what is this post about?

I recently had a conversation with one of my best friends about her Aphantasia. In short, she can’t create mental images. When she thinks about the world, she thinks in text, relationships, sounds, and much more but never images. Even if she tries, it’s impossible for her. I found this experience very revealing because it showed how much I expected everyone else to experience the world in basically the same way that I do.

After this revelation, I talked to a bunch of people about how they viewed the world. Not about their specific beliefs and opinions but rather in what way they think. And I found that the differences in how people think are much bigger than I expected.

For example, when I think about “Traveling from Tübingen (where I currently live) to Nuremberg (where I grew up)”, I make the journey in my head. I “fly”/zoom from my home to the train station, zoom through all the intermediate train stops in my mental model, get out and zoom to my parent’s house. Of course, I don’t have a perfect model of the intermediate steps but it’s sufficiently good to fly around. Not everyone I talked to, does that. For some, it’s just a one-step thing. They start in Tübingen, and then they teleport to their hometown in their head.

For music, on the other hand, most people have clear associations in their heads. When they listen to music, they see colors or flows, they feel the melody with different emotional states, they feel an urge to move to the rhythm, and much more. In any case, most people seem to have clear associations with music even if they differ from person to person. I mostly don’t. I don’t really see anything, I don’t feel that much, and I don’t really have an urge to move.

For the rest of this post, I will refer to the concepts shown in the examples above as mental building blocks. What I roughly mean is “a way to think about a specific concept” or “looking through a specific lens” or “a tool in your mental toolbox”. However, I find it very hard to define more properly and I don’t claim that the thing I mean is actually consistent. Feel free to point out flaws or suggest improvements.

Importantly, mental building blocks are not fully static, e.g. I expect that people can get better at mental models of locations or understanding music. However, some people find it much easier and much more natural to fly around in their mental world model or to associate things with music to begin with.

In the rest of this post, I want to try and explain in more detail why I think these building blocks are more different than I expected and why it matters.

I’m not an expert in any of this and there are probably much more serious people who thought about these questions for much longer. You should see this post as food for thought and not as rigorous research.

Sports as an analogy

For sports, it’s very obvious that different people have different physical building blocks. It’s obvious that someone who isn’t tall will have a much harder time playing basketball than someone who is. It’s obvious that people with lots of slow-twitch muscle fibers are better at long-distance running than those with lots of fast-twitch muscles. It’s clear that some body types are better for climbing, swimming, cycling and so on.

It’s also clear to us that there is a component to these physical building blocks that we don’t have any control over. I, for example, could become a decent basketball player if I trained hard, but I would never be able to play in the NBA (and probably not in the next 5 divisions either) because my physical building blocks don’t favor it. I’m 176cm tall and weigh 62kg while most basketball players are more than 200cm tall and weigh more than 110kg. They are quite literally built different.

My claim is now that the differences in mental building blocks are comparable to differences in physical building blocks even if they are much less visible. I’m not sure if they are similar in magnitude but they could be.

One thing that I expect to be transferable between physical and mental building blocks is that most people usually don’t notice these large individual differences. For example, when you ask a very talented tennis player how they play tennis that well, they don’t have a precise recipe to replicate their outcomes. For them, it’s completely obvious what to do. In their head, they “just do the thing” and they are confused that everyone else isn’t “just doing the thing”. I think this is a common trend among people who are naturally very good at something. Rather than being convinced that they are really good, they are perpetually confused that everyone else is so bad.

How are our mental building blocks different?

Lots of examples

Here are lots of examples, to pump the intuition. All people I talked to were roughly as old as I am, so age is not a major confounder.

- Mental models of locations: Think about the high school you went to. Do you have a mental model of the building? Could you run/fly/zoom through the entire building in your head? How detailed is your model? Could you open a door and look into the room? Can you count the number of chairs as they are or just count the number of chairs of a “plausible classroom”? When I played this game with different people, most could create a rough model of their school. However, the level of detail varied quite heavily. Some could count the chairs, others could just fly through the halls and others didn’t even quite remember how many floors the building had.

- Music: As I said in the intro, I don’t really “feel” music. I don’t have strong associations with it, it doesn’t make me want to move, I don’t see colors or flows or anything like that in my mind and I only realized quite late that most people are not like me. Until I was maybe 16 or so, I mostly thought that music is 100% signaling. I thought that you sing, dance and compose because you want to impress someone else. I just couldn’t imagine that anyone would do music-related things because they intrinsically enjoyed them. I did play the guitar for multiple years but always only because I wanted to impress someone, never because I enjoyed it. By now, I expect I have some form of musical anhedonia.

- Social interactions: I think it’s clear that some people are “just better” at social interactions than others. However, I never really understood this in detail. For example, I recently learned that some people have a hard time noticing when others are flirting with them. And while there is obviously always some uncertainty when it comes to flirting, I usually felt like I know when people flirt with me and when they don’t. I couldn’t write a classifier that distinguishes between flirting and not flirting or explain the exact nuances but I feel like “it’s just obvious” (I haven’t actually collected data on this, so this is just my intuition).

On the other hand, I have a hard time reading most situations that involve courtesy. Do people expect me to shake their hand? Do they expect me to hug them? Do they expect me to help with the dishes or would I just create chaos in their kitchen order? Should I keep my shoes on or off? In these situations, I’m just mostly confused and think “please just talk to me” in the same way that the people who have a hard time reading flirting might just want to be told if the other person is flirting with them or not. - Range of emotions: I have a very low variance in my emotions. Most of the time I’m just “normal”. I’m basically never angry, I’m sometimes a bit sad, I’m sometimes happy but rarely ecstatic, … you get the gist. Most other people I talked to experienced much larger ranges both towards the upper and the lower end of the spectrum. From the way people behave, I guess it was always obvious that most people experienced more extreme emotions than I do but it was still interesting to try to understand how it feels inside. For example, I very rarely (if at all) felt so angry, that I couldn’t control myself while many other people have said that this did happen to them from time to time. Unfortunately, the same is also true for extreme happiness. I’m very rarely so happy that I can forget everything else around me and just enjoy the experience.

- Baseline happiness: Like I said above, most of the time, I’m somewhere between “just fine” or “mildly happy”. I’m neither very sad nor very happy. Some other people I met said their baseline state was very happy and others said their baseline was pretty depressed. Just understanding this was very insightful. For example, some behaviors that I previously didn’t understand suddenly made sense. One person that I previously thought of as “careless” just had a high baseline happiness and therefore some things that would make me unhappy just didn’t bother them enough to do anything about it.

- Sense of orientation: I always had a very good sense of orientation. I never really learned it, I never actively trained it–it was just always there. I usually have no problems navigating a map, I usually know whether I’m going south, west, north or east without actively trying. I’m usually able to navigate a route if I took it once, even if it’s a year later or in the other direction. Apparently, most people can’t do that and for the longest time I thought “they just weren’t really trying”. Only when I noticed that they are really trying, I realized that we just had different mental building blocks to work with. Unfortunately, this skill is not very useful since Google Maps exists.

- Feeling like an imposter: Sometimes you feel like you don’t belong in a group. Everyone else feels much smarter, it’s like you have been placed there by accident and you can’t really contribute. I guess most people have felt that to different degrees but I still find it interesting how large the variance is. For example, I have seen people who were probably really underqualified who didn’t feel like an imposter and others who were likely the most qualified person in the room and still intensely felt like an imposter.

- Imagining pain: Think about how a bee stings your arm. Think about stepping on a lego brick while barefoot. Think about hitting your toe. How does it feel? In my head, it’s like “that would be bad” but I can’t simulate the experience at all. Other people have reported that they can really simulate this experience in a more or less realistic way. When they imagine the bee sting, they can really “feel” it.

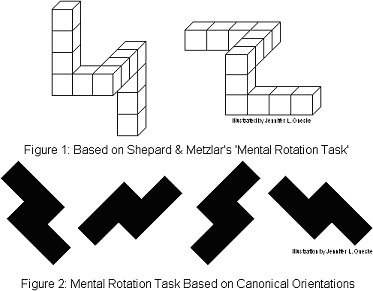

- Rotating shapes: Are the shapes below the same? Can you rotate them in your head effortlessly? Some people can and others can’t. I guess the shapes below are sufficiently easy for everyone to rotate but some will need much more effort than others. The specific ability to rotate shapes in your head is not that important but it is often seen as a predictor for STEM-type skills. I haven’t read the scientific literature on it and don’t know about its effect sizes though.

- Generating words: I find it hard to generate words. I think my vocabulary is quite small compared to other people, I have a hard time finding synonyms or finding words that rhyme. Other people I know are much better at that. For every word I can come up with, they can immediately generate a synonym, antonym or a word that rhymes even though they never actively trained that skill. One of my best friends was already insanely good at this when we went to Kindergarten together, so it seems plausible to me that his mental building blog for “language-related things” is just built different.

- Levels of empathy: When I watch a fail compilation I actively flinch when people hurt themselves, I want to look away and it’s a mostly bad experience. Other people don’t have this at all. They can laugh about it and don’t feel for the people in the compilation. Interestingly, I could also laugh about this stuff when I was 12 but it’s now impossible.

- Scared of heights/stage fright: Some people are scared of heights and some aren’t. Some people have stage fright, some don’t. The thing that I mostly want to point out here is that it feels real from the insight, no matter how justified. I can tell myself that I’m safe a hundred times, but I still feel a bit weird when looking down from high places.

- Risk Aversion: Some people tend to be much more risk-taking and others much more risk-averse. Interestingly, two people can agree on the risk that an action has and on the value that action has and still have very different intuitive judgments. With the same expected value, the risk-averse person still thinks “I’m unsure about this, the risk seems too high for the value” while the risk-seeking person thinks “this looks fine to me, the value seems good enough to take the risk”. I guess even when people rationally agree on the expected value, their intuition still focuses stronger on either the risk or the reward and thus biases the final judgment.

- The Autism spectrum: I guess Autism is probably the most salient example of different mental building blocks. People on the spectrum tend to have a sensory overload much faster than neurotypical people, they often find it harder to read social queues or have a preference for following plans rather than spontaneously making decisions. I think for Autism it is especially clear that “just get a hold of yourself” is not an adequate response and that different people just see and interact with the world in very different ways.

These are, of course, just a small selection of the ways in which our mental building blocks differ. The main thing I want to convey is that whatever concept you think about you should realize “Oh, most other people probably think about this in a different way”.

Nature and nurture

I think both from a perspective of nature and nurture it makes sense that our mental building blocks are about as different as our physical building blocks.

Let’s start with genetics.

- Random variations: It’s plausible that some genetic mutations affect how we think about the world. In the same way you might have a different height than your parents, one mutation might imply that you think about the world slightly or even drastically differently.

- Cumulative effects: If we assume that most genetic mutations are small, the accumulation of them could still be large. For example, even if my mother and I have very similar building blocks, you and I might still have very different ones if our distance in the family tree is large enough.

- Geographical effects: I find it vaguely plausible that some mental building blocks are more important in some regions than in others. For example, in some parts of the world, having a good sense of orientation might be more important than in others. Or people living in the desert might not evolve a fear of heights (not sure about this one). In any case, this could mean that the geographic timelines of your ancestors have an effect on how you view the world today.

There are also some plausible social explanations.

- Learning a concept: Maybe your way of viewing the world is not innate but learned. The way your parents and teachers talked about the world made you think in specific patterns. For example, maybe my sense of orientation was taught to me by my mother at a time I can’t remember or maybe my bad musical abilities come from not listening to enough music as a child. In any case, it’s plausible that nurture contributes at least some part of your mental building blocks.

- Culture: The culture in which you grow up definitely influences how you think in many ways. So it would be plausible that your mental building blocks are influenced as well. For example, I’d find it plausible that people who live in cultures where you “are not supposed to talk about emotions” have a worse understanding of other people’s emotions. Maybe the culture prevented them from developing some mental building blocks that people in other cultures acquired.

These claims are speculative and should be taken with a grain of salt since it is almost always possible to create a relationship between anything and nature+nurture. However, I find both explanations plausible enough that I would give them some contribution to “our mental building blocks are different”.

Individual differences

In many different subfields of science, there is a large and growing body of literature on individual differences. Conventionally, science tries to find aggregate effects, i.e. it tries to find whether there are universal trends among all people they examine. Individual differences describe effects that are significant for single individuals but not necessarily universal among people, e.g. some people might consistently react to a stimulus while others consistently don’t react to it. In that scenario, there is not a universal trend but there are significant and consistent individual differences.

I’m not very familiar with the literature but I think it broadly reflects a similar intuition, namely, that people can differ a lot along a specific dimension and that many effects are not universal.

This is, of course, no scientific evidence for my mental building block theory but along the lines of “there is something comparable that serious scientists think about”.

What does this imply?

Interaction

On a basic level, I think you should just assume that people think more differently from you than you expected. This has a bunch of implications.

- Assume other people’s mental building blocks are static: I have witnessed the following pattern over and over again. Person A is unable to do X, e.g. they have a hard time reading a map. Person B who is able to do X thinks or says something like “come on, it’s not hard, just do the thing” because for them reading the map is obvious and easy. Then person A struggles with X and still can’t do it while person B gets increasingly frustrated.

The problem is that Person B answers the question “What should person A do if they had my mental building blocks” and not “What should person A do, assuming their mental building blocks are static”. Therefore, a good first approach is probably to assume that the other person is truthful about their struggle with X and then try to think of strategies that assume their mental building blocks are static and design a solution around that. - Redundancy: If we assume that mental building blocks are more different than we intuitively expect that also means that the information we send should be more robust to other models. One way to create that robustness is to make the key parts of the message redundant, e.g. by explaining them with multiple different mechanisms, examples or analogies.

- Detail: Independent of your mental building blocks, there will be things we agree on. Those with worse building blocks for the task just take much longer to get there. For example, we can both agree on an answer in the shape-rotation game when we physically build the shape and rotate it. But some people can do it in their head while others can’t or take much longer. Therefore, if you realize that other people don’t have the same building block, you should start from details that you both agree on and then walk them through the same logic that you would perform intuitively. For example, in the shape-rotation game, you should start with a small rotation and give the other person time to verify that it is still the same shape.

Find your strengths

If there truly are big differences in our mental building blocks and it is hard to change them, it makes sense to find out what your mental building blocks are and what they are good for. I guess most people even know what they are good at or would at least be able to get a good first impression with a bit of introspection and feedback.

Most of your mental building blocks will be just about average but some of them will stand out positively or negatively. Often these come with a sense of “I’m just inexplicably bad at this” or “everyone else is just inexplicably bad at this”. For example, I found it a bit confusing why people don’t “just rotate the shape in their head” when they struggled with it. On the other hand, my guitar instructor or music teacher probably thought “Why doesn’t he just do the thing” when they tried to teach me music-related things.

I think this search for your own strengths is especially important when you think that impact is power-law distributed. In that case, the vast majority of impact comes from very few people who are very very good at a specific thing. Inversely, most of the people who are high achievers likely built their careers around the mental building blocks they are really good at.

Find other people’s strengths

When you work with others, e.g. as a manager, it is in your interest to find out the mental building blocks other people are really good at. Specialization increases the productivity of the entire group after all.

Some people might assume that this search for strengths happens automatically through education and other selection mechanisms but I would expect it to be much trickier. For example, people could end up somewhere due to lots of path dependencies. They think they have to continue on their current paths due to sunk cost but they might not realize that a switch is both more effective and more fulfilling when they notice that a different path is better suited.

Therefore, as a manager, one should probably put more time into finding people’s strengths (together with them) than is common.

Curse of knowledge

By studying a topic and educating yourself, you get new building blocks that were previously inaccessible to you. For example, when I think about matrix multiplication, I think about them as squares and rectangles and how they combine to form new geometric objects. This way of thinking has become so intuitive to me that when I look at the symbols on the screen or paper my head mostly thinks in squares and rectangles. This mental building block did not exist 10 years ago. I would have been able to understand some of it but it was not a core tool in my toolbox and it would have taken me much longer to think about.

Unfortunately, we tend to forget that other people don’t have these kinds of building blocks at their disposal (see curse of knowledge) and we often explain things as if the other person had already acquired our mental building block.

This effect is further exacerbated by a selection effect. Usually, the people who teach are the ones who find a topic naturally easy, i.e. those that already have a good mental building block for it. With these two effects combined, people tend to drastically overestimate how fast others can learn and how basic you have to start. Therefore,

- Start with the necessary concepts: The concept you are trying to explain usually relies on more fundamental basic concepts. Most of the time you have a clear understanding of what these necessary concepts are but your students might not. Therefore, I suggest explicitly stating what the necessary concepts are and spending some time explaining their most important details.

- Explain your own building blocks: I often found it very helpful when someone explained their building blocks on a very nuts and bolts level to me. Often that includes drawing simple sketches and using very simple language. The “this goes here, that corresponds to this, etc.”-kind of explanations with wild gesturing were often most useful to me. I think people often shy away from these very basic explanations because they remove the plausible deniability that you have when using vague and abstract concepts. You just need to regularly remind yourself that you actually care more about getting the model right than pretending to be correct.

Professors seem to universally fail in tutorials. Often they give some hand-wavy answers to the students’ basic questions because, in their mind, it’s just impossible that somebody could struggle with such an obvious problem and then go on to talk about “a few extra things” for the rest of the tutorial that nobody understands because they already got lost in the basics. To prevent being like that, you have to really force yourself to think slowly and explain all the basics. It will probably feel annoyingly slow and tedious but it will make the students very happy.

I have been a tutor for multiple university courses and my students always understood the most when I just slowly explained the basic stuff and poked holes in their current understanding. I guess the main obstacle as a tutor really just is to ignore your own mental building blocks and help the students build and refine theirs.

Conclusion

For some of you, everything I said might have been super obvious. For me, however, the realization that “other people literally don’t have access to the same tools as I do and vice versa” was quite helpful to improve my communication and interaction with others. I would also be interested in additional examples, so let me know if you can think of more.

If you want to get informed about new posts, you can follow me on Twitter.