Introduction

This post is written by Marius Hobbhahn and Dominik Hermle. Both authors have contributed equally.

Chronic pain is one of the major causes of suffering within medicine. Its prevalence has been steadily increasing in recent years and it has caused millions of patients great pain, emotional distress and functional disability. What makes chronic pain so special is that a symptom develops into a disease. Normally pain highlights a functional impairment or damage of organ tissue. In chronic pain, however, this is different. Through molecular processes, neuronal restructuring, and cognitive and behavioral mechanisms pain persists even after when the physical condition is healed. In contrast to other less painful diseases (e.g. diabetes, wheelchair, prosthetic limb) patients don’t seem to get used to their condition. Once developed chronic pain is constantly present for a long, potentially lifelong, period of time. It can range from mild pain (e.g. tickling sensations on feet and hands) to conditions that are rated a 10/10 on the pain scale, such as (e.g. cluster headaches and trigeminal neuralgia). Given that chronic pain creates a lot of suffering and its prevalence is rising, we think it’s worth asking whether it should be a cause area for Effective Altruists.

In the following, we will try to give a more precise overview of what chronic pain is, whether it correlates with specific demographic factors such as age, regionality, fitness, income, etc., and lastly discuss whether it could be a worthy cause area. If you think we have made mistakes in our analysis or ignored important facts, don’t hesitate to contact us. Even though one of us studies medicine we want to stress that we are not experts in the field of chronic pain.

We are not the first to address the issue of (chronic) pain within the EA community. The Organisation for the prevention of intense suffering (OPIS), for example, makes a strong case for more access to medication for pain relief and effective treatment of very pain-intense diseases such as cluster headaches. Our research is supposed to be complementary to their mission and it is possible that OPIS has already compiled similar resources internally. There are two other EA forum posts on specific interventions on pain medication for developing countries and cluster headaches. However, to our knowledge, a high-level evaluation of chronic pain (CP) as a cause area is not yet publicly available.

Summary of the results

We could not reach a general conclusion on whether CP should be a cause area because the field is too large and heterogeneous. However, we think there are certain interventions within the field of CP that hold promise. They are a) providing treatment to people who have conditions associated with immense pain (10/10 on the pain scale), b) providing access to pain reduction for poor people, especially in areas with bad health care infrastructure such as townships and favelas, and c) high-risk high-reward foundational research to understand the neurological drivers for CP. Thus we reach similar conclusions as OPIS and the two forum posts.

What is chronic pain?

There are two different ways to define chronic pain. The first is determined simply by the duration of pain, which can be either 3, 6, or 12 months depending on the part of the body involved, type of pain or medical handbook you’re reading. Secondly, CP can be defined as “pain that extends beyond the expected period of healing” and usually occurs when an injury is not physically present anymore, yet people still experience pain.

Pain, in general, can be divided into nociceptive pain or neuropathic pain. Nociceptive pain is caused by inflamed or damaged tissue activating specialized pain sensors called nociceptors. It is also the pain we know best e.g. after cutting ourselves with a kitchen knife. If activated by heat, mechanical pressure, acid and inflammatory molecules (bradykinine, histamine) nociceptors transmit a neural signal to the central nervous system via specific fibres. Neuropathic pain is caused by damage to a nervous fibre directly without activation of a nociceptor. It is less well understood and causes a rather different, burning sensation.

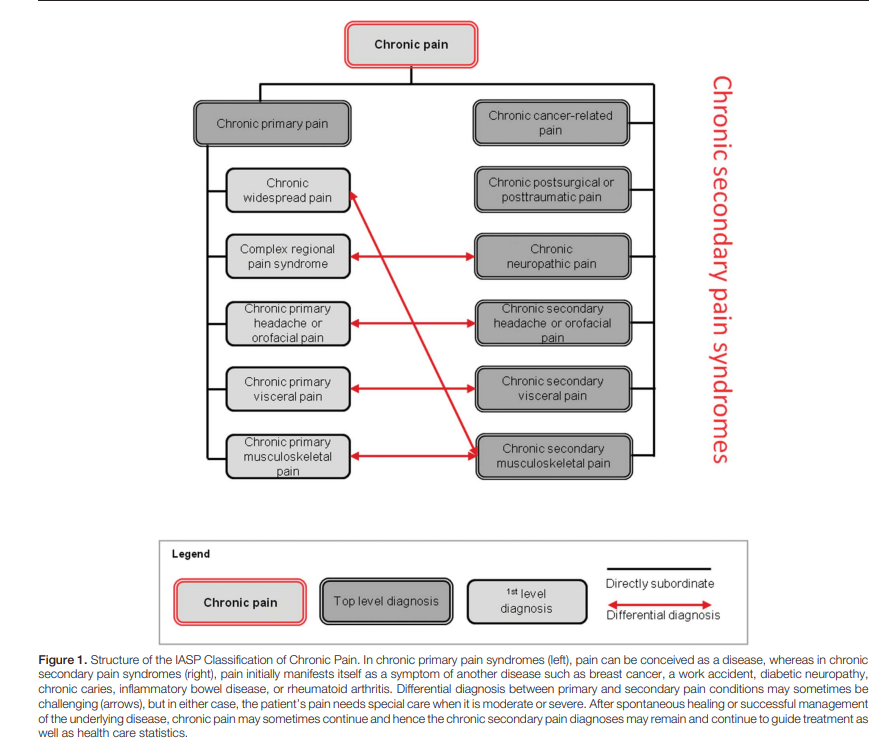

In medical diagnostics, CP is further classified according to its causes. An updated and uniform definition is given in the new version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-11, [11]). It differentiates between primary and secondary CP, both of which need to i) occur for at least 3 months and ii) cause significant distress and disability. Secondary CP is caused by some other known medical condition or due to a surgical or traumatic event (cancer, diabetic neuropathy). It can thus be regarded as a symptom of an underlying disease. Primary CP cannot be reduced to a different condition and is a disease on its own. Examples include some well-known conditions (chronic migraine, fibromyalgia, non-specific low-back pain), as well as many lesser-known ones (trigeminal neuralgia, cluster headache, complex regionary pain syndrome). Figure 1 in the appendix shows a broader overview.

Understanding Chronic pain is one thing, treating it is another. Since it is a relevant part of addressing the issues at hand, we would also like to give a brief overview of the treatment options in the status quo. There are broadly 3 directions.

- Pain-relieving medication through analgetics, most prominently represented by opioids. Though Opioids have a high short-term efficacy in reducing pain, they are difficult to use for long-term therapy. The main reason here is side effects (constipation, nausea) which increase with higher dosage to account for general tolerance effects.

- Interventional pain management. Some like Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) or spinal cord surgery have been shown to be quite promising in ensuring long-term pain relief. However, surgery in the nervous system carries the risk of significant complications and always requires a high-tech specialist setting which is difficult to scale. Thus they are used very selectively.

- Various accompanying therapies that address the psychosocial component of pain like psycho- or physiotherapy. They seek to maintain the patient’s functional ability, improve their emotional coping strategies and avoid dysfunctional spirals of social retreat and depression.

Demographics of chronic pain

Individual studies are generally helpful but can be selective or confounded. Whenever possible, we, therefore, try to base our evidence on meta-studies such as K. Mansfield et al. 2016 [1] which reviewed 127 studies on pain published between 1990 and 2015 and tested the influence of age, gender, and region. Fortunately, there are multiple high-quality meta-studies on CP.

Time

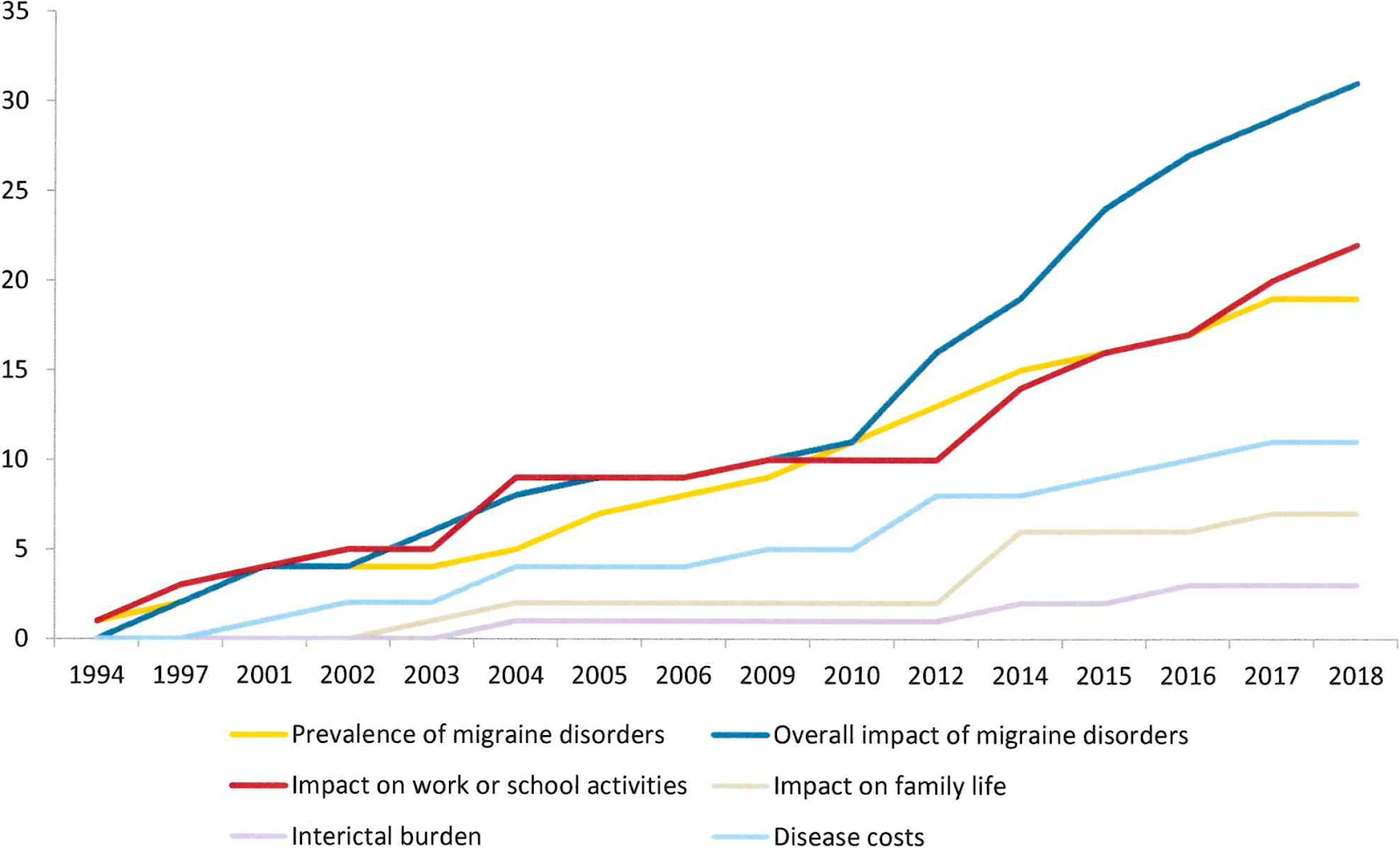

Most CP-related conditions have seen increasing prevalence over the last 20-30 years. Unfortunately, we didn’t find any meta-studies investigating CP timelines in their entirety and thus have to base our beliefs on studies of selective conditions. A study on Italy’s health performance between 1990 and 2017 [2] shows that low back pain, one of the most typical embodiments of CP, is the second highest contributor to DALYs in 2017 (third highest in 1990) and has risen by 11.2 percentage points (5.0% to 17.2% Confidence Interval) in that period. A meta-study on migraine [3] from 2019 showed that the prevalence of migraine has risen over time (see figure below). Unfortunately, the y-axis is not specified and we can thus not specify the exact rate of change.

A 2015 meta-study [4] compared the prevalence of chronic lower back pain in North Carolina in 1992 and 2006 and found a rise from 3.9% (95% CI:3.4–4.4) in 1992 to 10.2% (95% CI:9.3–11.0) in 2006. None of these results warrant to conclude that there is a global rising trend of CP but they all provide evidence indicating an increase in selective areas. This general trend would be plausible if possible underlying factors (e.g. Aging population, lack of exercise, etc.) are increasing as well.

Age

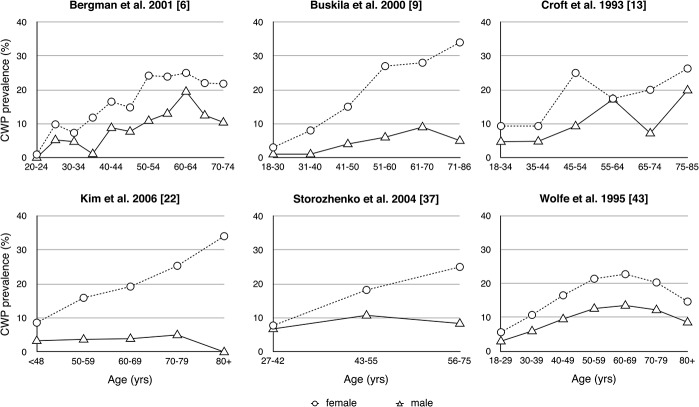

The prevalence of chronic widespread pain (CWP) is positively correlated with age until a peak is reached at around 60 after which it is anti-correlated. The meta-study of Mansfield et al 2016 [1] shows selected studies that report age as a variable (see figure). Third variables that could (partially) explain these results, e.g. work, obesity, or exercise were not explored and are potential confounders. However, the differences can also stem from methodological choices, such as different binnings of age or treating age as a binary variable, e.g. everyone >30 is old and everyone <=30 is young.

Gender

A result that we didn’t expect is that gender accounts for one of the largest, perhaps the largest, difference within a variable. A meta-study by Andrews et al. [5] found that the 95% confidence interval for the prevalence of CP was 5.5% - 8.9% for men and 8.3% - 14.2% for women. Mansfield et al. [1] found that depending on the study the female to male ratio for the prevalence of CP was between 1.06 and 4.80, i.e. in one study the prevalence for women (19.2%) was 4.80 times as high as for men (4%). The exact reasons for this are uncertain and different hypotheses have been formed. One is that biological differences between men and women explain the discrepancy in CP, i.e. women could experience more pain due to conditions such as dysmenorrhea, vulvodynia, or labor pain. A second hypothesis comes from psychological or social differences. Stereotypes about men state that admitting pain shows weakness and thus men might be more inclined to under-report. Women, on the contrary, are stereotypically encouraged to talk about their feelings and their pain. Thus, they might report more accurately (for further discussion and references see section 4.2 in [5] or [7], [8], [9]).

Region

We originally expected CP to be especially prevalent in the developed world since the population there is on average older, more obese, and more likely to work a desk job. Yet, the evidence is inconclusive and there seems to be highly variable regarding the prevalence of CP between developing nations. The meta-study by Andrews et al. [5] found that there is a significant difference between developed and developing nations regarding the prevalence of CP. More specifically, they find a CI of 6.9–10.3% for developed and 3.9–25.1% for developing nations. It must be noted though that their data was very sparse for developing nations and should be treated with caution. Another meta-study [6] focused exclusively on developing countries in South America, Africa and Asia. They found that there was a high variance between different developing nations ranging from a prevalence between 13% and 51% (One estimate for Nepal, see [24)]. After accounting for publication bias they estimated that the overall prevalence of CP in developing countries is around 18% which they compare to a mean estimate of 18.4% for Germany [27], 21.5% in Hong Kong [28], and 19-21.4% in the USA [29]. While the mean estimates show only small differences, it hides the underlying distribution of cases and countries.

| Country | Participants | CP prevalence (95% CI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil (Sao Paulo) | 826 | 0.42 (0.39, 0.45) | Cabral et al. 2014 [15] |

| Brazil (Salvador) | 2297 | 0.41 (0.39, 0.43) | Sa et al. 2008 [16] |

| China (Chongqing) | 1003 | 0.26 (0.23, 0.29) | Jackson et al. 2014 [17] |

| India (8 Cities) | 5004 | 0.13 (0.12, 0.14) | Dureja et al. 2013 [18] |

| Brazil (Sao Paulo) | 2446 | 0.29 (0.27, 0.31) | Ferreira et al. 2017 [19] |

| Iran | 1593 | 0.39 (0.37, 0.41) | Zarei et al. 2012 [20] |

| South Africa (Township in Mhatha) | 473 | 0.32 (0.28, 0.37) | Igumbor et al. 2011 21] |

| Brazil (São Luís) | 1957 | 0.42 (0.40, 0.45) | Vieira et al 2012 [22] |

| Lybia | 1212 | 0.20 (0.17, 0.22) | Elzahaf et al. 2016 [23] |

| Brazil | 723 | 0.38 (0.35, 0.42) | Souza et al. 2017 [24] |

| Nepal | 1730 | 0.51 (0.49, 0.53) | Bhattarai et al. 2007 [25] |

| Philippines | 11000 | 0.14 (0.13, 0.14) | Lu and Havier 2011 [26] |

| Random-effects model after controlling for publication bias | 0.18 (0.10, 0.26) | Figure 5 in [6] |

While the two large studies in India and the Philippines seem to have found a low prevalence of CP in their specific settings, there are other studies showing higher prevalence in parts of Nepal, Brazil, Iran, Salvador, and South Africa. To our understanding, there is no obvious causal mechanism distinguishing these countries that would explain such a large gap in CP prevalence and further research would be important to understand this large discrepancy. For our purposes, however, we can note that there are developing nations with a high prevalence of CP.

Misc. Factors

Besides the previously discussed conditions, the following were named as statistically significant covariates of CP in individual studies: Obesity, Smoking, Alcohol consumption, educational level, income, and type of employment ([20], [24]). Nevertheless, none of these were included in meta-studies and the results, even though they seem intuitive, should be treated with caution.

Uncertainty

The presented results should be treated carefully for two reasons. First, even though meta-studies control for different definitions of CP, e.g. whether pain becomes chronic after 3, 6 or 12 months, they can only mitigate the imprecision and not recreate the true conditions. Since different studies use different methodologies and definitions, two studies on the same population could yield vastly different outcomes. Secondly, CP correlates with a lot of other attributes and it is very hard to disentangle their causal relation. CP, for example, has high comorbidity with mental health problems (35% of CP patients also have depression, [10]). But it is unknown whether the mental health problems are a result or a cause of CP, or whether both are results of a third condition, e.g. a traumatic life event such as sudden unemployment.

Should Chronic Pain be a Cause Area?

From a high-level perspective, there are two strategies one could pursue in order to reduce the problems of CP. Either one can attempt to solve the root causes or attempt to reduce the pain through efficient pain treatment.

Scale

We estimate the scale to be medium or large. The prevalence of CP is somewhere between 5 and 50 percent of the population depending on the region and subgroup. This is more than most other health conditions though it can partly be explained by CP being a superset for different kinds of pain. The effects on one individual range from constantly annoying to very devastating pain (e.g. a nearly constant 10/10 on the pain scale). Especially in developing or emerging countries the prevalence and intensity of CP is high among the poor and uneducated ([21], [20], [15], [15], [16], [24]). The alleviation or mitigation of that pain would, with high probability, be a major life improvement for them.

Neglectedness

Chronic pain is still somewhat neglected in OECD countries but does benefit from growing awareness and funding in the last decades. While still being far from satisfying, therapy quality and options have made considerable progress. However, there still seems to be structural neglectedness in academic and professional medicine. This is illustrated by the lack of specialists, organizational capital (departments, funds) and its absence in many university curricula. Economically this market seems profitable due to a great number of Western patients with tremendous motivation. The lack of big leaps in treatment technology is therefore probably caused by factors other than market incentives. For developing countries, CP seems more strongly neglected, as prevalence is very high and means are very constrained. Unfortunately, this area is undercovered in media and science which makes exact evaluations hard.

Solvability

Chronic pain seems difficult to solve as it is biologically complex and not yet well understood. While many neural and molecular mechanisms of pain are increasingly better understood, we still lack knowledge about the process of chronification (ie. why does the pain continue to exist, even after regular healing?). In addition, there is often a huge gap between basic research and clinical application [14]. This has several reasons:

- Current animal models are quite unrepresentative of the actual clinical condition. This is due to a) the subjective component of pain which is difficult to measure in animals in a manner that allows comparison to human patients (ie you cannot hand out a questionnaire with a numeric ranking scale of pain) and b) the lab conditions not reproducing the multidimensional causes of CP (e.g. not including mental health comorbidities and social factors).

- A lack of robust biomarkers. As self-reporting tends to be quite noisy (e.g. confounded by daily mood), more objective measures would be helpful in improving the statistical and explanatory power of studies as well as cutting their cost. The latter is especially relevant concerning the incentives of the pharmaceutical industry. A promising approach would be to combine molecular markers of nociception and imaging markers obtained by fMRI and PET.

- Clinical research protocols often suffer from oversanitization of cohorts which makes the results less useful for wider clinical application. New study paradigms like population-based data collection without strict inclusion criteria could gain additional information for currently underresearched groups of patients by data mining.

The current trend in academic medicine views CP as multifactorial (= caused and upheld by biological, psychological and social mechanisms). This complicates the matter further, as research from different fields has to be integrated in order to design a multidisciplinary treatment approach. The latter includes interventions like psychotherapy, psychopharmacology and social work. Thus the underlying causes seem to be very hard to solve. Potentially, treatments of symptoms are easier to address. We would estimate that the biggest low-hanging fruits are improving access to pain treatments for the very poor and research on rare but maximally painful conditions as both seem to be currently neglected. A third option is basic research on the molecular and system-level mechanisms of chronification. Fourthly, a lot of maybe slightly boring but important translational groundwork can be done as we have outlined above, e.g. improving mouse models by the inclusion of depression and anxiety. Finally, there are high-risk high-reward interventions like DBS which can ensure long-term pain relief in up to 50% of (selected) cases [13]. Here there appears to be a promising impact, e.g. by facilitating surgical application and regulatory approval in a broader set of conditions and patients.

Conclusion

Chronic pain is a problem that affects many people and its effect can range from mild to unbearable pain. Thus we think that there are promising paths to reduce pain within the field of CP but since CP is an umbrella term for many different conditions we cannot make a recommendation for the entire field. Rather, we think that there are certain low-hanging fruits that have the potential for high cost-effectiveness. These include a) providing treatment to people who have conditions associated with immense pain (10/10 on the pain scale), b) providing access to pain reduction for poor people, especially in areas with bad health care infrastructure such as townships and favelas, and c) high-risk high-reward foundational research to understand the neurological drivers for CP.

Appendix

Overview figure taken from [11].

References

- Kathryn E. Mansfield, Julius Sim, Joanne L. Jordan, and Kelvin P. Jordanb; A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic widespread pain in the general population; 2016;

- Many authors; Italy’s health performance, 1990–2017: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; 2019

- Matilde Leonardi, Alberto Raggi; A narrative review on the burden of migraine: when the burden is the impact on people’s life; 2019

- Janet K. Freburger et al.; The Rising Prevalence of Chronic Low Back Pain; 2015

- P. Andrews, M. Steultjens, J. Riskowski; Chronic widespread pain prevalence in the general population: A systematic review; 2017

- Sá, Katia Nunes et al.; Prevalence of chronic pain in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis; 2019

- Roger B. Fillingim et al.Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings; 2009

- E. J. Bartley and R. B. Fillingim; Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings; 2013

- Stefano Pieretti et al.; Gender differences in pain and its relief; 2016

- Lisa Renee Miller, Annmarie Cano; Comorbid Chronic Pain and Depression: Who Is at Risk?; 2009

- Rolf-Detlef Treede et al.; Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11); 2019

- Nicholas Hylands-White, Rui V Duarte, Jon H Raphael; An overview of treatment approaches for chronic pain management; 2016

- Richard G. Bittar et al.; Deep brain stimulation for pain relief: A meta-analysis; 2005

- Jianren Mao; CURRENT CHALLENGES IN TRANSLATIONAL PAIN RESEARCH; 2013

- Cabral et al.; Chronic pain prevalence and associated factors in a segment of the population of São Paulo City; 2014

- Sá et al.; Chronic pain and gender in Salvador population, Brazil; 2008

- Jackson et al.; Prevalence and correlates of chronic pain in a random population study of adults in Chongqing, China; 2014

- Dureja et al.; Prevalence of chronic pain, impact on daily life, and treatment practices in India; 2013

- Ferreira et al.; Prevalence of chronic pain in a metropolitan area of a developing country: a population-based study ; 2017

- Zarei et al.; Chronic Pain and Its Determinants: A Population-based Study in Southern Iran; 2012

- Igumbor et al.; Chronic pain in the community: a survey in a township in Mthatha, Eastern Cape, South Africa; 2011

- Vieira et al.; Chronic pain, associated factors, and impact on daily life: are there differences between the sexes?; 2012

- Elzahaf et al.; The epidemiology of chronic pain in Libya: a cross-sectional telephone survey; 2016

- Souza et al.; Prevalence of Chronic Pain, Treatments, Perception, and Interference on Life Activities: Brazilian Population-Based Survey; 2017

- Bhattarai et al.; Chronic pain and cost: an epidemiological study in the communities of Sunsari district of Nepal; 2008

- Lu and Havier; Prevalence and Treatment of Chronic Pain in the Philippines; 2012

- Stefan Hensler et al.; Chronic pain in German general practice, 2009

- Wing S. Wong, Richard Fielding; Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain in the general population of Hong Kong; 2010

- Catherine B Johannes et al.; The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey; 2010

One last note

If you want to get informed about new posts you can subscribe to my mailing list or follow me on Twitter.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.