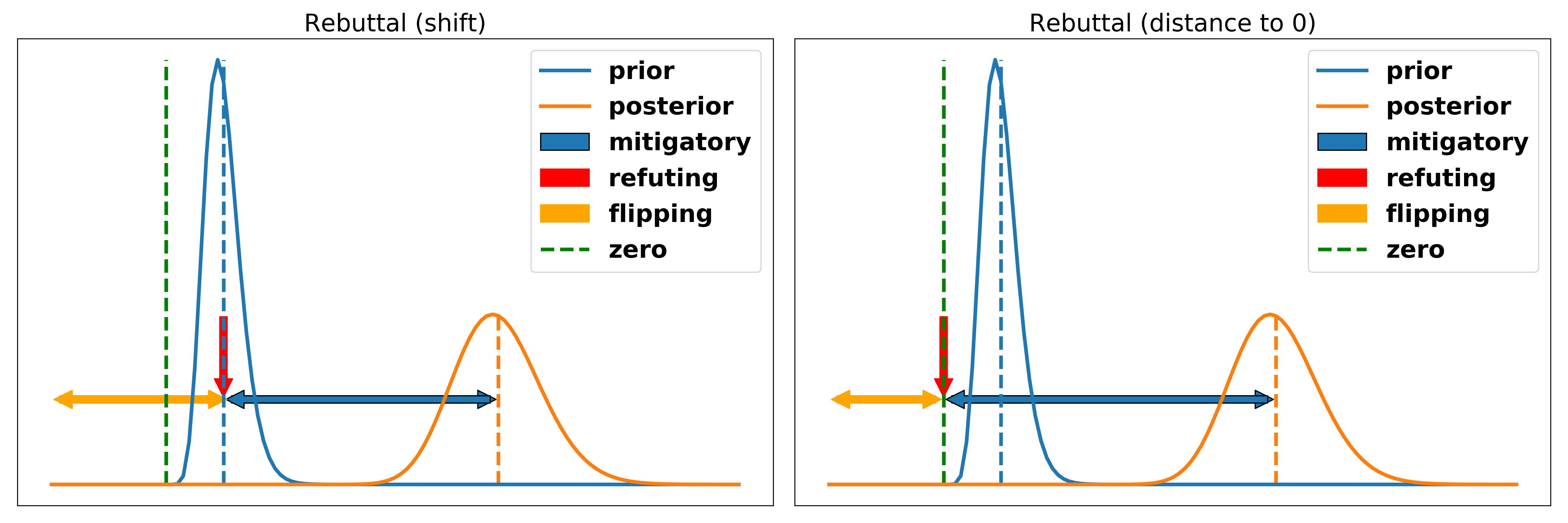

We often distinguish between three kinds of rebuttals. Rebuttal that is mitigatory, rebuttal that refutes an argument and rebuttal that flips an argument. I think that these categorizations merely describe different sizes of the same concept, namely rebuttal. This becomes clearer when considered with the probabilistic framework. Rebuttal is merely a description of an argument that directly responds to another argument that has already been made in the debate. You can think of the rebuttal as removing persuasiveness of the argument being responded to. If you remove less than the entirety of the argument’s persuasiveness we call it mitigatory if you remove the entirety we call it refuting and if you move the slider more than 100 percent we call it flipping rebuttal. Of course, there are additional possibilities to deal with the argument of another team like framing the argument out of the debate. However, these techniques do not deal with the argument directly but rather tell me to care less about the overall clash on which it is based. For example, a team could claim that “even if that argument is well made and people die, this debate is more about a principled question because of XYZ”. In this part of the illustration, I want to focus on the kind of ways to rebut an argument that directly engage with it instead of framing it out of the debate.

Assume that your opposing team has made the claim that a narrative of the american dream leads to more redistribution in society. The reason they give for the truth of the argument is: “people who believe in the American dream are more likely to work hard and therefore climb up the income ladder. Since they know the situation that their old community is in they are likely to give money to their friends and family, pay for schools and kindergartens in their old neighborhood.” So before the interaction of the opposing team we have the following belief about their contribution.

Let’s now consider different ways an opposing team could deal with this argument and what it would mean in the probabilistic framework.

Mitigatory rebuttal:

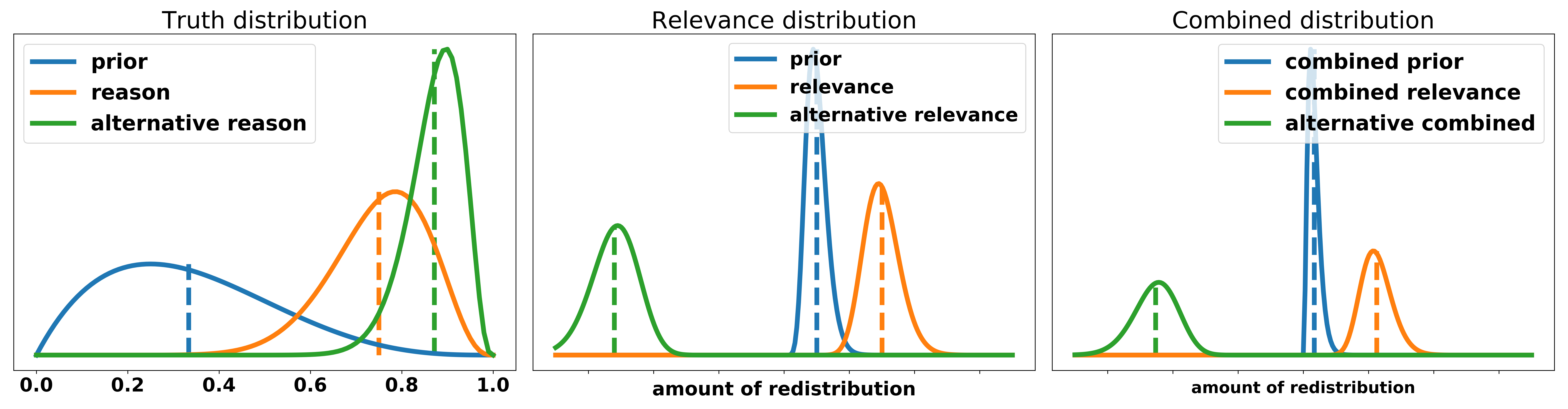

This includes any form of saying: “Your argument is overall correct but it is less true or less relevant than you made it look like”. In the American dream example we could mitigate its truth value in many ways of which I want to illustrate one: “People are to some extend greedy and egoistic. If they acquire a lot of new wealth they are often reluctant to give it away and rather spend it on luxury goods than giving back to the community.” Similarly we can mitigate the effect of the remittances in a variety of ways. Again, I want to lay out one in particular: “The money that goes back to the family and friends is spent in bad ways. Instead of people investing in their future or upgrading education for their kids they use it to gain short term gratification by buying expensive cars and watches that have fast loss of value.” To illustrate these forms of mitigatory rebuttal consider the following figure.

Refuting rebuttal:

This includes any form of saying: “Your argument is either not true or not relevant at all”, and thereby reducing the overall effect of it to zero. To illustrate a refutation of the truth value of the argument consider this answer: “The core belief of the American dream narrative is that everyone is responsible for their own success. If someone made it but others did not then it was because they are lazy and therefore not deserving of your new riches. Therefore this person is not willing to give any money back to their old community, ergo no redistribution.” We could also try to refute the effect of remittances entirely by trying to argue that every single dollar gets spent on hookers and drugs but I think this is very unpersuasive. For the illustration, just assume that a team found a way to convince you that this form of money transfer is entirely without effect.

Flipping rebuttal:

This includes any form of saying: “Either the premises of your argument are wrong and if you take the correct premisses the arguments is on our side, or the effect you are describing are actually desirable for our side because of XYZ”. If successfully executed, flipping an argument not only means the other side overexaggerated or made a wrong claim but that they have made a claim that is, in fact, harming them and helping us. In the case of the American dream debate a response that flips the argument could look like this: “If a society adopts the narrative of the American dream people are more likely to believe that their own success is a result of their hard work. They also believe that the inverse holds true, i.e. people who are not successful are that due to their own laziness and failures. They will vote for politicians that introduce less redistribution and lobby for their policies. Therefore, in total, a narrative of the American dream leads to less redistribution within a society.” This form of rebuttal is harder to fit in the truth/relevance framework since it shifts the original truth distribution to zero and also introduces a new more plausible hypotheses for the given claim thereby shifting the resulting distribution over the effects in the other direction.

Extensions

Broadly speaking there are two kinds of extensions that directly interact with an argument made by the opening half of the bench. I will call them analysis extension and impact extension. There are clearly more ways to extend an opening team from closing half, such as making a weighing to solve opening half’s open question, introducing a new argument or reframing the debate. These will be dealt with more explicitly in part III. In this part I want to focus specifically on the two kind of extensions that use an argument made in the opening half and try to extend it.

Analysis extension:

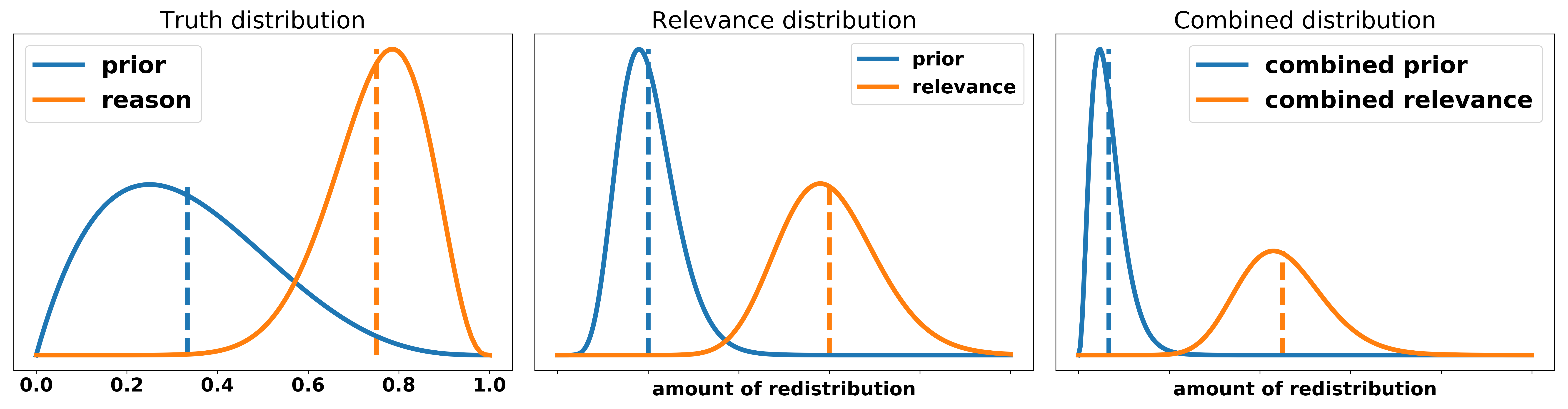

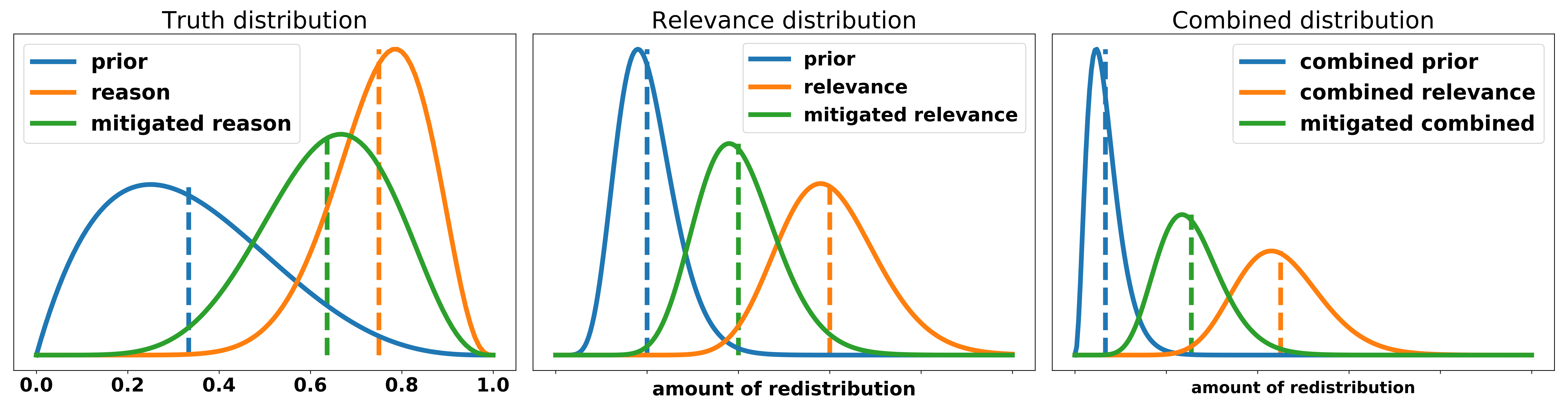

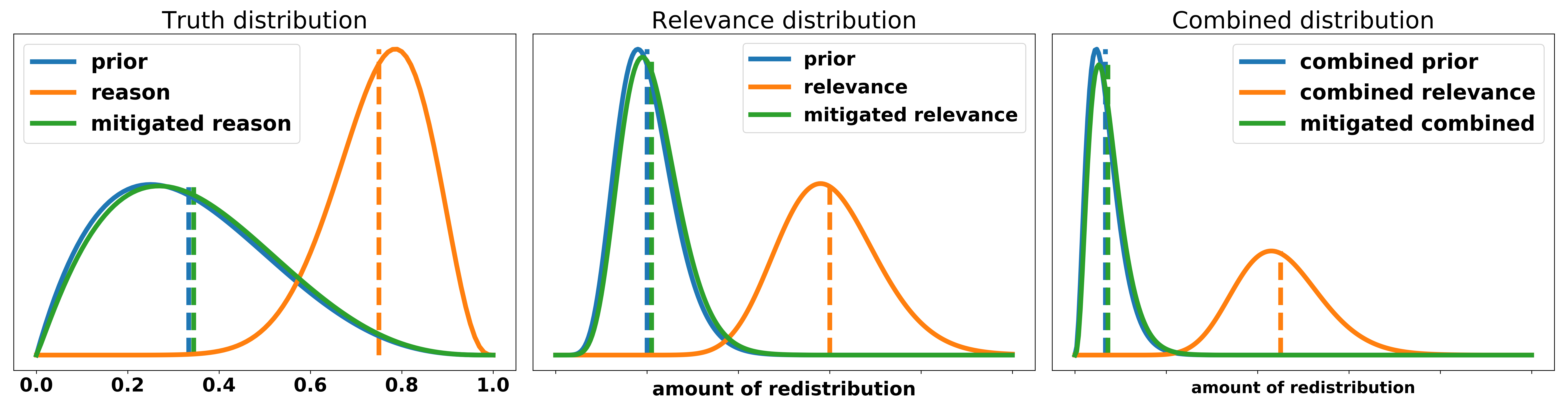

Even though the term analysis extension is used in different manners in contemporary debating, I will use it to describe every form of extension that adds reasons to shift the truth distribution of a given argument.

To illustrate this we reuse the UBI example from part I. To recap - four different reasons were given: an emotional story (weak evidence), some statistics without further explanation (mediocre evidence), a mechanism why money helps people in general (mediocre mechanism) and a mechanism that describes the fear and problems attached to an uncertain and unstable financial future (stronger mechanism). Let’s consider different possible scenarios:

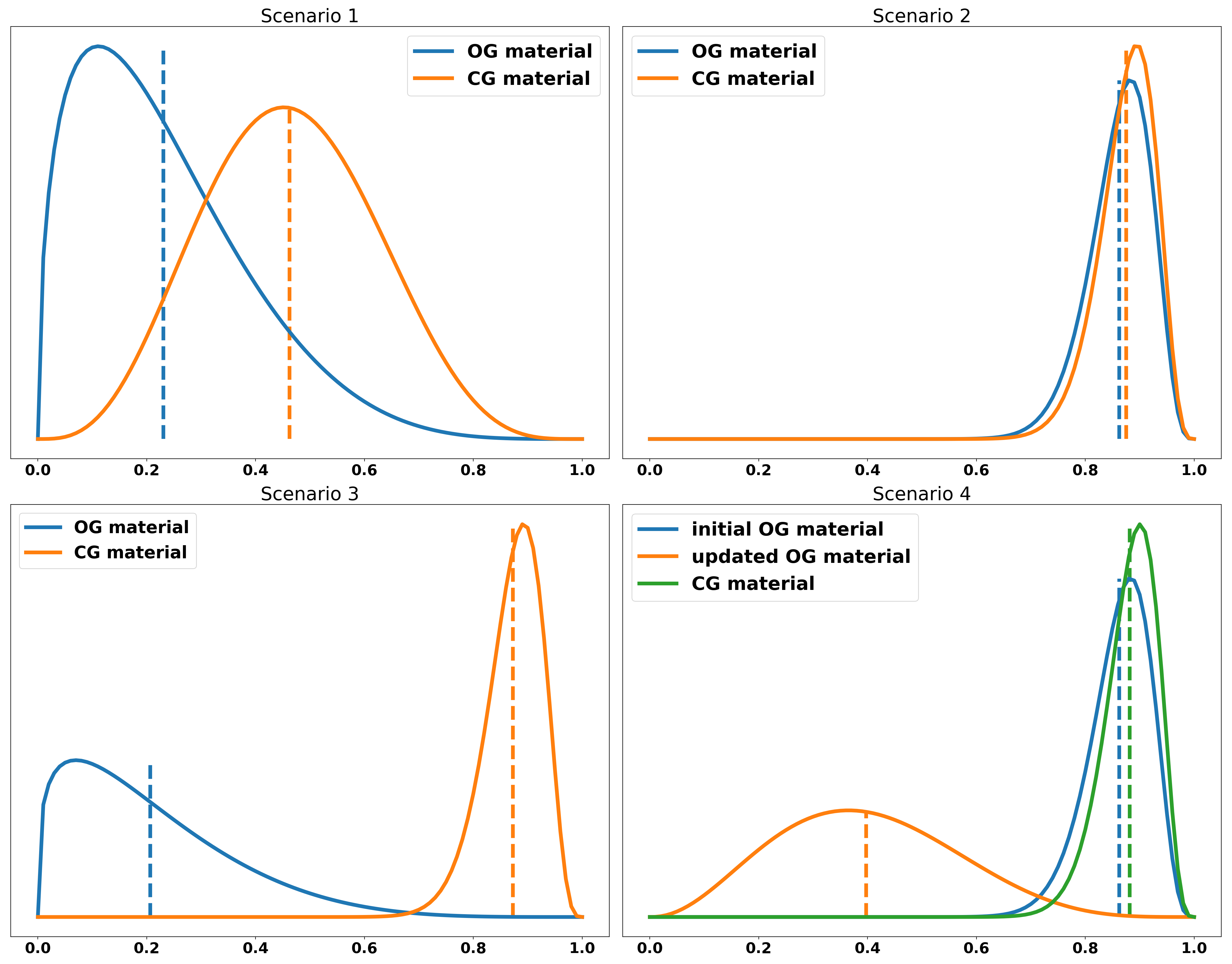

- scenario 1: OG posits that the introduction of a UBI improves people’s lives and supports this claim with the emotional story. CG extends by giving the mediocre mechanism.

- scenario 2: OG posits the thesis and supports it with the strong mechanism. CG extends by running the weak and mediocre evidence and the mediocre mechanism.

- scenario 3: OG posits the thesis but does not add any reasons why we should believe in it. CG runs the mediocre and stronger mechanism.

- scenario 4: OG posits the thesis and runs the strong mechanism. CG runs the mediocre mechanism but additionally explains why the weak mechanism is, in fact, more convincing than what we labeled the “stronger mechanism” since they show some important flaws of OG that they are able to fix.

In the just presented scenarios, assuming that the distributions over the mechanisms are correct, we would reach the following conclusions: Scenario 1 is up to execution. OG changes our belief to a certain amount and CG changes it to a similar amount, considering OG has already spoken before them. If CG has made no attempt to explicitly weigh their extension against OG, I would call it for OG. In scenario 2 CG makes a less compelling case than OG, therefore clearly losing the bench. Scenario 3 is a clear extension from CG and they, therefore, win the bench. In scenario 4 CG presents arguments that show the flaws of OGs arguments and is able to fix them persuasively. Therefore they should win the bench.

Impact extension:

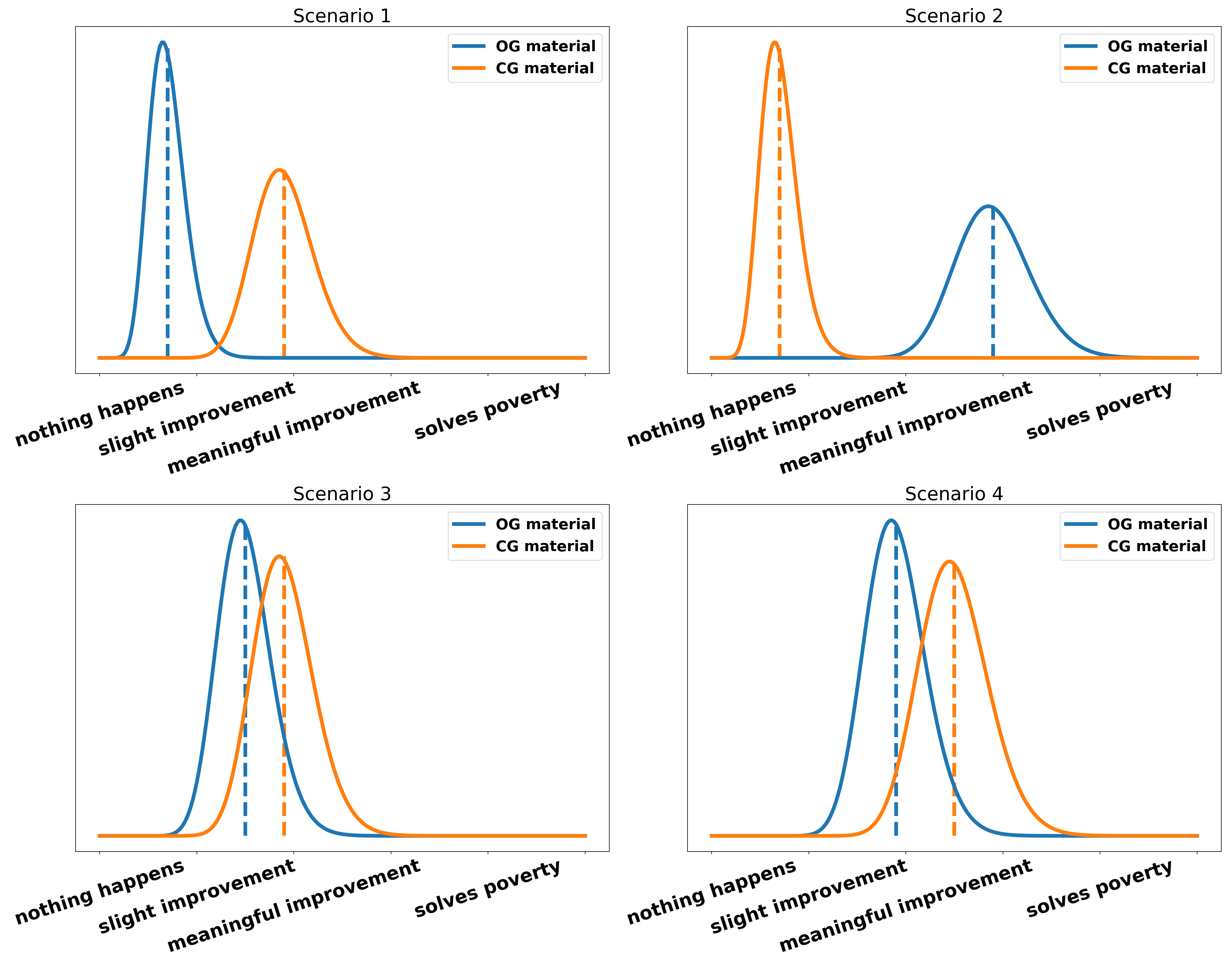

I will call every form of extension that gives reason to shift the relevance distribution of an argument impact extension. Let’s again reuse the UBI example from part I. We had: a small amount of people is being helped, a large individual effect, a large amount of people is helped and a special actor is affected. We consider the following scenarios:

- scenario 1: OG posits that the introduction of a UBI helps a small number of people, e.g. middle-class families can afford an additional holiday per year. CG extends by explaining that a large amount of people is helped.

- scenario 2: OG posits that the introduction of a UBI helps a large number of people and the individual effect is large. CG extends by explaining why a small amount of people is helped (middle-class additional holiday) in more detail without providing explicit weighing to OG.

- scenario 3: OG posits that the introduction of a UBI has large individual effects. CG extends by explaining that the amount of people helped is large.

- scenario 4: OG posits that the introduction of a UBI helps a large number of people. CG extends by explaining that UBI helps a specific group of people especially and that they are a vulnerable group and therefore especially important. (They do not just state this, they also explain convincingly why this vulnerability is something we should care more about than the number of people affected)

In the just presented scenarios, assuming that the distributions over the mechanisms are correct, we would reach the following conclusions: In scenario 1 CG clearly wins the bench since their group is much larger and therefore their effects as well. In scenario 2 CG is unable to extend since their group is a minor subset of the group already claimed by OG. No work is done to show why that group is of special importance. In scenario 3 it is up to the execution of the individual teams. If one shows their effect more convincingly then they should win. If they provide a similar level of analysis OG should take the win since CG has the additional burden to distinguish their contribution from OG. Scenario 4 is again up to execution but I think in most cases we should lean to CG because they explicitly use the vulnerability of the group as a criterion to take it over OG. Note, that the comparison between the teams is less straight forward than for the truth distribution because the scale of the x-axis is not linear, i.e. a meaningful improvement is probably not just twice as good as a slight improvement and solving poverty is not just twice as much as a meaningful improvement. At least in the given scenarios, we can think of the relevance distribution as being presented on a log-scale.

Rebuttal as Constructive

Assume the following scenario: OG makes a weak constructive point. OO makes a strong constructive point. CG does a lot of very strong mitigatory rebuttal on OO. If we assume rebuttal is constructive, we would say CG beats OG. However, CG has not made any arguments to make us believe MORE in the goodness of the motion. They have just make us believe LESS that it is a bad idea. Should CG beat OG? The answer to this question depends on your view on the Prior shift vs. Distance to zero debate discussed in part I. If you think that shift is the correct way to measure contribution CG should beat OG and OO since they have contributed more than OG and beat OO in direct interaction. If you believe that the distance to zero is the correct way to judge then CG loses since they have not been able to give a constructive contribution to the debate. I think that the shift model should be how we judge rebuttal as constructive since it better fits debating as a sport. It is not necessarily focused on truth but rather on rewarding teams for their successful effort in convincing the adjudicators of something.

Limitations of the model

-

Extensions are weird: I think there are some scenarios that are harder to account for in this framework and fixes have to be artificially introduced to make it work. Assume we are in a government agency fighting the spread of CoviD-19. A disease expert explains to us in much detail how their model works, what assumptions it makes and what the effects of the predictions mean, etc. An intern points out that there is a typo in the program and a constant should be 3 instead of 1. This little typo changes the predictions of the model entirely and also the strategy of the government. Due to the intern spotting the typo three times as many people could be saved. In the real world, we would assign a lot of credit to the intern for finding the mistake and therefore saving three times as many people. In debating, assuming the expert is an opening team and the intern a closing team, we would often say something along the lines of: “Opening provides all the mechanisms and explanations and closing only adds a minor detail, therefore opening wins over closing”. The contribution of the closing is often treated as less important because “only saying that openings group is larger than they thought without adding new mechanisms is an insufficient extension”. I also believe that this is the correct way to judge debates since debating is more a game of logic than a game of numbers. Just something to keep in mind when considering the probabilistic adjudication framework. If you disagree or think I misunderstood something please let me know.

-

Willingness to interact is not counted: The willingness to interact includes taking POIs from opening as closing and vice versa, doing rebuttal on your opening as closing or providing explicit framing for your extensions. So far I have not found a way to explicitly include this concept into the model. However, I think it is not much of a problem since framing and responsiveness are implicitly included in the truth and relevance distributions already and the POIs can be used to tip the scale if two teams are very similar in their persuasiveness.

Nerd section: some statistical explanations

- most mathematical background is similar to part I. For the flipping rebuttal I mirrored a gamma distribution at the y-axis to be in the negative domain.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Julian, Samuel, Bea, Maria, Marion, and Anton for the fruitful discussions, elaborate feedback and grammar-nazi skills (probably still contains some typos though).

One last note:

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.