What is this post about?

I have experienced the following situation multiple times “A friend of mine and I had a discussion where we disagreed on something. The discussion is not resolved at this point in time. Sometime later (maybe a couple of months or even years) we discuss the same issue again. Suddenly we both agree but claim not to have changed our opinions. I genuinely believe not to have changed my opinion and they genuinely claim to not have changed theirs.” Somewhere in this process, either of us has to have changed their opinions. I think this phenomenon is related to the human desire that their beliefs “follow a red line” over time i.e. we want our convictions to be consistent with each other and we don’t like to be wrong. Accepting that we have changed our minds implies “admitting” that we have been wrong in the past. Since we prefer the warm feeling of being right over the sad truth that we have been wrong our brain mostly pretends that we have always held the opinion that we currently hold (probably some combination of egocentric bias, choice-supportive bias and rosy retrospection). Obviously, my description is a simplification and this is not true in all cases and there exist exceptions. I believe that this fallacy has bad effects because it prevents us from learning from our mistakes effectively. I think we should, therefore, embrace the fact that we have been wrong in the past and are less wrong now. In this post, I list a couple of issues on which I changed my mind and discuss why I think that happened. I try to only take views on which I had an explicit opinion which I then updated and not just new things that I learned even though the border is somewhat vague. If you think that my current beliefs are inaccurate or wrong I would be happy to discuss them with you. When reading this text, keep in mind that I have not written these opinions down explicitly at earlier points so they are a reconstruction of my memory.

People

Importance of social relations

My opinion about the importance of the quantity and quality of social relations actually changed quite drastically over time. As a teenager, I was of the impression that it is very important to have many friends and be liked by everyone. After starting university I realized that I actually didn’t have strong reasons to keep most of my social relationships from school because of diverging interests. My new belief was that most friendships aren’t worth much since you lose them once you change location, job, etc. I have softened this view quite a bit to arrive at my current position where I think that it is important to have a core group of friends that you can trust and plan to keep in contact with even when you move location. I still believe that there is no reason to try and please everyone.

Polygamy/Polyamory

During my undergraduate I was very libertarian in my belief about sexual relationships (more in theory than in practice though). I thought that the most important thing in relationships was to be as free as possible, i.e. to do whatever you want with whomever you want as long as this partner consents. I saw every form of commitment as a restriction in my freedom and therefore rejected it. I now believe that commitment is an important and necessary thing for a relationship to work. I think I changed this view because I undervalued the benefits of long-term stable relationships. I kept my view on Polyamorie and still believe that people can have more than one relationship at a time.

Signalling

I always had the intuition that communication was not only about transmitting information but also signalling status, intentions, etc. I think I first realized this after going to the theater. After the play, I wanted to discuss the plot with some members of the group and its possible interpretations. Some of the people had not even listened very carefully or were playing around with their smartphones during the play. However, they were very keen on telling their friends and family that they have been to the theater. They wanted to signal that they are a very intellectual person and gain the social capital attached to it. I think this can also be seen on Facebook or Instagram. While some part of “sharing with your friends” is surely information based, i.e. you want them to know that you are on holidays, another part is used to signal that you are able to signal some positive attribute, i.e. that you are able to afford holidays, that you have a happy family, etc. Thinking about communication not only as transmitting information but also as a means to communicate status and intentions can tell you a lot about the person you are talking to. “Reading between the lines” and asking what kind of attributes they want to be associated with often tells you more about the person than what they are actually saying. My opinion on signalling has been influence strongly by reading “The Elephant in the Brain” and an episode of rationally speaking. I want to emphazise, that realizing that something is signalling does not make it worthless. This blog is to some extent signalling but I hope it still contains useful information.

I am less smart than I thought

During most of my school career I had a very easy time even with low effort. When I was ten years old I did an IQ test with my good friend Samuel. I did not really understand what the results meant, just that we were “pretty smart”. The social feedback that I received during most of my school career also was that either I was the smartest person in the room or that Samuel and I shared the top two spots when we did something together. This perception mixed with the hormonal cocktail of an 18-year-old made me overvalue my intelligence. I think I have come to the sad conclusion that I am less smart than I thought I was mostly due to the following reasons.

- Meeting a ton of people who are clearly smarter than I am. My social bubbles are Effective Altruism, Debating and Academia. All of those are (self-)selective for intelligent people and after meeting some professors, students, debaters or EAs there was just no way denying or rationalizing the huge gap in intelligence that exists between me and a more intelligent person. It was just obvious that they were smarter.

- A better understanding of probabilities. I think that the IQ test is a relatively accurate representation of someones intelligence. Of course there are some problems with the selection of questions discriminating against certain groups or some people preparing for the test and thereby feeling really smart and skewing the curve - but as a broad approximation it works. After having understood that the IQ number that you get is just a representation for the percentile in which you fall I knew that there were 100-X percent of society that have better results in the test than I do. (I retook the test when I was 20 and had the exact same result as when I was 10, that gives me more reason to believe it measures something reasonable)

- A better understanding of conditional probabilities. The IQ test tells you your intelligence in relation to the entire society, i.e. you are in the X-th percentile. However, most of the time our social circles are highly selective. After reading up on the average IQ that people in a Bachelors program, Masters program, PhD or Post-doc have, I had to accept that with high probability I will not only be not the smartest person in the room but in fact, might even be below the average IQ of that select group of people.

I undervalued experience

I originally thought that experience is overvalued and to solve a problem it would be best to argue from first principles and use intelligent reasoning. I though that a lot of experience was folk wisdom and would not actually stand up to scientific scrutiny. I still assumed that on average more experience would imply a higher proficiency within a certain field but I thought more experience could easily be outweighed by intelligence. So, for example, I would have assumed that an average intelligent person with 3000 hours of chess experience would easily be beaten by a significantly more intelligent person with 1000 hours of chess play. While I do not have any data on chess I would now estimate that these two people would either be equally good or the more experienced person would win more often. I think my opinion change due to a factor that can be summarized as the gut feeling. I originally thought that the majority of the knowledge we have about a certain subject was easily accessible and would be factored in during decision making. However, after finding out that many professional chess or Go player often base their decisions more on feeling rather than logic and many experts have problems justifying their predictions with logic even when they are correct, I had to update my model of decision making. I now think it is to a very large extent latent knowledge that controls our decision making. It is the combination of the thousands of situations that an expert has assessed before and the many times they have been wrong that lead them to have a more calibrated model of a situation. I was aware of the existence of the subconscious parts of our decision making and merely changed my opinion on how much of an influence they have. The practical consequence of this is pretty simple: I am now more likely to trust a person that has a lot of experience with the assessment of a situation even if they cannot explain it. Merely the fact that they “have a bad feeling about it” now has a lot of weight for my decision. I would now rather try to get to the bottom of what exactly produced this “bad feeling” rather than discarding it as “just a feeling” and searching for a more logical explanation via first principles. Often, the logical explanation is found after the source of the “bad feeling” is identified.

Rationality and emotions are not mutually exclusive

Until coming in contact with Effective Altruism and thereby the rationality community my views on rationality were mostly shaped by conventional norms and pop culture. I thought, for example, that Sheldon Cooper from the big bang theory was a rational person due to his cold and distant attitude. However, there are a lot of Sheldon’s characteristics and behaviors that are terribly irrational. For example, he is very reluctant to accept that someone else is correct even in the face of overwhelming evidence. It was this cultural representation that led me to believe that emotions and rationality are mutually exclusive and I strove to repress or ignore them. Now I think that there are two aspects to rationality. First, rationality implies that you search for the most effective ways to reach your goals. Second, rationality implies that you want to have the most accurate representation of reality, i.e. you want to remove biases that cloud your perception of the world or your decision making and you want to make informed decisions based on that knowledge. These definitions are not directly mutually exclusive to emotions. Some emotions might stop you from making decisions that maximize your goals and should, therefore, be accounted for. I believe, for example, that grief and jealousy are pretty useless emotions and try to make a conscious effort to overwrite them but other emotions might very well be an integral part of your decision. Happiness or love might even be the very goal you are trying to achieve with rational decision making. Unfortunately, the cultural wisdom of “rationality == no emotions” is very sticky and pernicious and it will take some time for it to vanish. I think it is actually pretty important to clear up this confusion because it leads to bad situations. Some people are mean to their partners in relationships under the guise of rationality because signaling that you are especially emotionless can be pretty hard for your partner (I was definitely guilty of that in the past). It also leads to some people rejecting important lessons from rationality (i.e. how biases cloud our decisions) because they think becoming more rational means giving up their emotions.

Update: There are some things I would like to clarify

- Sometimes emotions and rational decision making is orthogonal to each other. If I am angry with my partner and, therefore, desperately want to take revenge it will fulfill my emotional satisfaction but is irrational because it probably only causes more harm in the future. I mostly argue that there exist situations in which this mutual exclusivity does not have to be the case.

- Trying to overwrite your emotions is only one of multiple strategies that one could use. Introspection, e.g. questioning why you currently have a certain feeling and whether it is justified, should also be done since it yields valuable insight.

Debating has some downsides

While I think competitive debating has a lot of positive effects on you, there are also some downsides that start to annoy more the longer I debate. On the plus side, you learn a lot of analytical skills, your ability to communicate complicated information improves, you have stronger incentives to inform yourself about global issues and think about very fascinating ethical, political and scientific questions. However, there are a couple of issues that are inherent to debating. I assume that most real-life decisions are based partly on data and partly on intelligent reasoning, e.g. if you want to know whether buying a house is a good investment you would think about the benefits for you and your family but also look at the current and projected future price of this asset. Some decisions are more influenced by reasoning (some ethical debates maybe) and others are more influenced by data (who to choose as a party nominee). However, knowing facts and statistics (i.e. the data part) about the world is somewhat helpful in debates but by far not to the degree it would be in real life. Since you can’t assume the average intelligent voter to know the latest polling statistics or the average income of someone living in Mexico and debates don’t allow you to use the internet, every statement that you make about these numbers can be effectively countered by a counter assertion. “Trump has a 42% approval rating” can be negated with “That’s not true. Trump’s approval rating is 53%”. And in the context of debating this makes, to some extent, sense. We can’t validate whether a given statement is true or not so the teams must argue about its truth-value. But sometimes in debates, when someone just gave five shitty reasons for something to be true which clearly isn’t, I just think “Ah shut up and google it”. A less problematic but still potentially negative effect of debating is the attitude towards the truth that you can pick up over the years. Since debating is competitive you sometimes care more about winning an argument than making a true argument. And while these two should in theory be linked very strongly, in practice the accountability is not superb. After all, judges are not experts in most fields and they still have to judge your persuasion without too much prior knowledge. While this lax relationship with truth might not be much of a problem in some areas - in fact, you might be paid for exactly this attitude, it backfired during my first encounters with serious academia. While writing a paper I had a hypothesis that would confirm a decision that I had made w.r.t. my experimental setup. It wasn’t a very important decision and I didn’t want to waste too much time running experiments for it because there were more important experiments to be run. So I just wrote up some reasons for why this hypothesis was likely true and thought “well, there are some reasons so you should believe that”. Clearly, this isn’t how science works and was and am aware of that fact and corrected the part in my paper, referenced other work that had made the same decision and ran experiments. I just think it’s important to “ground yourself” from time to time and realize that being good at debating does not allow you to run around like you have figured it all out just because you can come up with more reasons for something. Especially experts in your field, while they might not have the same training in persuasion, will spot your bullshit very quickly and will not take you seriously in the future. If you don’t know the answer to something, don’t make up one and defend it but just say that you don’t know. However, as long as you remember that a debate in academia isn’t about winning but about getting to true results you should be fine. Even though I have analyzed the downsides of debating much more than the upsides I still believe the benefits outweigh the harms by a lot and it is one of the most useful hobbies one could have.

Ethics

My perspective on Effective Altruism (EA)

When I heard of EA for the first time I was immediately drawn into the movement. It just seemed so obvious to me: There are millions of people suffering right now and there are effective tools to help them. I immediately wanted to start and do something. The urge to act was enormous. Since I had just started my undergrad the only things that I could realistically do were organize meetings, go to conferences, focus on my studies, become vegan/vegetarian and donate parts of the little money I had. I was aware of the fact that these contributions didn’t matter that much, I couldn’t donate a lot, the local meet-up grew slower than I had hoped and one person being vegetarian or vegan only alleviates a very small amount of suffering. So my best shot was to focus on my studies, get into a good position to either have a lot of positive effects through my work, or donate a lot to effective charities. The fact that this seemed like the only reasonable shot at having a high impact really put a lot of pressure on me and every bad grade felt like I was stabbing a future child by not being able to donate as much. This is obviously neither healthy nor helpful. I thought about this pressure and as already described in my EA article I changed my perspective to preserve my mental health. The second way in which my view on EA changed is on the immediacy of help. I think this urge to help immediately when you see suffering is very strong and I therefore wanted to donate NOW or to rush through my studies to get a job ASAP. However, this strategy is not long-term optimal. EA is, historically speaking, still in its infancy and a lot of assessments might be updated quickly. Just take the shift in stance that 80K has made on earning to give. After my Bachelor’s I could have rushed to become a trader and donate most of my earnings only to find out that this was ineffective compared to working on some projects directly or be an AI safety researcher. I guess my view on career choice can now be summarized by the following ideas:

- Choose something that you are comfortable doing now but also will likely be comfortable doing in the future. Expertise builds up over time and being an expert in something you don’t enjoy anymore is probably suboptimal.

- If you don’t know what you want to do try around a lot. Go to EA conferences, speak to a lot of people, read 80K, etc.

- If you realize your current choice does not suit you don’t hesitate to switch even if it feels like “having wasted all that time”

- Do not optimize for immediate impact at the cost of larger long-term impacts. A high government position might be very impactful even if you “had no impact” until reaching that position

Short-term vs. long-term Effective Altruism

One of the EA internal debates is on a dimension of short-term vs. long-term effects. I would say I did not have a strong opinion on it in the beginning but was leaning slightly towards short-termism because of the urge to act now as described in the paragraph above, the high uncertainty attached to some of the long-term scenarios and a certain fear of failure (e.g. what if I became an AI safety expert but fail to contribute anything meaningful). By now my view is leaning much stronger towards the long-term end of the spectrum. This is partly because the community as a whole shifted their stance a bit, partly because I am less risk-averse now (and can, therefore, more easily accept to maximize expected value) but most importantly due to a talk given my Stefan Torges (see his blog) and a conversation following it. In the end it is a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation but was still able to convince me sufficiently to update my view pretty drastically. Let’s assume that the trajectory of human civilization is not yet near its end and will go on for 100k years at least. Further, assume that the sigmoidal shape of population growth is broadly correct and we stagnate at 10 billion humans on the planet. Let’s say there is a 1 percent chance of a global pandemic (like CoviD-19), a 0.1 percent chance of a world war, and a 1 percent chance of a very bad AGI scenario per year. This implies that in 100k years of civilization there will be 1k pandemics, 100 world wars, and 1k very bad AGI scenarios. Let’s further say that around half of the global population would be affected by the pandemic in a significant way and everyone by the world wars and the AGI scenario. If we assume that the suffering that is created through these scenarios is equivalent to the suffering of having malaria, then reducing the number of pandemics from 100 to 99 means that 5 billion people in the future do not have to suffer. That would on average be 50k people per year. Using GiveWells estimate of 6000 Dollars to save a life from Malaria we would be at 300 million dollars per year. That is an amount that I am very unlikely to earn or even come close to over the entirety of my life. The same estimates can be made for the world war scenarios, the bad AGI trajectory and other long-term problems such as climate change and yield similarly astronomical amounts of suffering. The chosen numbers are obviously guesstimates and might be very wrong, but even if they are wrong by a couple of magnitudes the argument is still pretty strong. Before Stefans talk I already knew that “the future is long, there are many people, large impact, blablabla”. I still needed to crunch the numbers to get an intuitive understanding of the incredible magntitude of these effects and thereby convince myself to such a degree that the felt uncertainty attached to the long-term perspective becomes pretty irrelevant.

Happiness/Suffering is not the only valid metric

I think there are two different Happiness related opinions I updated.

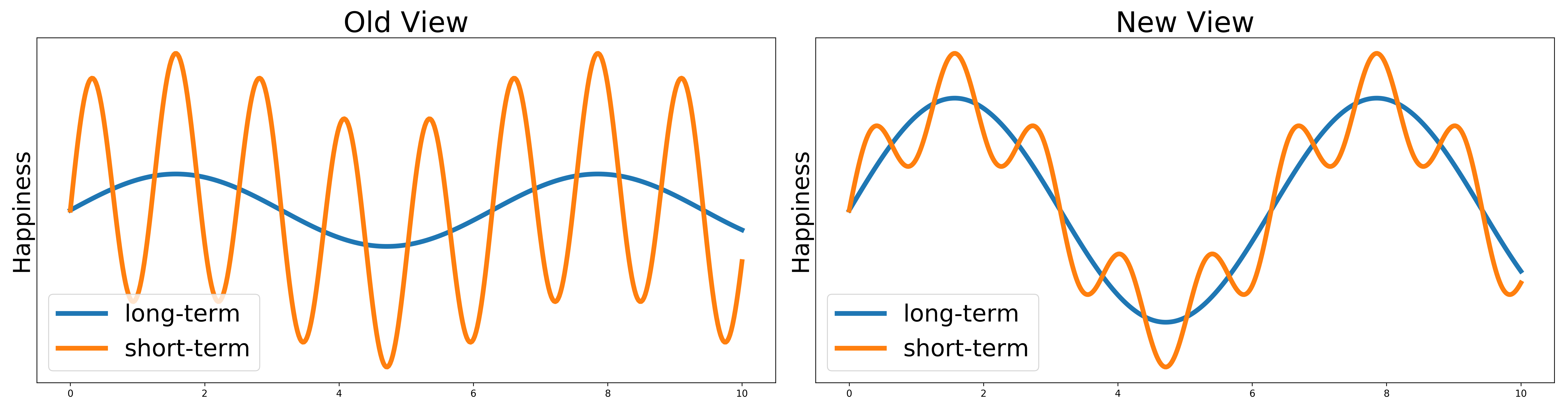

- Happiness includes much more than the short emotional ups and downs plus diseases. Some harder to measure mental states such as contempt/satisfaction/tranquility/depression must be factored in very strongly. I never denied the existence of the influence of these other factors I merely updated the degree to which I think they influence the overall happiness of an individual. While my original estimate was around 80:20 for short-term emotions it is not something like 70:30 in favor of other mental states. The reason for this update was mostly due to personal experiences. When I explicitly compare a good day in a rather depressive phase of my life to a bad day in a contempt phase of my life I prefer the latter. This is hard to explain with the original numbers. To illustrate consider the following figure.

- Non-happiness/suffering focused metrics have more validity for me now. I overall still think that a suffering focused ethic is probably correct. However, I changed my view on what kind of things are a good proxy for suffering. Agency, for example, seems like something that I would value higher now than some years ago because it has a higher influence on my well-being than I expected. Fairness is something that seems to affect the average happiness of a group more than I had expected as well. Are agency and fairness therefore inherently important values? I don’t know but also don’t care. As long as they lead to positive mental states it doesn’t matter to me whether we call that mental state “being free” or “being happy because we are free” (I guess one could have a long philosophical discussion about this).

Science

Science is less accurate than I thought

My pre-undergrad understanding of science was terribly naive. I assumed that scientists tested hypotheses by running experiments that then yield easily interpretable results which can then be seen as “truth”. What I completely underestimated was the complexity of the scientific apparatus, i.e. fact that science is conducted by people which have to follow certain rules that are made by people who are not necessarily scientists themselves, etc. There are some reasons that lead me to believe that science produced/produces a lot of results that are either overblown or just wrong.

- Incentives: In an optimal world a scientist’s sole incentive was to conduct research and report the results as accurately as possible. Unfortunately, we are not in that world. A scientist has to secure funding, wants to climb the academic ladder, and has personal goals. For all of these, it is important to publish and most scientific fields value positive results way higher than negative ones people found ways to bend the truth a bit. Bad incentives have led people to use practices such as p-hacking and thereby led to a replication crisis in many fields. Additionally, following the scientific debate in some fields, I have come to the conclusion that some researchers care more about their own status in the field than truth or the progress of their field. This includes situations in which scientists don’t retract research even though flaws have been shown or don’t stop proselytizing their personal theory even in the face of strong contrary evidence.

- Social dynamics: If you have been in academia yourself you will probably have witnessed some of the daily banter about one theory being better than another, e.g. Neural Networks vs. other forms of Machine Learning or Bayesian vs. Frequentist statistics. This banter can easily get out of hand and become a cult-like ideology like the Connectionist vs. Dual route debate in linguistics. These debates can become so heated that they decide the question between publishing or not publishing a paper, getting or not getting a position and receiving or not receiving a grant. While it is clear that scientists often have debates and constantly reject their own or someone else’s hypothesis this cult-like behavior is on another dimension. The fact that a scientific question, paper, or even entire career is not decided on merit but adherence to a cult is already a bad sign for science. Because of this the progress of the field is not determined by the hypotheses that explain the phenomena best but rather by which cult currently has most people in important positions. Clearly, most science is not that extreme, but some weaker form of this can be found in most fields. I guess the human desire to cluster everything into tribes is still stronger than we expect.

- Statistics: Statistics are a complicated business and many sciences don’t even teach the very basics to their students. Due to a bad understanding of statistics, monetary constraints, or time restrictions many studies use sample sizes that are so small that you effectively can’t trust the conclusions at all. The fact that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are only just becoming the norm in medicine also means that the validity of many past and current studies is questionable. However, lots of studies with a miserable methodology or small sample sizes make it into the mainstream through breakfast TV and other channels of questionable scientific accuracy as long as the message is sufficiently surprising. “A new study found that doing X increases the risk of cancer Y” is probably one of the most overused sentences on main stream TV but the statement is probably false as often as it is true.

- The world is complicated: Even if you do everything right - use an RCT, take the right sample size, look at other variables, etc. - the result might still be wrong on a larger scale. I think I just underestimated how hard good science actually is because there are soooooo many possible reasons for something to work like it does. Maybe it’s just a local trend, maybe it’s a third variable, maybe it’s the fact that you conduct an experiment and people act differently due to that instead of your treatment, etc. The list of things that you didn’t think about is very very long and there are many things that go different than you planned them. All of this means that even the most sophisticated setup does not necessarily capture the true effect. A light at the end of the tunnel is the rise of meta-studies, i.e. studies that accumulate the results of many different smaller studies and check whether the general trends hold when combined. This, however, means that robust science takes years and years and many hundreds or thousands of scientists to work well. Unfortunately, meta-studies don’t really tell you a lot if all underlying studies only report positive results.

- Third-party interests: Companies that want to sell you something that is bad for you don’t want you to believe it’s bad for you. Soft drink producers have funded alternative studies that show that the main driver of obesity is not sugar but fat for years. So whenever they are confronted with criticism they have plausible deniability and another theory that I can easily use to justify my bad drinking habits to myself. My monkey brain essentially just takes solace in the fact that “we are not really sure that soft drinks are bad for you, it could also be something else”. Similar tactics have been employed by the oil lobby and alternative climate science, the gun lobby and alternative statistics about gun-related incidents or the alcohol or meat lobby w.r.t. negative health effects. The list goes on and on and the fact that, no matter what you want to find out, there likely is an adversarial player trying to sell you some crap really does not make life easier.

Keep in mind that these effects don’t apply to all sciences to the same extent. In Chemistry and Physics you can measure the effects more precisely than in Psychology and it is therefore harder to fake results.

After all of this, I still love science. Even though it is a flawed tool, it is the best one we have. There are millions of people worldwide, trying to improve our common knowledge, help each other out, and enhance our current methods. My personal experience with science has been mostly positive and the people I have met were smart, open and helpful.

Machine Learning and AI is powerful in different ways than I thought

My original belief about Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning was mostly driven by pop-culture (such as Ex Machina or Her) and news reports about AlphaGo and similar achievements. So when I entered the field, I expected to work on android-like robots that perform human tasks or other agents that learn from their environment. I did not expect that ML was so data-driven and most algorithms were tested on tiny images of numbers, a task, that seemed so easy to me that it felt totally out of place. As always the more I learned, the more I had to accept that everything is more complicated than it seemed and we actually don’t know shit. By now, after having spent nearly 4 years in close proximity to the field my thinking about it has changed. Even though the results of DeepMind, OpenAI & Co in Reinforcement Learning (AlphaZero, AlphaStar, Dota2) or natural language processing (GPT-2) are cool it will likely still take years until these systems are readily available and their training does not require an entire farm of GPUs to run for a couple of weeks. However, there are lots of things that ML is already a lot better than human understanding. Especially when it comes to trends in large data sets humans seem to be unable to handle the complexity. My personal opinion is that we should prioritize making current methods more efficient and more robust instead of trying to go for the big shot and try to “solve intelligence”. But I can also see why other people might have different opinions and it is probably up to personal preferences.

Neuroscience & Psychology understand merely the basics of thinking if at all

The reason why I studied cognitive science was that after reading “Thinking Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman I really wanted to “understand” the brain and human thinking. I was as naive as the people who 70 years ago thought that natural language processing could be solved in three months by a couple of people. My expectation was that scientists had basically understood “how thinking works” and I merely had to read a bit and could then predict what other people think. My overconfidence came, to a large extent, from pop culture such as “Lie to Me” (it’s absolute trash and you should not watch it) which gives you the impression that psychology and neuroscience have figured it all out. When I started my undergrad I read the entirety of Neuroscience: exploring the brain and was baffled. The book contained “all the basics”, e.g. synapses, neurons, the visual cortex, spinal cord, an overview over some emotions like fear but “the real stuff” was nowhere to be found. Questions like “how are thoughts formed?” or “what area of the brain is used for lying?” were completely unanswered. Rather quickly I had to make the painful realization that there were way more questions than satisfactory answers and we actually don’t know much at all. Whenever we think we found all types of neurons somebody finds a new one. We have a broad idea of how vision and other senses work and some hypotheses about how some emotions work but it is far from good understanding. All higher cognitive processes don’t have good explanations either. We can simulate really tiny parts of the brain but it is completely impossible to scale them up and simulate any kind of thinking. The funny colorful images that are produced by brain scans contain some information but it is not at all possible to tell whether somebody is lying or what kind of personality and preferences they have. I just massively underestimated how complex the brain is. Even though there are remarkable achievements in Artificial Intelligence, no system so far has come even close to reproducing the energy-efficiency or the learning speed of the human brain. A complete understanding of even “simple systems” such as the visual pathways will probably still take many decades of research even though it seems so easy when you see it working every day.

Economy

I underappreciated markets

I undervalued the effectiveness of markets and the many possibilities it can be used to solve problems. Frankly, in many cases, I also didn’t understand markets sufficiently and therefore didn’t trust them. A lengthy explanation deserves its own post which I will make at some point in the future. However, the short version is this: There are some conditions that should be met for markets to work. If they are met, I think markets are likely the most accurate tool to make predictions, price things, or calibrate beliefs about the world. The conditions are

- Incentives: They are the most obvious - if people can’t make any money they probably won’t bother engaging in the market.

- No natural monopolies and access to many people: Natural monopolies can occur in situations where you either have very high entry cost, i.e. you need to invest hundreds of millions of dollars to build a railway network, or where the good that is being sold relies on a distribution network that exists only once. For example, when one company owns the railway network, the water pipes, or the telecommunication network of a country it does not make sense for a competitor to build a second network next to it. Therefore, you have no competition and the service will decline while the prices rise. I think this can be seen by how bad the results of the privatization of water have been for most countries. Additionally, there should be access to many people since the more people participate in a market, the more accurate is the price, prediction, etc.

- No infrastructure: I think infrastructure should be built and maintained by states most of the time. This is for the simple reason that the costs of infrastructure are local but the benefits are global. Building a new and larger road, for example, is a money drain most of the time. You need to service it properly, fix all the holes, etc. The benefits of the road, however, mostly come from the access that companies now have to faster transportation of goods and people, etc. This means that the profits of infrastructure are very indirect, namely the increasing economic value and the taxes that are generated by it. A single company has to make a profit directly from operating the road. This means they either have to take charges, which decreases the number of people using it and thereby its functionality or they don’t build the road in the first place because it is not profitable. A government, on the other hand, can take a loss for the road every single year and still make up for it due to the increase in tax revenue.

- Limited possibility to change the outcome: I think betting markets are generally a good tool to get accurate predictions about future events. A betting market for weather, for example, might yield more accurate predictions than choosing your favourite weather station. However, these ideas only work if the outcome cannot be tampered with. An interesting idea, for example, would be to have betting markets on the likelihood of re-offence for prisoners. There are lots of biases in the judicial system and a market could overcome those. However, someone who has bet a lot on a person re-offending might try to actively increase the probability for this event by attacking the person or mentally bullying them. The wheather on the other hand is harder to fuck around with.

In conclusion, I think that there are some parts of society that markets are ill-suited to solve problems, e.g. water, infrastructure, public transport and some parts of health care. However, markets can be used in more ways than they currently are in other parts of society, especially when it comes to predicting future events or CO2 reduction schemes like emissions trading.

FCC chairman Ajit Pai

This is a very niche topic but it is one of the examples where my first impression of someone turned out to be probably wrong.

My first encounter with the current (2020) FCC chairman Ajit Pai was through John Oliver’s second video about net neutrality. He was presented as a classic Trump-era chairman who is in the pockets of big industry players, doesn’t care about the average consumers and caters to the rich. However, Freakonomics Radio #406’, which was a lengthy discussion with Ajit Pai discussing his stances and policy goals, convinced me that this negative framing is likely not entirely accurate. While I don’t know how much of the things he said are actually true and how much of them are just talking points to improve his public perception the vast majority of his answers actually made me believe that he genuinely cares about the average American consumer. His approach seems to be very business-friendly and market-oriented but some of the older regulations sounded like pretty dumb ideas in light of the rapidly changing communications technology landscape.

Block-Chain technology

I originally didn’t take block-chain tech very seriously. For me it was kind of a meme, another cult that promised to change the world with some weird product that doesn’t do anything. The fact that the Bitcoin and Hodlgang people often could not be taken very seriously did not improve my image of crypto. However, after some discussion with friends and reading a bit about crypto my view has now changed to the following. (All of my takes should be seen with a bit of scepticism since I am not confident that I have fully understood the matter of blockchain technology.)

- Blockchain technology can be used in multiple ways to improve problems in the status quo. Since it is a decentralized system where all transactions are transparent it could probably cut out the middleman (i.e. big banks) for most international transactions and thereby decrease prices and increase utility for most average people. It could also be used to manage transactions between different artificial agents in the internet of things and an increasingly automated world.

- I am not too sure whether it is good as a currency. Since it is heavily used as a means of speculation I don’t think widespread adoption will happen, since most people value currency stability over potentially higher expected increases in net worth. Additionally, I am currently not aware that central banks and other financial institutions can regulate or control this currency in any way. Some people might see this as a plus but I generally think that monetary policies on average do more good than harm and some regulations are probably reasonable when it comes to money. For a more detailed but easy to understand analysis see this ECB paper.

- As far as I know the massive energy consumption related to Bitcoins can be fixed with other crypto-currencies such as Etherium and therefore does not seem inherent to the technology. Other problems can only be fixed with strong government intervention. Since crypto is decentralized and values anonymity it is naturally attractive for criminal organizations. Only if a government controls who has access to the wallet or can check the owners identity could this be reduced. However, as soon as governments will regulate crypto currencies it might stop wide spread adoption in the first place.

- There are some benefits of having a fully transparent currency which has government oversight. Tax evasion is likely a lot harder and tax collection a lot easier. Instead of having a huge bureaucratic apparatus managing taxes you could just calculate everyones profits and deduct the taxes accordingly in an automated fashion.

Overall, I think blockchain technology has some interesting ideas and would be eager to learn more about them. If you want to chat about them, just write me.

Update: I basically think that block-chains and especially crypto currency is not that useful in the grand scheme of things. Most of the problems that block-chains intend to solve can also be solved with alternative technologies that require less energy and have less other baggage. Crypto is a highly speculative asset and the shenanigans that are being done with it seem to do more harm than good. There are some people who understand what they are doing and have a strong ideological attachment to the ideals behind crypto but most people have no idea what they get themselves into. I have held this opinion since ~2021 but added this update only in late 2022 after the FTX collapse scandal. Also, for full clarity, I do own a small amount of different crypto-currencies not because I believe that it is the future but mostly because I believe in highly diversified portfolios.

The solution to housing is not rent-control

I originally thought about housing in the following way: In most places of the world, more people want to live in a city than there is available housing. Therefore, the cost of housing increase rather drastically. The cost of maintaining a house is likely static or increasing with a less rapid pace than the demand for housing. Therefore, the additional profit that is now gained by the home-owners does not translate to improvements in service since most companies want to make a profit and are happy about the additional, free money. Capping this free money with rent control seemed like a reasonable idea to me.

My opinion was mostly changed by Freakonomics Radio #373 about why rent control does not work. A broad summary of the podcast says that a) even though we are not entirely sure why, empirically speaking, rent control has not yielded the desired results or even worsened conditions for housing prices in the long term, b) When money is not a factor for landlords to decide who to rent to other proxies get more important (e.g. culture or skin color as a proxy for socioeconomic status) and thereby hurt minorities more than in the alternative, and c) there are other options to solve housing issues more effectively. These alternative include but are not limited to

- Letting people build new houses. This can be accelerated by aggressively slashing housing regulations (e.g. how high you can build or which styles can be used), declaring more federal land for housing and build public transport to make the outer parts of town more accessible.

- Especially high-priced luxury appartments are often not rented out but rather used solely to speculate. Appearantly, the increase in value for these properties is so high that the landlords don’t bother taking the 5k dollars or more per month that, for example, an inner-city appartment in New York would give them. The only solution for this is to force them to rent out the appartments and decrease the price until someone is willing to move in. It’s actually weird that you have to force people to take a free 60k per year.

- Public housing actually seems to work quite well in reducing prices. The city of Vienna which is ranked number 1 on most global city comparisons has clearly done a lot of things correctly. These range from good public transport to a wide variety of cultural attractions. But, importantly, the city still owns most of the houses. 62% of the population lives in public housing and the rents are incredibly low compared to cities with similar quality of life around the world. Housing might just be one of the issues where the incentives of companies and the public interest are not aligned, but maybe there are also good market solutions that don’t intervene as heavily.

Invest money in ETFs

There are lots of different ways to invest the money that you currently don’t urgently need for a living. I was/am looking for ways to invest that money in a way that does not require me to be an absolute expert in the particular field but still yield returns that are larger than inflation. Having the money in a bank account is terrible because most interest rates are lower than inflation these days. I originally thought that investing that money into houses would be reasonable but I have now shifted away from this entirely because

- It’s a huge investment. You can’t just buy a small part of a house if you are just a student playing around with their money. Even if you are able to earn enough to own a house it’s a very illiquid investment, i.e. you can’t just sell it if you need some money urgently.

- The money doesn’t create the same value. Buying a house means buying a piece of dirt and betting that more people in the future would want to own the same piece of dirt. Investing the same money in the stock market means that other people can create value for society by producing something that other people want. Investing in a house and renting it out creates value for the living in it but I would intuitively say that it is not as much value as in by investing in the stock market. It was then clear that I don’t want to invest in housing or similar things, e.g. land or forest but rather buy some stocks. They are easy to buy and sell in small chunks and they create value in some way or another. However, there are tons of analysts in Wallstreet and London that spend all day looking at the latest trends and numbers, so I can likely not outcompete them. What I can do, however, is invest in ETFs. They are diversivied, require no middleman, yield good annual returns, and don’t require strong prior knowledge about the market. You can specify some restrictions if you want to, e.g. invest in emerging markets, the tech-sector or sustainable energy, and thereby broadly represent your preferences. If you think this reasoning makes sense and want to invest some spare money, tell me beforehand since there are always some schemes through which both of us can get some free money if I sign you up. If you think my reasoning is wrong, also write me.

One last note

If you want to get informed about new posts you can subscribe to my mailing list or follow me on Twitter.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.