What is this post about?

I have increasingly encountered two strains of thought. Firstly, that economic growth and climate change are necessarily interlinked, and thus growing the economy will always destroy the environment. Secondly, an active call for degrowth, i.e. an active promotion for measures that reduce global GDP to save the planet. While I can understand the intuition that some forms of economic activity lead to climate change, I think it is very harmful to pretend that this is written in the stars without the possibility of change because economic growth has been arguable the best thing to ever happen for poverty alleviation.

Thus, I want to answer four simple questions in this post: a) How linked is economic growth with climate change and resource use? b) How important is economic growth? c) Can alternative economic systems solve the problems of climate change? d) What policy implications follow from the previous points?

There are a lot of different resources I read for this post, but, as always, Our World in Data made my job much easier by providing excellent figures for most of my questions.

If you think I got something wrong or want to provide feedback, don’t hesitate to contact me.

Summary

We all agree that climate change and excessive resource use are bad. Additionally, we would also say that being poor is worse than being less poor - especially if you don’t live in a first-world country. Thus, we should not strive to reduce economic growth but to ensure economic growth without global warming and excessive resource use.

- Climate change is bad and current trajectories don’t come close to a solution: Even though some economies transition to renewable energy and the service sector increases in most countries, the current trajectory is not even close to meeting any relevant climate target.

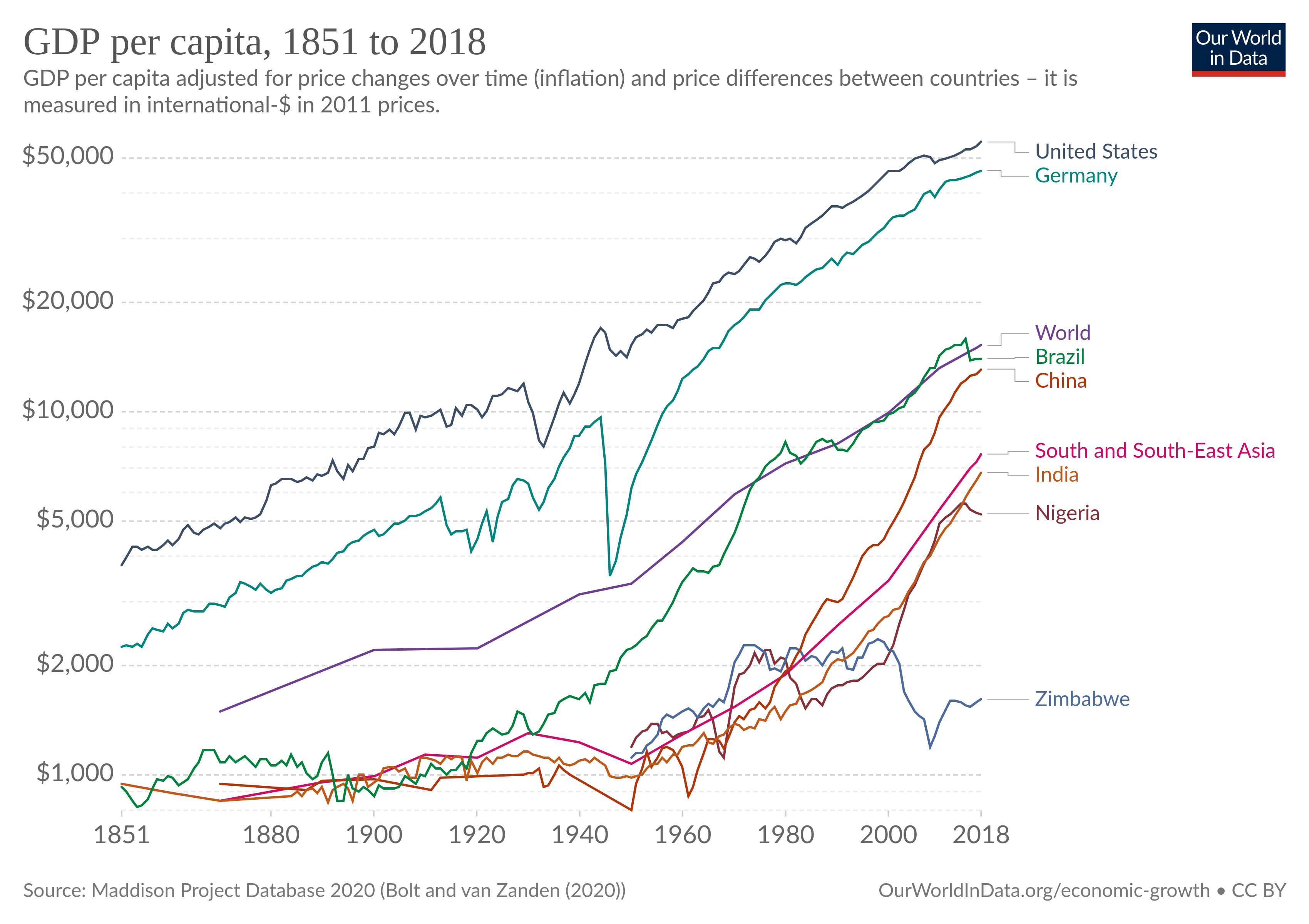

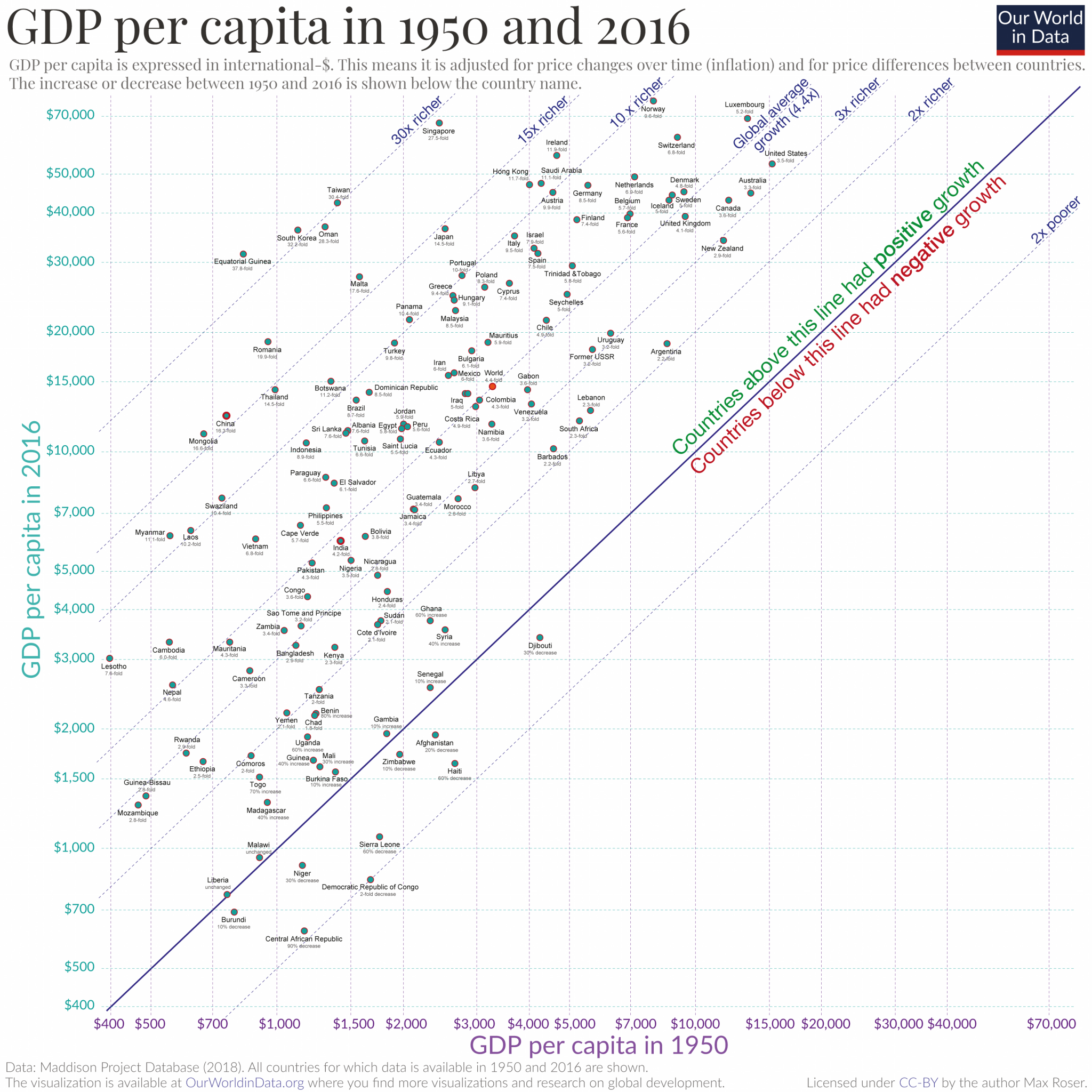

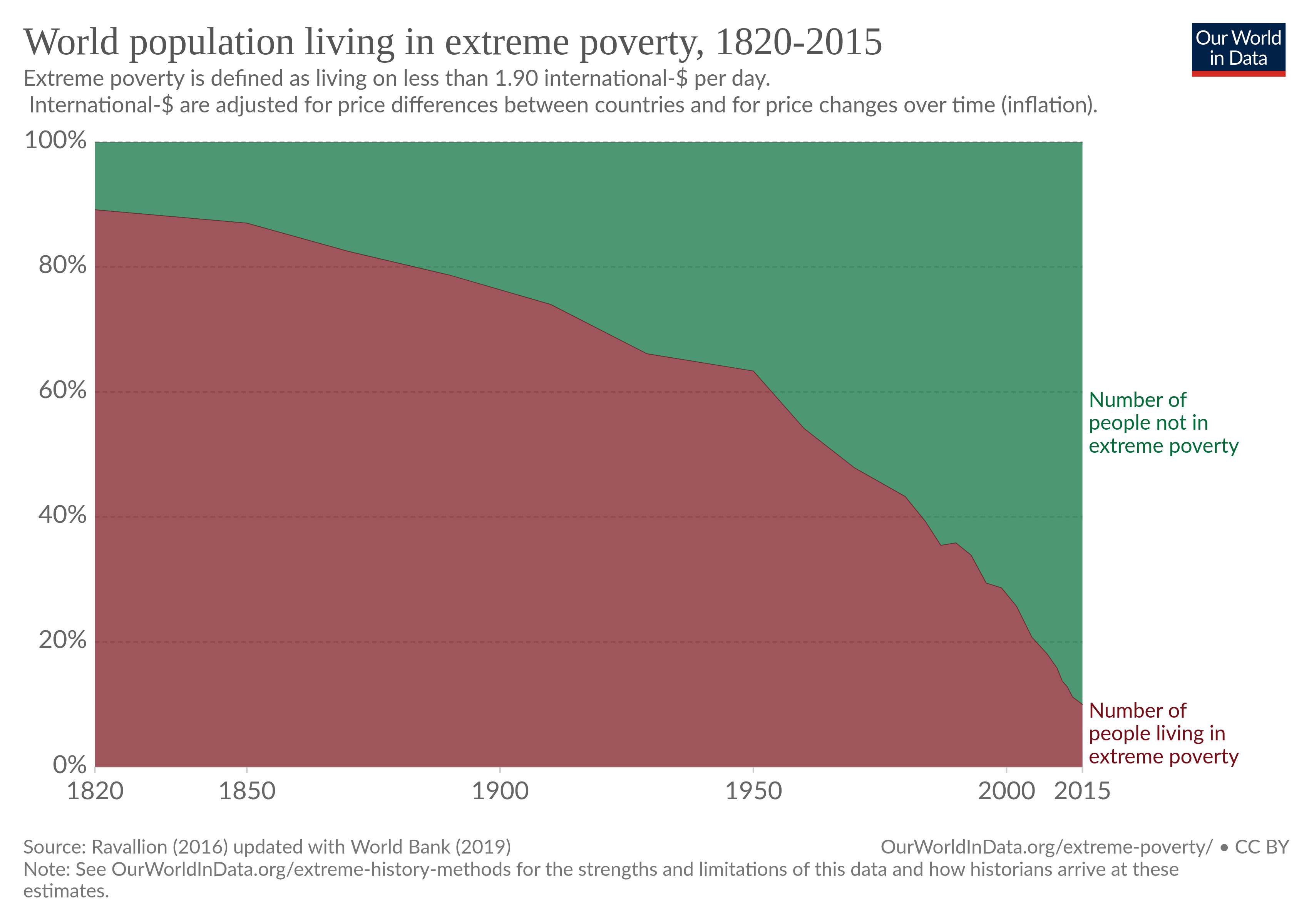

- Economic growth is really good: It has reduced absolute global poverty from 90% to 10% of the world’s population over the last 150 years. These numbers account for inflation, differences in countries, and purchasing power parity. Thus, it is fair to say that the average person today is much richer than a high upper-class person (e.g. top 5%) 100 years ago.

- It seems possible to decouple economic growth from CO2 emissions: Many Western countries already see absolute decoupling, This will likely happen through a transition to green energy and away from production-heavy industries to e.g. service economies. Up-and-coming nations such as China already see a relative decoupling. However, since the majority of people live in less developed countries, solving climate change is very dependent on the speed of their transition to clean energy.

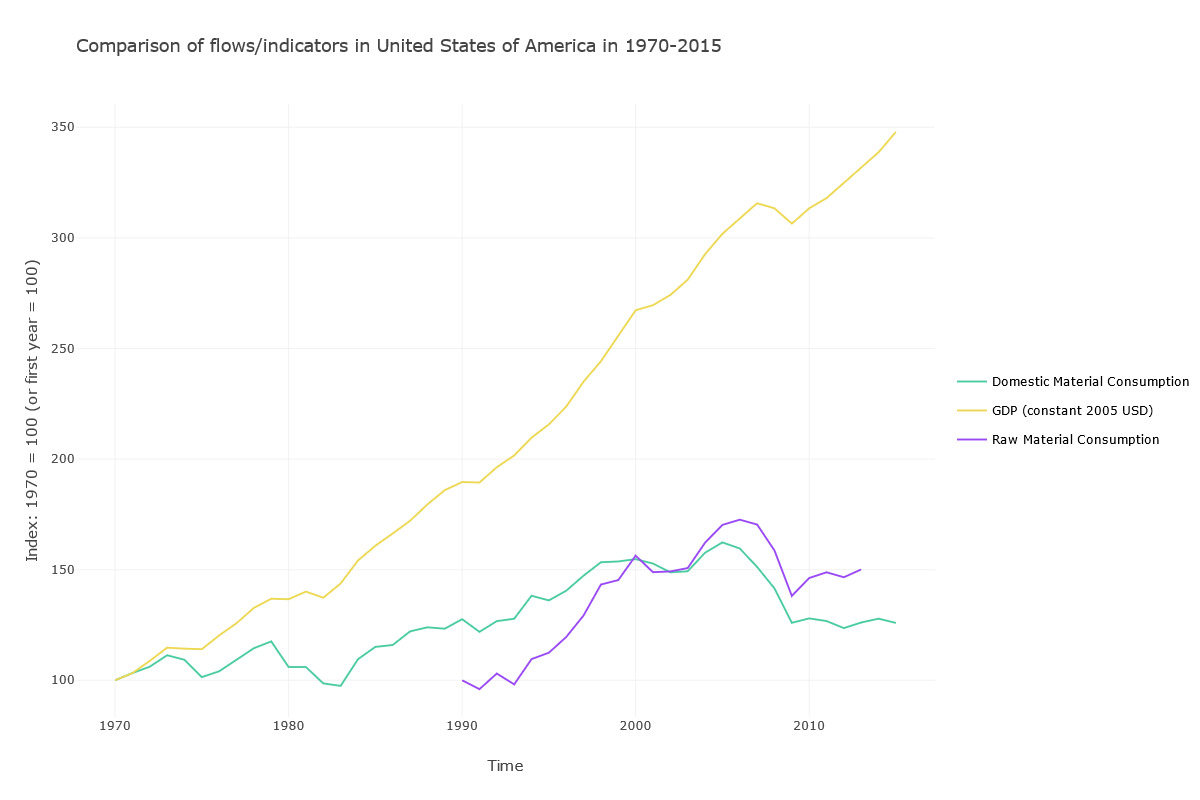

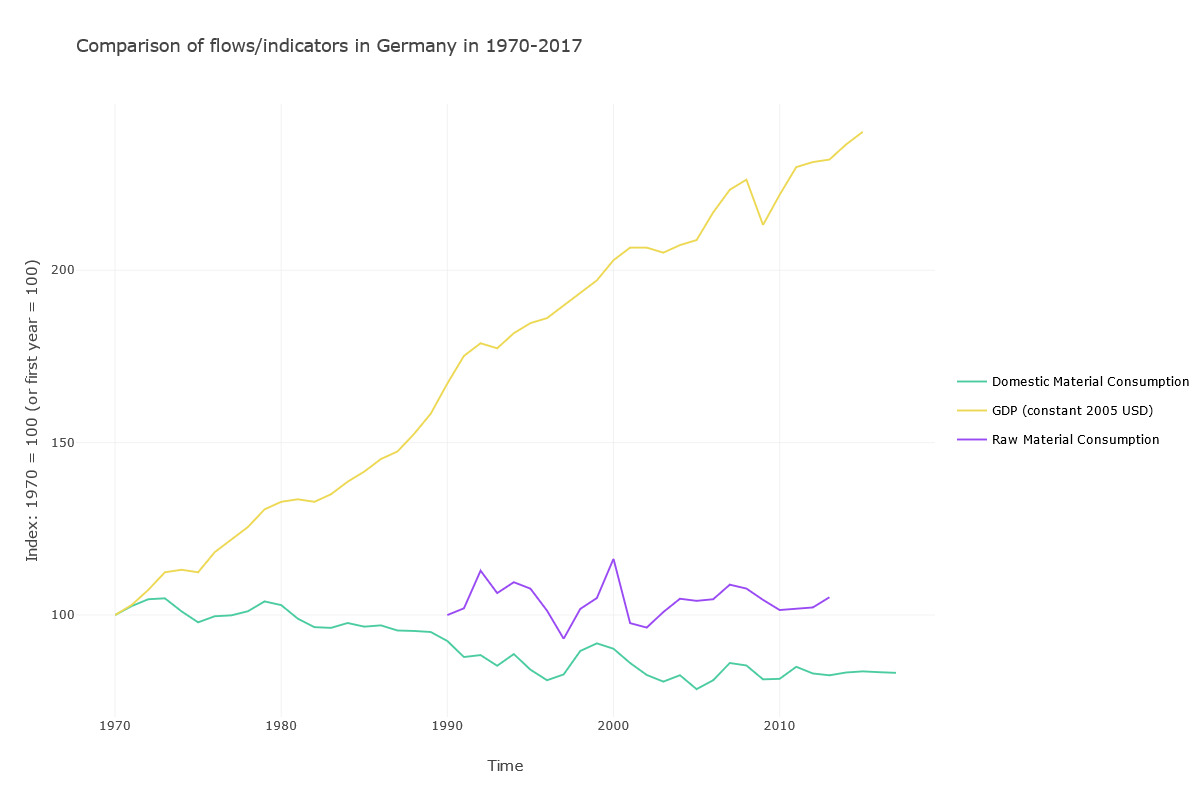

- Resource use has never been absolutely decoupled from economic growth: The use of resources such as rare earth, metals, sand, cement, etc. has historically not been absolutely decoupled in any country. Some developed countries such as the USA or Germany have seen relative decoupling.

- Massive investments into green energy and pricing schemes for CO2 are necessary: These strategies can include CO2 taxation or emission trading. Given that the time is ticking, the investments should be very large, i.e. in the hundreds of billions of dollars. These investments would likely also boost the economy and thus partly pay for themselves.

- Alternative systems such as degrowth provide important insights: From my understanding there are different conceptions of degrowth. There is strong degrowth, which argues that only decreasing global GDP can stop climate change. The strong degrowthers leave too many important questions unanswered and I thus don’t give them much credence. Then there is soft degrowth, which argues that an economy is always maximized for multiple metrics and currently we drastically overvalue economic growth over, e.g. reducing resource use, pollution or social inequality. I find this very convincing because it accepts that economic growth is good and merely argues that it has to be one of many considerations instead of the only one.

How linked is economic growth with climate change?

Before we dive into real-world data, I want to pump the intuition why, at least in theory, economic growth is not necessarily proportional to CO2 emissions, i.e. a 5% increase in GDP doesn’t necessarily imply a 5% increase in CO2 emissions. In theory, they could be just 1%, 0% or even negative, depending on the way in which this economic growth is generated. To make this more intuitive, consider the following examples. Note that these are not arguments for why economic growth is good but merely that economic growth and emissions are not necessarily linked.

In the literature on the relationship between economic growth and decarbonization, this idea is known as decoupling. First, there is relative decoupling which is when an increase in economic growth is larger than the corresponding increase in emissions. Second, there is absolute decoupling which is when an increase in economic growth corresponds to a decrease in emissions.

-

Amish people: The Amish work, create goods, trade goods, use currency and educate themselves. They do a lot of things that create value and thus contribute to GDP but they rarely use any non-renewable resources. All CO2 they create, e.g. from the fires to heat their homes, is from trees that will be regrown. Thus their lifestyle is mostly carbon neutral even though it generates economic value. It is also very likely that the Amish economy is growing quite drastically since a) their population has grown from 5000 to 340000 over the last 100 years, and b) while they might not use technology, their work routines probably still get more efficient over time. Obviously, this is not an example for infinite growth, as the Amish are still constrained by land and resources but merely an argument for why economic growth does not necessarily imply more greenhouse gas emissions.

-

Economic growth from the service sector: Especially in the developed world a lot of GDP is created from the service sector. Many of the services we use online, most of education, and entertainment count towards the service sector. Obviously, the service sector is not carbon neutral - you need to get to the hairdresser, they need new scissors every now and then and your computer or TV need energy. But the overall energy they consume is much smaller than the economic value they create compared to other sectors. Furthermore, if the energy your computer needs comes from renewables, you create economic value mostly without contributing to climate change.

-

Economic growth from climate change prevention: There are a lot of things that grow the economy and decrease global warming. If you plant trees where no trees were before and you sell half of them, you have effectively decreased the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere while increasing GDP. A company that successfully builds solar panels, wind turbines or some form of carbon storage creates jobs, generates revenue and inevitably increases economic growth while also reducing overall CO2 emissions - at least in comparison to the technologies they replace.

All of these are just isolated examples but I think it’s important to realize that economic growth does not causally imply more climate change in all cases. I also want to point out, that these examples are limited to climate change and don’t make a statement about resource use or land use in general.

However, it could still be the case that in the real world the two are strongly correlated. To investigate this we have to look at data.

Decoupling - the data

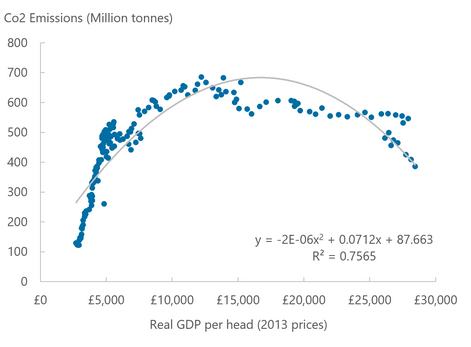

Globally, CO2 emissions and GDP per capita correlate very strongly. This implies that - at least so far - decoupling has not happened.

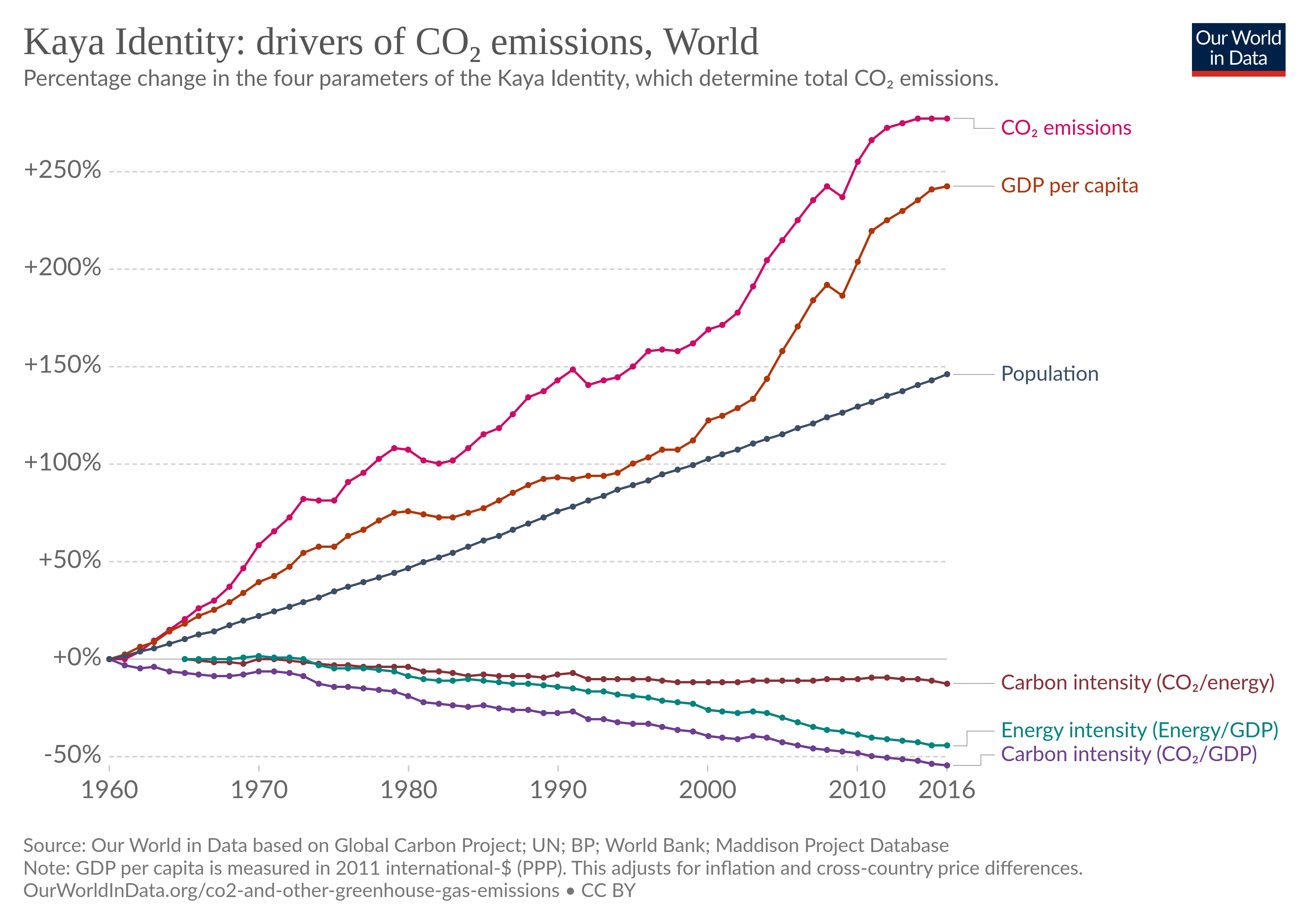

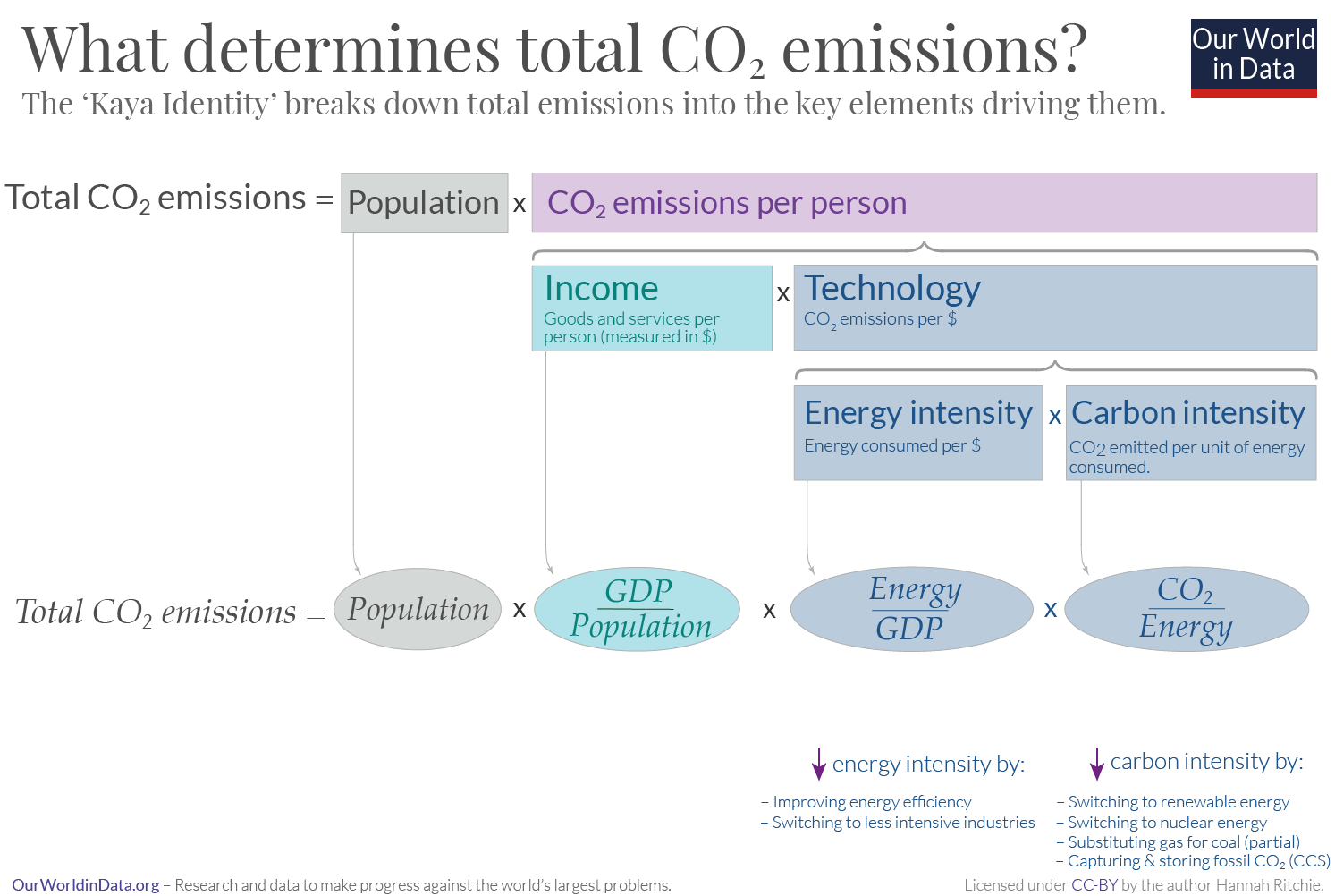

The Kaya Identity splits up CO2 emissions into their key elements.

Looking closer at the drivers of CO2 we see that carbon intensity and energy intensity have both decreased over time, i.e. growing GDP is less energy/carbon intensive than it used to be. Unfortunately, the slope of these two curves is very flat compared to the world’s population growth. Thus the overall CO2 emissions are still rising.

So at this point, we must conclude that globally a decoupling of GDP and CO2 has not happened yet. However, if we look at specific countries we see that, at least in more developed regions, even absolute decoupling is possible.

Case study - the USA

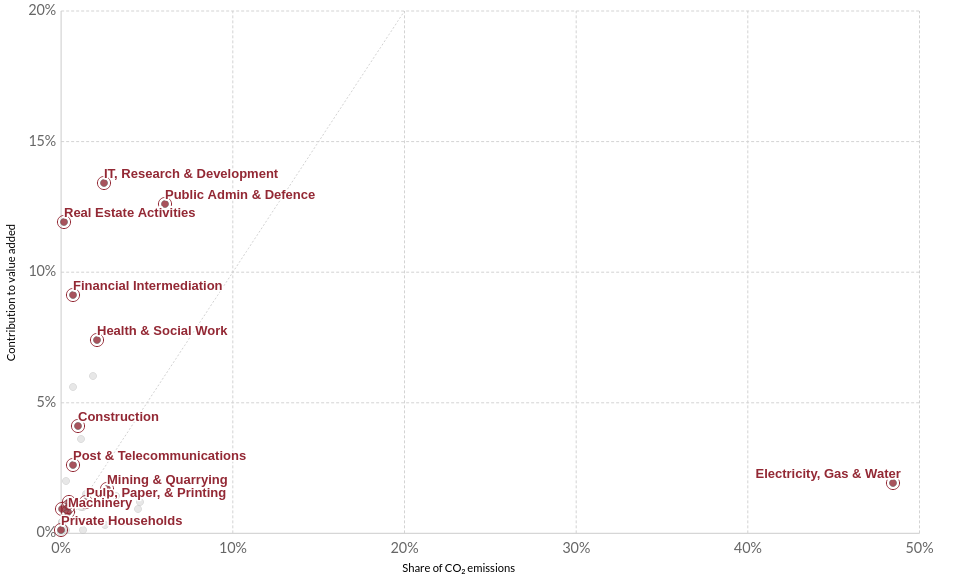

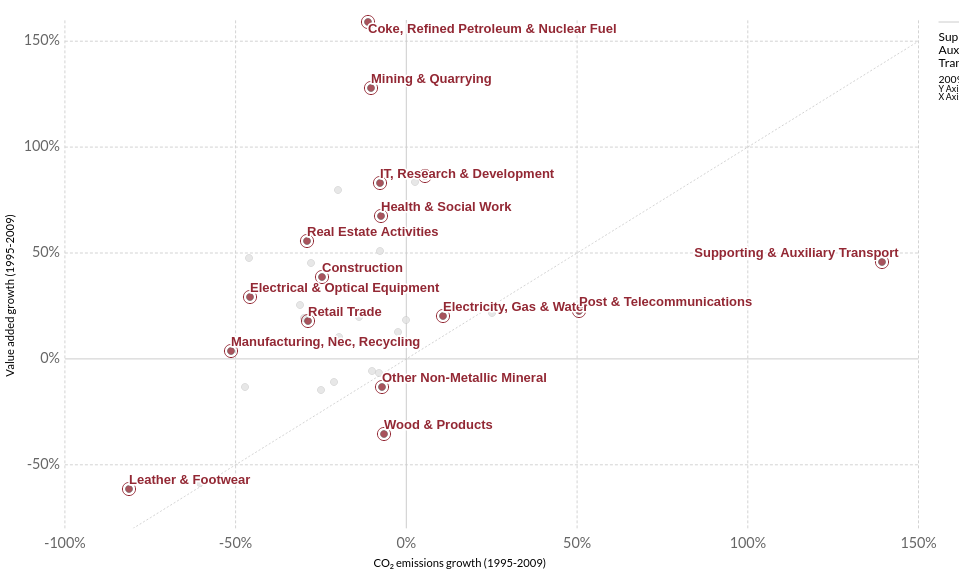

When looking at different sectors of the US economy we can compare the value they add with the CO2 emissions they produce.

Where some sectors like IT or real estate add much more value than they contribute to CO2 emissions. Other, especially energy-intensive sectors, like mining & quarrying or paper add more CO2 than economic value. However, clearly, the biggest outlier in this chart is the electricity, gas & water sector which contributes massively to CO2 emissions but creates comparatively little value.

We can also investigate how value added and emissions changed over the years between 1995 and 2009.

Where we see that some industries declined in value such as leather & footwear or wood & products while most sectors grew in value. However, the majority of sectors are in the positive-value-negative-emissions sector, i.e. they managed to grow in value but reduce their CO2 emissions in absolute terms. These are the first signs of absolute decoupling in the real world.

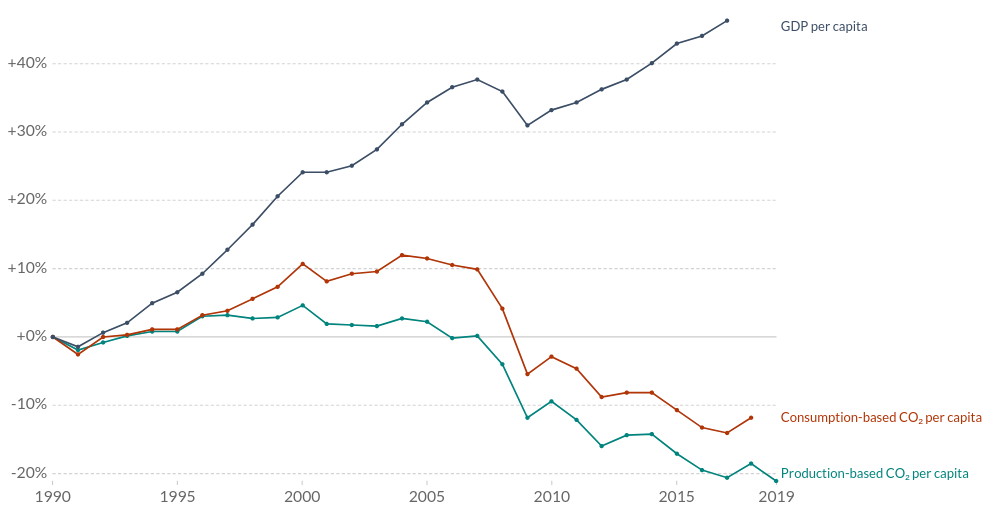

One might argue that the reduction in CO2 is only due to the outsourcing of energy-intensive industries to less developed parts of the world. And this is true to some extent (hence the gap between production-based and consumption-based CO2). However, even if we consider consumption-based CO2 per capita, which includes the CO2 emitted in other countries, we find that it has become negative in 2008 and declined since. GPD, in contrast, has been steadily growing the entire time.

All in all, I would argue that the USA has shown an absolute decoupling of GDP and CO2 emissions since around 2008.

Case study - the UK

Next, I want to look at the first large country (sorry Norway) that really implemented renewable energy on a large scale - the UK. One of the people who is responsible for a lot of this transition, Sir David J. C. MacKay, wrote a book about the topic. It’s called “Without hot air”, is available for free and it’s great.

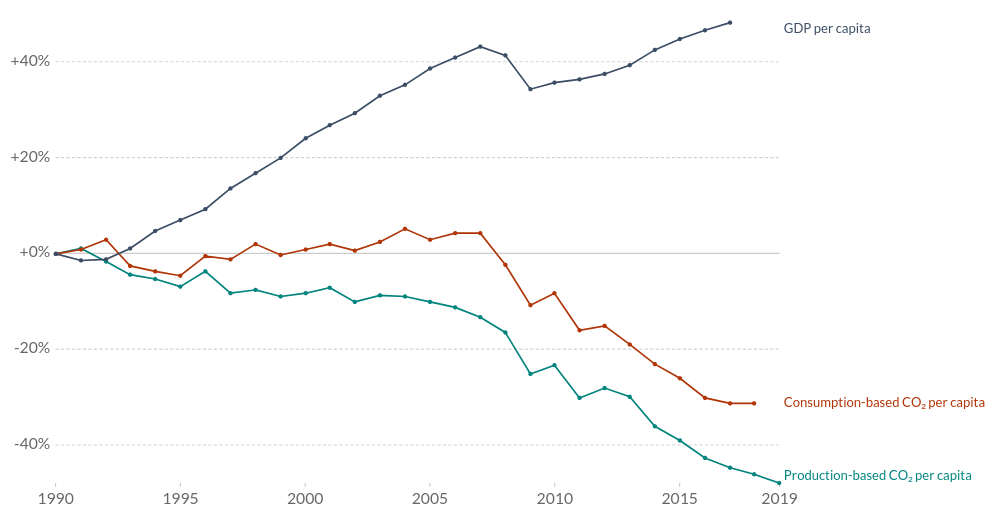

Similar to the USA, the UK’s relative consumption-based CO2 emissions have dropped below zero around 2008. In contrast to the USA, however, the UK has decreased them much faster since then.

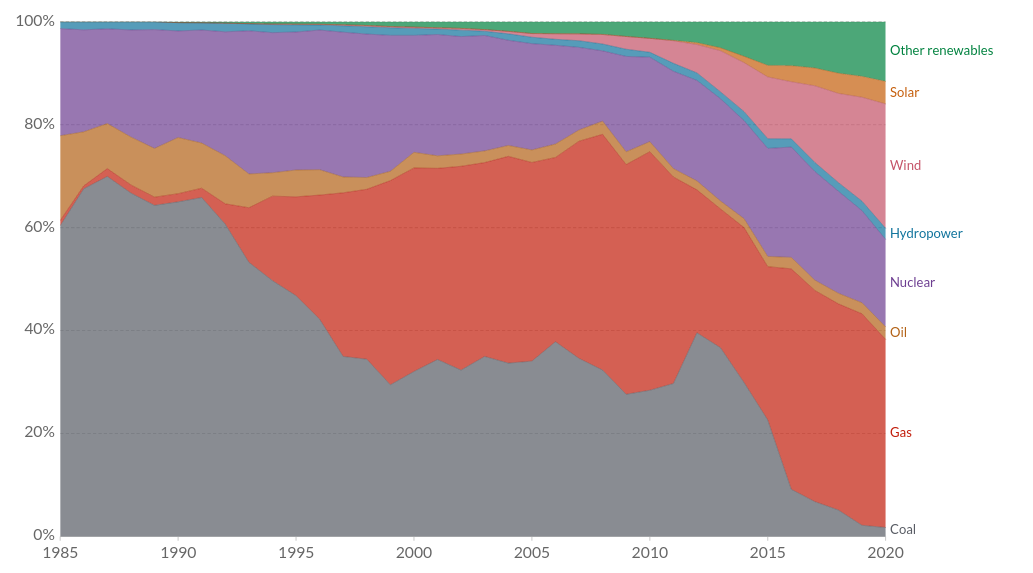

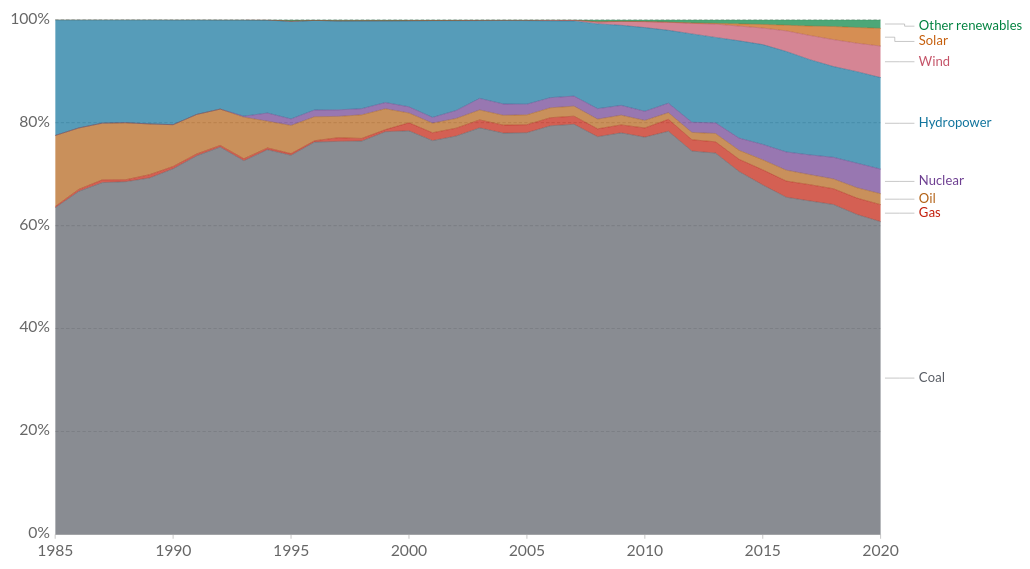

Both, when reading MacKay’s book but also when looking at the UK’s energy mix over time it becomes apparent that this is likely due to their transition from fossil fuels to renewables.

The most fascinating thing to me is that they have managed to nearly completely eliminate coal, the worst emitter.

All in all, one can see that the correlation between GPD and CO2 has become zero around 1985 and increasingly negative since then. This, I think, shows that absolute decoupling of GDP and CO2 is not only possible but can even happen quite rapidly if the political will exists and the right people are in charge of the transition. Furthermore, the UK poses a strong counter-example to the argument that an energy mix without coal would either be infeasible or unstable. Further analysis and figures can be found in this article by the UK Office for National Statistics.

The production energy mix is much more heterogeneous than I expected. Scandinavian countries produce lots of wind- and hydropower, France produces a lot of nuclear energy, Japan has switched all its nuclear energy with oil and gas after 2010 and around 60% of the energy produced in Brazil comes from hydropower. In general, I can recommend playing around with the OWID energy tools to get a better picture for different countries.

Most other developed countries’ rates of decoupling lie somewhere between the USA and the UK, i.e. an absolute decoupling is already visible even if not as strong as in the UK. However, most other countries in the world have not yet achieved absolute decoupling and in some cases not even relative decoupling. I can’t look at all of them, but I selected China since it is a very populous country with one of the most impressive trajectories of GDP growth over the last century.

Changing the energy mix is probably the cheapest solution in terms of CO2 saved per dollar invested. Other - absolutely necessary - transformations such as changing the way we build, eat and live are likely more expensive or more sticky societal problems. Thus, changing the energy sector towards more green energy is - even if already hard - is the low-hanging fruit of a transition to a sustainable future.

Case study - China

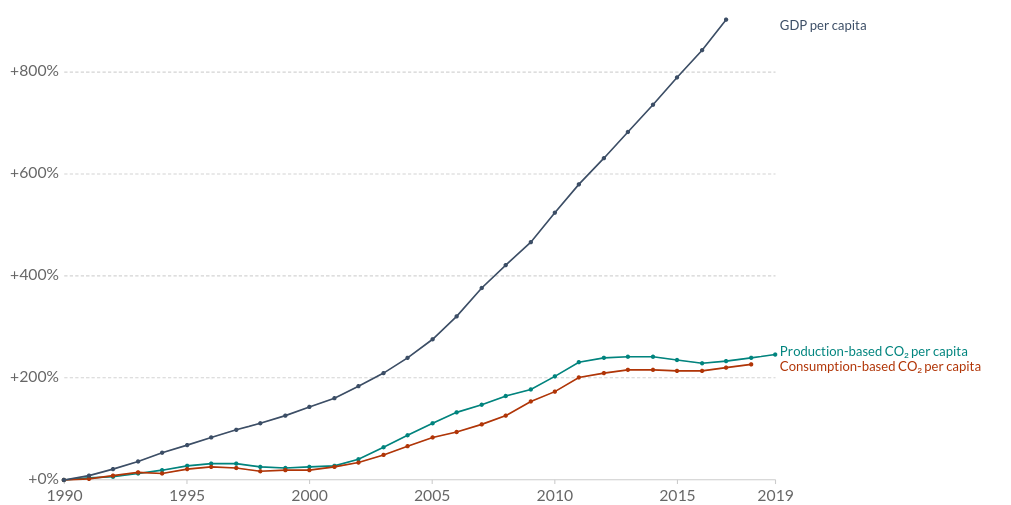

If we compare GDP growth with relative consumption-based and production-based CO2 emissions over the last 30 years we see that China shows relative decoupling, i.e. the economy grows faster than the emissions it produces.

We also see that China is a net exporter of CO2 emissions because the production-based CO2 emissions are larger than the consumption-based ones.

China’s energy mix is very fossil fuel-based, especially when compared to the UK.

A similar trend can also be seen in many other up-and-coming economies such as India, the Philippines, or Indonesia (play around with the Our World in Data tool). Since these four countries alone already have over 2.5 Billion inhabitants, solving climate change cannot be done without them.

What if we went on like this?

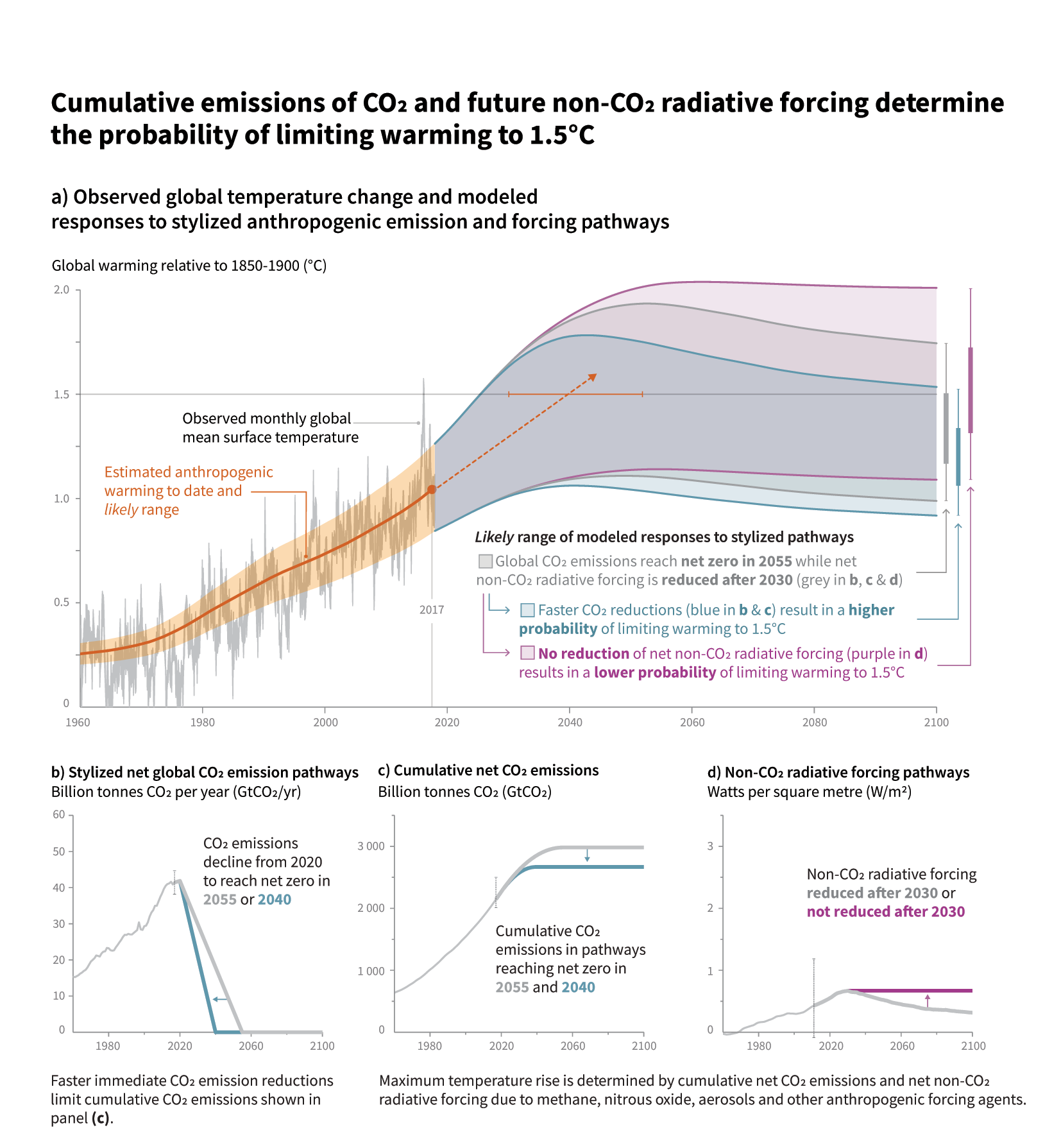

After looking at the UK and the USA one might argue that climate change will solve itself eventually. When countries become more developed they decouple economic growth from CO2 emissions and thus global emissions will start shrinking at some point. However, following the current trajectory would likely miss all relevant climate targets even if absolute CO2 emissions would eventually decline.

A meta study synthesizes 835 individual studies and concludes that “… large rapid absolute reductions of resource use and GHG [Greenhouse gases] emissions cannot be achieved through observed decoupling rates, hence decoupling needs to be complemented by sufficiency-oriented strategies and strict enforcement of absolute reduction targets”. To clarify, they explicitly state that most sufficiency-oriented strategies, i.e. strategies that only use as many resources as can be reproduced, do not require negative GDP growth.

This trajectory is captured well by the following figure from the IPCC report.

Intermediate conclusion on greenhouse gas emissions

For me, the data yield three intermediate conclusions.

- The examples of the UK, USA, and most other western countries show that not only relative but even absolute decoupling is possible. They have exhibited GDP growth while decreasing their CO2 emissions even when taking into account imported products.

- The current trajectory is not even close to sufficient. To achieve any climate target, nearly all countries have to reduce their emissions much more drastically than they currently do or plan.

- The biggest current bottleneck by far is energy production. In the value vs. emissions graph of the USA and the section on the UK, it becomes quite clear that transitions to cleaner energy are a large driver of the reduction in CO2. It is probably also the industry that is the easiest to change in terms of saved CO2 per dollar of investment.

The policy conclusions of this will be discussed later on.

What about resource use?

Sustainability is not only concerned with greenhouse gas emissions but also with resource use. The products we consume require resources such as silicon, metal, or biomass. Since most non-biomass resources are finite, they can’t be used to make infinite amounts of stuff. Either they are used up at some point like fossil fuels or they can be recycled and reused but they are always limited.

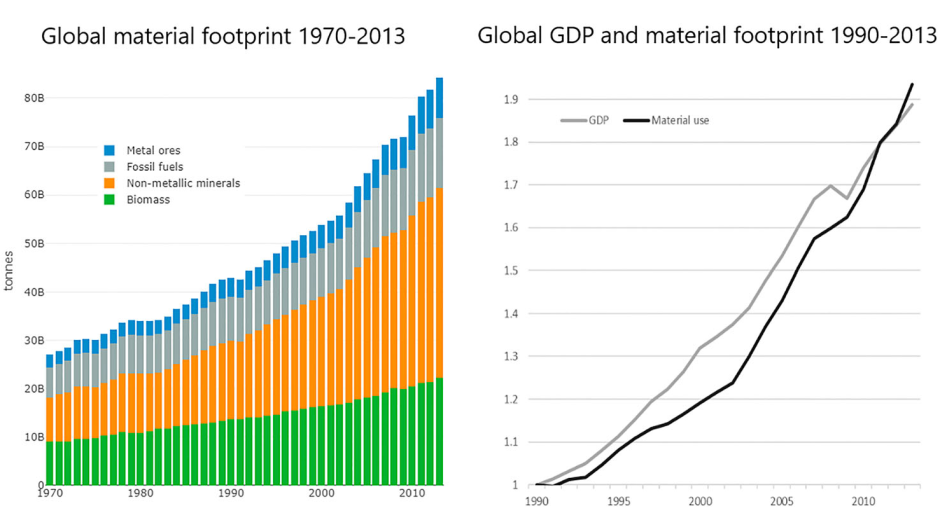

On a global scale, resource use and economic growth correlate nearly perfectly and there are no signs of decoupling.

Furthermore, the use of non-metallic minerals (e.g. sand, gravel, limestone, clay, …) is the fastest-growing sector. Since this is a mostly non-renewable resource, it cannot be exploited indefinitely and we will see shortages as we already see in sand for cement. For a fully sustainable world, the biomass sector would have to take on the majority of resource use, e.g. by replacing cement with wood as the primary material for building houses.

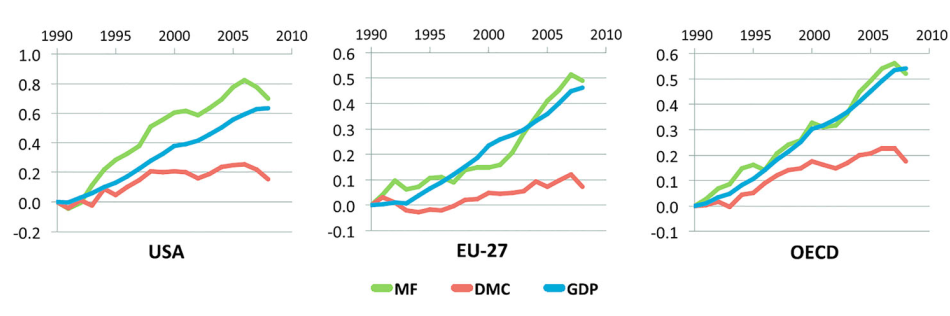

In contrast to CO2 emissions - where we saw signs of absolute decoupling in developed countries - resource use has never seen absolute decoupling.

MF stands for material footprint, which traces all resources used for a product, and DMC for domestic material consumption, which only accounts for resources used in the country of consumption. While developed countries see relative decoupling w.r.t DMC, there are no signs of decoupling for MF until 2008. This is mostly a result of increased outsourcing of production to developed countries. If we look at the years after 2008 for the USA and after 1990 for Germany, we find that a relative decoupling of raw material use (RMC) has happened, i.e. that RMC is constant while GDP is growing.

Overall this implies that to produce goods we need resources and since the majority of resources we currently use are finite, we are not on a sustainable path. Possible mitigation strategies for this problem include improved recycling strategies for important materials and the increased use of renewable materials such as wood. However, I think it is clear that if we don’t see an absolute decoupling of economic growth and resource use, the economy cannot grow infinitely since resources are ultimately finite even if we find clever strategies to reuse them.

The figures come from Is green growth possible? by Jason Hickel and Giorgis Kallis. If you want to play around with resource use data, I can recommend materialflows.net.

One could make a separate case for land use but I think the argument is basically the same. Land is finite and we can find more efficient ways to use it. But since it is ultimately limited, the only way to ensure sustainable growth is through an absolute decoupling of economic growth and land use. A good start would be to reduce meat consumption as it is much less land efficient than a vegetarian or vegan diet.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any figures that show resource use for different sectors. My assumption would be that the service sector for example would use fewer resources per GDP than the industrial sector. A friend pointed out that it might not be possible to meaningfully distinguish between the sectors as all services require resources along their chain of value generation. Your mechanic needs tools and a vehicle for transport and online services need computers or servers that require silicon, plastic, metals and so forth. My intuition would still be that there are large differences between sectors and products wrt resource use per GDP. A vegetarian diet for example is much more resource-efficient than one including meat but I don’t think it generates much less GDP. An argument against this hypothesis would be that in most countries the service sector has grown quite drastically in terms of workforce and GDP while resource use has not been reduced at a similar rate. Overall, I would need better data and analysis to have a strong opinion on whether absolute decoupling of economic growth and resource use is possible.

Economic growth is really good

Before we dive into arguments and counterarguments, I quickly want to clarify what I mean when I use the term economic growth.

“Gross domestic product (GDP) is the total monetary or market value of all the finished goods and services produced within a country’s borders in a specific time period.” (see here for more). I think the important part of this definition is that GDP is just some approximation of how much people value the goods in an economy. Therefore, GDP growth is really just a description of the average value within the economy compared to the previous year.

As a consequence, a lot of things that people might not intuitively connect with “the economy” have an influence on GDP. If you buy fair trade products it contributes to GDP. If you buy second-hand products it contributes to GDP. If you buy clothes more rarely but for a higher price it also contributes to GDP. If you don’t buy anything and leave your money in your bank account, the bank will lend the money to someone who uses it for something and thus also indirectly contribute to GDP. If you donate your money to help people in Subsaharan Africa, it contributes to GDP - just in a different country. Basically, as long as you don’t withdraw large amounts of cash and burrow them, your money will somehow contribute to GDP.

On the other hand, some things that we value do not contribute to GDP such as emotional services in relationships or housework and parenting. Since they usually happen outside of the classic economy they are often invisible to GDP and politicians might thus overprioritize GDP-growing policies over those that improve this invisible economy. While this is clearly a flaw of GDP, I think GDP is still the best lower bound approximation of “things people value” that we can work with. I would be interested in approaches to include value approximations of the invisible economy in the calculation of GDP but they don’t seem to be widely used.

Now, just because you contribute to GDP, doesn’t mean that it also grows. GDP growth is given when the goods in an economy are valued higher than in the previous year. This, however, doesn’t dictate the way in which this value is generated. Fast fashion, for example, is a resource-intensive way to generate economic growth by making and selling a lot of cheap clothing items. The same growth, however, could be generated by buying 5 times fewer clothes for the 5-fold price. It could also be generated by buying 10 times fewer clothes for the 5-fold price and using the spare money to buy something similarly valued.

What I mainly want to emphasize with this clarification is that economic growth does not require a particular way of production such as fast fashion. It merely requires that the value of goods and services increases. And as long as people make production chains more efficient, increase access to goods and services and keep up technological innovation, the economy is growing, even if production chains were more sustainable.

Economic growth is a positive-sum game

The key reason why economic growth is great is that it can be and has been a positive-sum game. This means, that everyone can get richer without making someone else poorer. Therefore, your slice of the pie can decrease in relative size while increasing in absolute size - even after controlling for purchasing power. In simpler terms, your income rises faster than the cost of the products you want to buy.

This might be a bit unintuitive in the beginning, so I want to explain it via an analogy. Assume you have an isolated community that survives through subsistence farming. They have a couple of farmers, some builders, some bakers, etc. One day, one of the farmers has the idea to use horses to speed up the plowing and invents a mechanism to increase the speed of seed distribution. Now, fewer farmers are necessary to make the same amount of goods, and thus some of the farmers are freed to work on other things. One of the builders realizes that building with stone, clay, and wood allows for bigger and better insulated houses than just using wood. With the additional knowledge and free workforce, they start to build bigger and better houses for everyone in the community. The baker invents the watermill, the weaver invents the weaving loom, etc. Fast forward a couple of years and everyone in the community has a big house, better clothes, cheaper bread, and cheaper food. They have all become richer without the necessity to exploit someone for it. Their slice has the same relative size but the entire pie is much bigger.

This is the world economy in a nutshell. Economic growth makes everyone richer in real terms if the profit of that growth is distributed somewhat equally. I know that this is not the case in the status quo, but the problem is not with economic growth but with its distribution.

In the following, I want to look at some selected statistics on economic growth that show why I think it is so important. It is basically a short version of Max Roser’s Our World in Data post on economic growth.

Firstly, let’s take a look at the growth of different countries.

We can see that most countries’ economies grow over time but we also observe outliers such as Zimbabwe. We can investigate this in more detail for all countries in the world by comparing their GDP from 1950 to 2016.

We find that some countries’ GDP declined while most countries’ GDP increased. On average the GDP increased by a factor of 4.4.

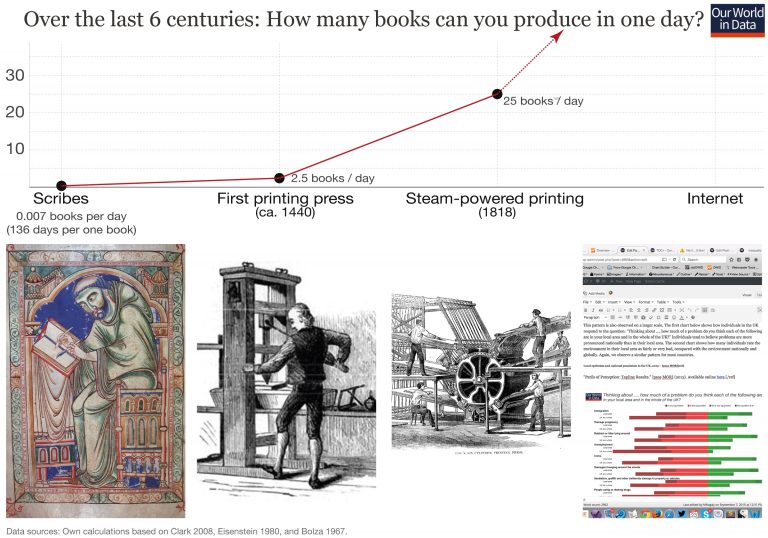

One example that gives insight into where this economic growth might have come from is the efficiency gain in the production of books. Before the invention of the printing press, it took 136 days to produce one book and with the internet, millions of books are created and distributed every minute.

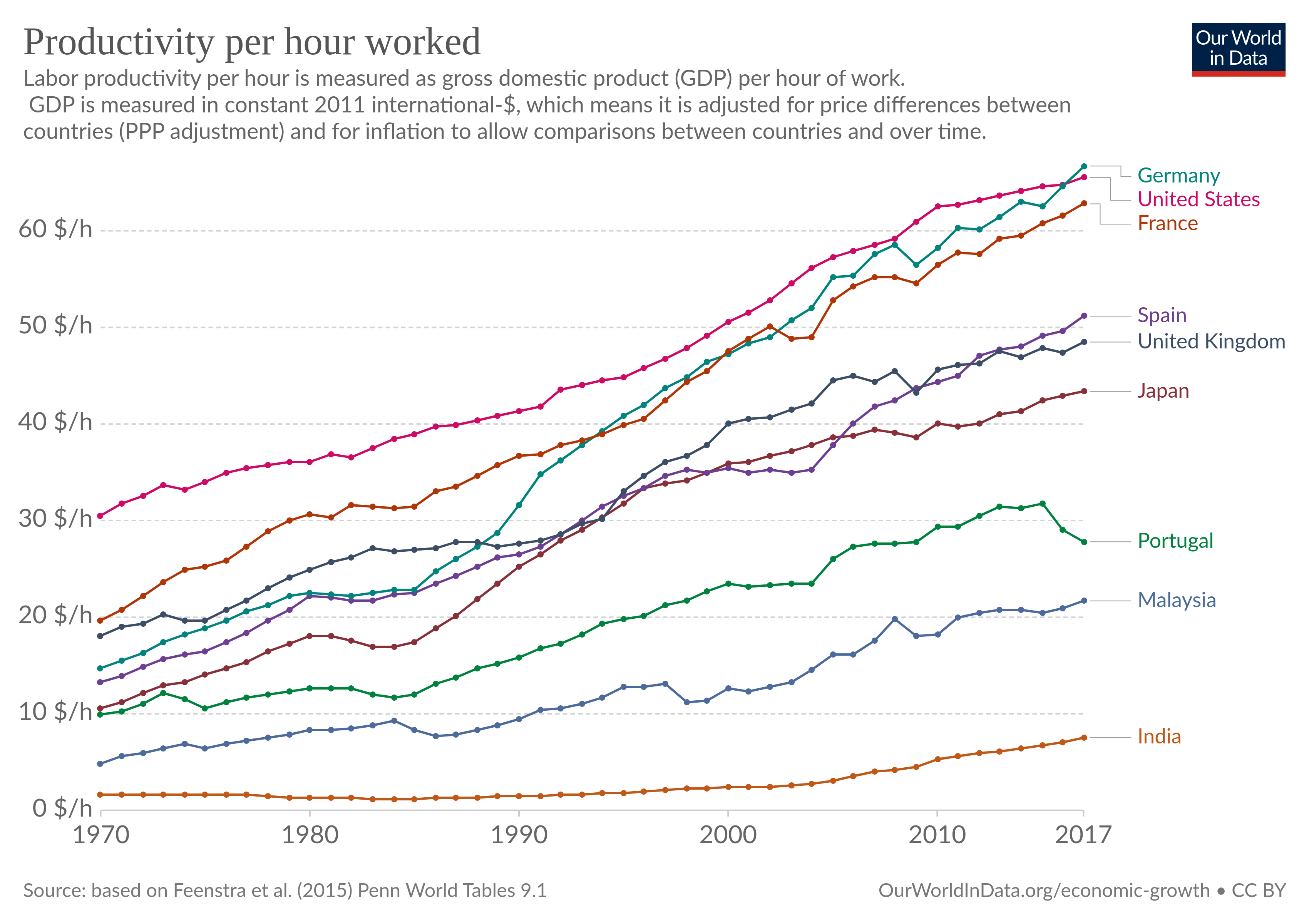

Obviously, this kind of productivity increase is not given in all sectors but most countries at least tripled their average productivity over the last 70 years.

Now lastly, I want to show one of my favorite charts of all time - the decrease of absolute poverty.

While in 1820 90% of the population lived in absolute poverty, today it is only 10%. Importantly, these numbers are based on 1.90$-international, which accounts for differences between countries and is inflation purchasing power adjusted, e.g. the poverty threshold for someone living in Germany would be much higher than in Senegal and these numbers account for the change in prices between, let’s say 1950 and 2000.

For me, this is the main reason why I like economic growth - it makes poor people richer and thereby increases their quality of life, life expectancy, and freedom. An average global citizen today is as rich as a king in the middle ages - even after accounting for inflation and purchasing power.

But what about …?

Obviously, economic growth doesn’t come without criticism. I think that some of them are misunderstandings of how economists measure economic growth and I want to address them first. However, I would say there are definitely very problematic ways in which growth has been generated in the past and today, which I want to address as well.

Aren’t we rich enough?

Some people might argue that we are already rich enough and thus growing further is unnecessary. To this, I have three answers.

- This might be true for some very fortunate people in the West, but the vast majority of humans (>5B) doesn’t live in the West and in circumstances in which more money would mean a lot to them. It could unlock better health, better education, more individual freedom and much more. So, the vast majority of humans are not rich enough.

- The world’s economies are interlinked. Economic shocks in one region of the world propagate to others and thus stopping economic growth in some parts of the world would likely have negative ripple effects on others.

- A longterm perspective. A person living in 1900 might have thought “I have it much better than the people around 1800, maybe I’m rich enough” and thus could have argued that economic growth wasn’t necessary anymore. However, if we assume that economic growth leads to higher life expectancies, better health outcomes, and more freedom, then these will only continue to grow in the future. To the people 200 years from now we are poor peasants who only lived for 80 years and died of laughable diseases like cancer or Malaria. I want future generations to be less poor in the same way that I want current people living in absolute poverty not to be poor even if I might not live to tell the tale.

If you personally feel rich enough, you can always donate to the global poor.

If everyone is rich, nobody is rich

I think the two main counterpoints to this argument have been discussed before, namely a) economic growth is a positive-sum game and b) economists account for inflation, the difference between countries, and purchasing power when measuring absolute poverty.

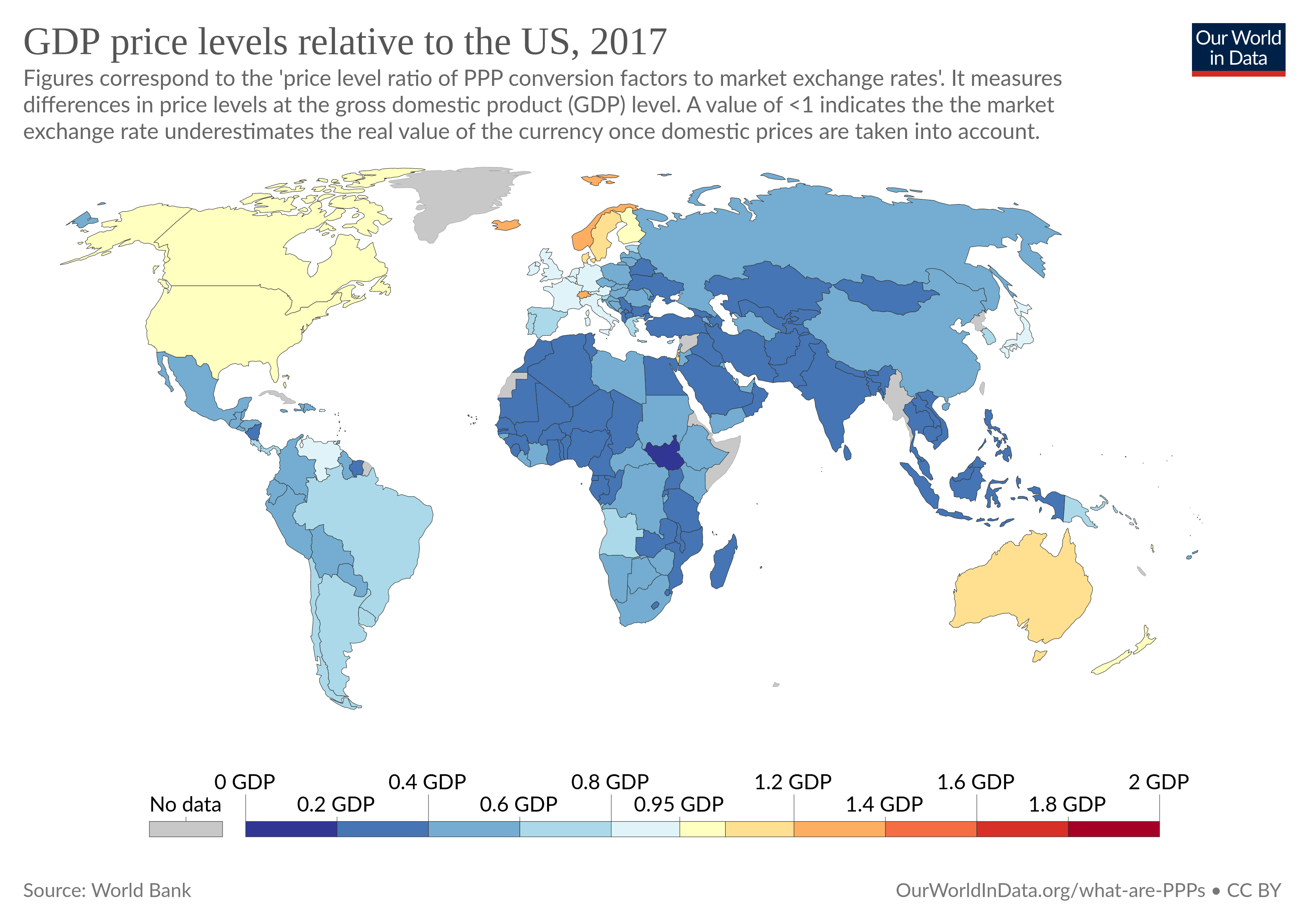

To elaborate on this, we can look at the purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates between the US and other countries in the world.

Basically, this just means that it’s cheaper to live in many other countries than the US and the economists have a way to account for it and do so when computing absolute poverty.

The ugly parts of growth

There are a lot of ugly parts to the world economy. They include

- Massive wealth inequality: This thread on the annual Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report 2021 summarizes some of the most important facts of inequality. For example, “the average wealth per adult in the wealthiest continent (N. America) is 66x that of the poorest (Africa)” and “Only 1.1% of world adults have wealth above a million dollars. This one-percenter group accounts for 45.8% of total world wealth. The bottom half (55%) of the world adult population account for only 1.3% of total wealth.” I don’t think a uniform distribution of wealth is optimal but this kind of inequality seems too inequal to me.

- Exploitation and forced labor: Many people in this world have to work for a very low wage, under poor health conditions, and for long working hours.

- Pollution of the environment: See the first part of this post.

These are clearly very bad and we should try to improve them. However, it is important to note, that they are not necessary for economic growth to happen. Economic growth does not require the exploitation of workers, it does not require massive wealth inequalities - it merely requires that the people value available goods and services more than in the previous year and they are willing to pay for them.

Just because I like the benefits of economic growth, I don’t have to defend or support everything that has ever lead to it such as colonialism or slavery. We can and should try to change the ways in which economic growth is generated in the same way that we fix other systems that are currently suboptimal but overall very beneficial such as science or education.

Alternative systems

It is sometimes argued that the problem of climate change is inherent to capitalism and thus a system change is necessary since capitalism requires economic growth. In the previous section, I tried to argue why those problems are not endemic to economic growth or capitalism. In this section, I want to investigate alternative systems and whether they are likely to solve the problem of climate change or resource use.

Degrowth

The degrowth movement is rather young and thus a clear definition has not yet been established. Therefore, I have come across different framings of degrowth which I will categorize into strong and soft degrowth.

Strong degrowth

The first is what I will call strong degrowth. I will use the goals and strategies that degrowth.org states on their website and in the accompanying video as a working definition for strong degrowth.

I’ll try to steelman their argument as much as possible, but I have to say that I found some of their argumentation quite frustrating. In the video, for example, they claim that the growth of GDP has not benefitted the poor over the last 10 years. To support this claim they cite that the net worth of the poorest 20% of Americans has stayed constant since 2008 while the top 5% have accumulated massive gains. And while this is true in the USA and financial inequality is a massive problem, hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of absolute poverty in the same timespan around the globe. There are other claims that I find similarly deceptive, but let’s not get lost in the details and look at their main theory.

Strong degrowthers argue that economic growth is always linked to more climate change since people buy more stuff when they get richer and the production of this stuff creates pollution. As an alternative, they want to reduce growth or even create negative growth by making production chains less efficient, reduce working hours and thus implicitly raise prices such that consumers buy less. Furthermore, they argue that the wealth that Western nations currently have could be redistributed globally through global democratic institutions and thus economic growth is not necessary to lift developing countries out of poverty.

I definitely agree that there is a massive global inequality of wealth and would be in favor of these democratic redistribution organizations. However, I’m not sure where the political capital for them would come from, especially because it would imply that Western citizens would be much poorer as a consequence and thus likely lobby against them. If there is a theory of change for these institutions, I might be persuaded, but it has not been provided yet. I think massive investments into green energy are more likely to find political capital because they great growth, jobs and wealth rather than redistribute it.

Ultimately though, I’m not convinced of the fundamental premise of the strong degrowth movement, namely that economic growth is always linked to climate change and green growth is impossible. The only argument that the website makes is that this has historically been the case. However, they do not engage with the countries in which absolute decoupling has already started, with a transition to service economies or basically any argument for the possibility of green growth. If someone can explain to me why this link necessarily exists or can’t be untethered fast enough, I might be persuaded. Until then, I find the arguments and data for the possibility of green growth more persuasive.

Another thing that I do not yet understand is how the strong degrowth movement plans to actually create degrowth. Ultimately, to create localized self-sufficient economies you have to stop or massively reduce global trade, e.g. through large tariffs. This will, with high probability, impact people in growing export-oriented economies such as South East Asia the hardest and keep them in poverty. Since I find it implausible that we can redistribute existing wealth at the scale that would be necessary, reducing economic growth through tariffs probably just makes poor people even poorer.

Soft degrowth

The second approach I will call soft degrowth. I’m not sure if there is one particular resource that provides a concise summary but the book Prosperity without Growth or The Doughnut economic model might be good starting points.

An economy can be optimized for a lot of different metrics. While economic growth is one of them, there are many others such as social cohesion, climate change, pollution, etc. In simplified terms, soft degrowth argues that we currently overoptimize for economic growth while neglecting all the other components. Thus, soft degrowth proposes a reweighing of the different metrics which would deprioritize economic growth. Importantly, they don’t argue that economic growth is bad, just that it’s not imperative and should not be forced at all costs.

As a consequence, soft degrowth would argue that the ways in which we currently allow companies to extract resources or pollute the environment for the sake of creating economic growth is wrong and misguided and the latter should thus get more weight in political decision-making. Therefore, it might be possible that the economy could (temporarily) shrink while we sort out the sustainability problems - thus the name soft degrowth.

Examples of policy proposals include: a) Companies being held responsible for human rights violations down their production chain. This would weigh another metric, human rights, higher than economic growth and might implicitly lead to a reduction of global GDP. b) Laws that force companies to produce a common good balance sheet, where they have to make public how much they emit and provide certain social information about e.g. their employees. Companies that score high for common good would be subsidized and low scorers would be punished. c) An economy that is built on True Cost Accounting where all external costs are internalized. This is similar to CO2 taxes but for many more aspects such as resource use, land use and potentially social aspects such as future health costs of exploited workers.

I think all of these sound like pretty good ideas. But it is hard to accurately approximate these costs and then implement a system that is hard to game for individual companies. In any case, economic growth would probably at least temporarily drop as a consequence since many current products are built on unsustainable practices. If I were to build such a system, I would slowly start to internalize more and more externalizable costs and hope that market forces react to the change and create economic growth while becoming more sustainable in the meantime.

I think one could come to similar conclusions with a longterm perspective on economic growth, e.g. to ensure growth in the future, we can’t exploit the planet for fast gains in the present. But overall, I’m sympathetic to many ideas of soft degrowth. The most important distinction between strong and soft degrowth - and why I prefer the latter - is because it acknowledges that economic growth has a lot of benefits and is not in itself bad.

Communism

Capitalism and Communism are distinct concepts from economic growth, e.g. there can be economic growth within a Communist system. Thus, I personally think arguments along the lines of “Communism would be a solution to climate change because it doesn’t require economic growth” are based on a misunderstanding of the terms. However, the argument is made so often in public discourse, that I feel like I should address it anyway.

When people suggest communism as an alternative to solve climate change they can mean very different things.

Firstly, they could mean a social democratic system like Norway and mislabel that as communism. Norway is a country with a better social system and cleaner energy mix than most other countries in the world. However, its economic system is very clearly capitalist. The market decides what supply and demand is for the vast majority of goods and not a government planner. So when people mean “the world should be more like Norway”, I’m happy to support them but they then are not embracing communism as a system.

Secondly, communism is sometimes used to describe a certain culture or vibe which can include sharing culture, the use of second-hand goods, or demand for fair-trade products. While I’m happy for these people and share this vibe/desire to some extent, it is just not clear why communism would improve it in any way. Within a capitalist system, your desire is translated into demand and someone will provide fair-trade products, found a sharing cycle, or program an online platform for second-hand goods and thereby also contribute to GDP. In a communist society, you have to hope that the people in power actually consider this a problem and target it in their next 5-year planning cycle. I’m not sure why this is more likely to happen than when you create the demand yourself.

Lastly, people might argue that the actual economic system of centrally planned economies often found under communist regimes might be a better fit to solve climate change than a mostly free market under capitalism. While I understand the initial intuition of “If we care more about each other, we might actually do something against the climate together”, I think a lot more arguments speak against communism as a solution.

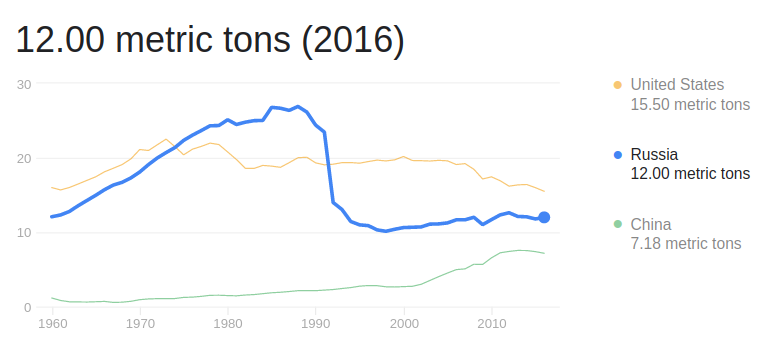

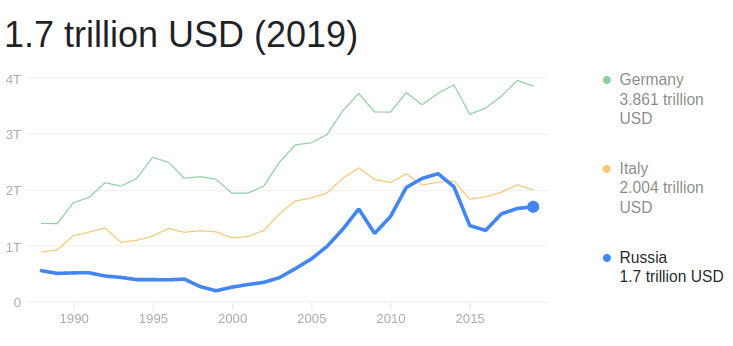

First of all, the biggest communist system that we have had so far, the USSR, was much worse for the climate than its capitalist competitor and replacement.

The CO2 emissions of Russia decreased 2.5-fold after the collapse of the soviet union while GDP was basically not hit at all. Of course, you could argue that the USSR was just a particularly bad implementation of communism and that a better implementation might solve climate change nonetheless. However, I think communism is systematically less probable to solve climate change than capitalism.

In communism, a company has to meet a certain production target. There is little or no reason to improve the efficiency of production as long as the target can be met. Thus it doesn’t matter whether you use coal or wind to power your grid, as long as the energy target is met. If the state gave CO2 targets to combat climate change, there would be no reason to undercut it as you don’t reap the profits.

In capitalism, on the other hand, there is always competition for lower prices and thus an incentive to increase the efficiency of production. This means that people are interested in decreasing the energy cost of action because it will improve their profit margins. This, of course, is not a defense of the status quo. Currently, companies have very little incentive to care about climate change because the cost is externalized to future generations. Thus, the key challenge for climate change within a capitalist system is to price these future costs in and align the incentives of companies with those of the broader population.

Policy implications

After looking at the research and data, I come to the following implications for policymakers.

-

Massive investments into green energy are necessary: As shown in the first part of this post, the rate of decoupling is very proportional to the amount of green energy within a country. When green energy transition is too slow, countries should try to replace coal with gas and nuclear energy since coal is a much worse emitter. Since the clock is ticking, these investments should be massive and much larger than all countries are currently planning. They should be at least as ambitious as the green new deal proposed by AOC, i.e. in the hundreds of billions of dollars. They are probably not only net positive for the environment but also for the economy. They create new jobs in the renewable energy sector and large infrastructure investments such as public transit unlock economic potential by freeing poor people from the necessity to own a car.

-

CO2 taxes and emission trading: The largest reason why the current economy doesn’t reduce CO2 emissions on its own is that the harms are not priced in. The costs are externalized and it is thus rational to emit CO2 whenever it is profit-maximizing. Therefore, countries have to implement schemes that price in these harms such as CO2 taxes or emission trading schemes. An argument that is often made against the pricing of CO2 is that companies would not be profitable anymore or leave the country. While I think this is certainly a realistic argument it is strongly mitigated by the fact that there are a lot of innovative eco-friendly companies who are not yet profitable because others get a free pass on pollution. I’m not sure which of these two is stronger, but I think this argument could be used more in the political discourse on climate change to get rid of the “economy vs. environment” fallacy.

-

Things that don’t make sense: I don’t think reducing global GDP, e.g. through the introduction of trade barriers, helps. If the cost of CO2 was priced in, the largest possible market would lead to the least emissions. Larger markets mean more competitors and more access to consumers which leads to more efficient chains of production. If someone is able to produce a good on the other side of the world and ship them to you while having lower emissions and prices, then this is a good thing.

Conclusions

- Climate change is bad and current trajectories don’t come close to a solution: Even though some economies transition to renewable energy and the service sector increases in most countries, the current trajectory is not even close to meeting any relevant climate target.

- Economic growth is really good: It has reduced absolute global poverty from 90% to 10% of the world’s population over the last 150 years. These numbers account for inflation, differences in countries, and purchasing power parity. Thus, it is fair to say that the average person today is much richer than a high upper-class person (e.g. top 5%) 100 years ago.

- It seems possible to decouple economic growth from CO2 emissions: Many Western countries already see absolute decoupling, This will likely happen through a transition to green energy and away from production-heavy industries to e.g. service economies. Up-and-coming nations such as China already see a relative decoupling. However, since the majority of people live in less developed countries, solving climate change is very dependent on the speed of their transition to clean energy.

- Resource use has never been absolutely decoupled from economic growth: The use of resources such as rare earth, metals, sand, cement, etc. has historically not been absolutely decoupled in any country. Some developed countries such as the USA or Germany have seen relative decoupling.

- Massive investments into green energy and pricing schemes for CO2 are necessary: These strategies can include CO2 taxation or emission trading. Given that the time is ticking, the investments should be very large, i.e. in the hundreds of billions of dollars. These investments would likely also boost the economy and thus partly pay for themselves.

- Alternative systems such as degrowth provide important insights: From my understanding there are different conceptions of degrowth. There is strong degrowth, which argues that only decreasing global GDP can stop climate change. They leave too many important questions unanswered and I thus don’t give them much credence. Then there is soft degrowth, which argues that an economy is always maximized for multiple metrics and currently we drastically overvalue economic growth over, e.g. reducing resource use, pollution or social inequality. I find this very convincing because it accepts that economic growth is good and merely argues that it has to be one of many considerations instead of the only one.

One last note

I would like to thank Mona, Maria, Eric and Emil for their in-depth feedback

If you want to get informed about new posts you can follow me on Twitter or subscribe to my mailing list.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.